What is Contemporary?

By Tim Kennedy

In August I traveled to Chicago to see shows at the Museum of Contemporary Art and the Art Institute. Recently when I visit these institutions I sometimes feel as if I am a citizen of one of those contested provinces such as Alsace, or a small state in the Balkans, or perhaps I am even a member of a minority population dissolved and diluted within a larger population. Will my artistic passport be recognized? Will my history and experience be acknowledged and valued? Will my attempts to speak and understand the local language be understood? Will my vote be counted? Am I a citizen at all?

As an institution that represents the idea driven aesthetic, Chicago’s Museum of Contemporary Art has my respect; I actually prefer it to The New Museum in New York – perhaps because the MCA seems to recognize and present a cohesive history of its point of view. It has a collection of its own that it is committed to and periodically mounts logical and complete shows from. Plus it supports Chicago based artists. Among the shows I saw on this trip to the MCA was a show of photography from their collection titled Think First, Shoot Later, an excellent show devoted to the alternative comics artist Daniel Clowes, Homebodies, a show revolving around a deconstructed idea of domesticity, and a show by the Chicago based artist Theaster Gates.

The idea driven aesthetic is not what I am naturally drawn to, but if it is presented well it becomes an experience that I can take on its own terms. It is rare in this context for the visual to exist for its own sake – if a particularly visual work is presented you must contend with the distinct possibility that this aspect of the work is a feint. A matrix of ideas from critical theory surrounds and permeates most if not all of the work presented in spaces such as the MCA. The quality more often than not does not reside in the individual works but rather in the context that the work is placed in, both in the actual exhibition space and the space created by its place in the art world. The piece that completes itself solely through what can be gleaned visually is rare. Missing information needed to really experience a work may be available in the form of wall text or a setup essay. My best days in spaces like the MCA are if my time is open ended enough to let materials like these wash over me. Work that survives best and thrives in this atmosphere communicates its message quickly and frequently without a lot of nuance. I can have a variety of reactions to the kunsthalle type space that the MCA represents. Some days I can find it alienating and oppressive. On other occasions I find the shows stimulating enough to get my mind working in unanticipated directions and on really good days the experience makes me look at the world in a new way.

Still, it is difficult for me to consider myself a full-fledged citizen of the kunsthalle world – I will probably always be the immigrant from another country. Like any immigrant, I bring my own baggage and view things through my own lens. I am very interested in questions of “how”, for instance. How does the artist create the work, use the materials from which the work is made and ultimately manage our experience. The Contemporary sensibility moves away from media that stress areas of competence in favor of blurred categories. I must admit that I prefer a model of professionalism where we might encounter actual painters, photographers and sculptors. If I am denied this I suppose I try to turn what I encounter into the thing that I am seeking.

This was my experience in the Homebodies show at the MCA. Two familiar tropes of the kunsthalle world are to make the familiar foreign and to highlight the menacing implications beneath otherwise comforting institutions in society that we are all familiar with. This is the case with Homebodies, which examines domestic life through a feminist lens. Many of the major players from this genre are included in this show, but the piece that I responded to the most was one of Tony Oursler’s. It consisted of the egglike form that Oursler traditionally projects his video loops of faces onto and a suspended mattress, the corner of which is resting on and pinning down the “egg” or “head”. A crumpled flannel nightgown fans out from the head. The face projected onto the egglike form is that of a woman. In the inimitable Tony Oursler style her face contorts into a series of grimaces further distorted by the form of the egg as she vocalizes in an accusatory stage whisper variations of “I saw what you did!”. What did we (I) do? Is the head alluding to some illicit activity, perhaps even sexual abuse? Is it a false accusation or has the accuser hit her mark? In either case panic, anxiety and shame in the viewer kick in almost automatically. That this reaction is provoked makes it a successful piece on the level of subject matter and in the context of the show.

What I take away from the Oursler piece is a little different – the transformation of such simple and inert materials for me borders on the magical. It is uncanny. If you spend some time with a Tony Oursler piece you can almost convince yourself that you are in the presence of a living being, which is simultaneously pleasurable and disturbing. Part of the power of the transformation that takes place is due to the simple, low-tech aspect of the vehicle. I am taking pleasure in Tony Oursler’s competence as an artist. In other words, I am having an aesthetic reaction to his work.

I responded to the Theaster Gates show at the MCA in similar ways for slightly different reasons. The Gates show is a partial reprise of his installation at Huguenot House in Kassel, Germany for Documneta 13. The materials for both shows originated from Gates’ ongoing project to renovate a living and work space for himself and to create a cultural center in his South Side Chicago neighborhood. The show consists of several constructed objects on the second floor and objects and an installation with objects arranged around two video presentations on the fourth floor. Knowing some of the origins of the materials, the objects, the installation and the video give the work something of a halo effect. I am sure that the curators would argue that the real subject of the work is the social network that Gates is weaving – and this is an appealing aspect of Gates’s work. Part of what the viewer absorbs is the active imagining of the relationship of the work to the neighborhood and the community where it was spawned.

But again, what I am responding to are the qualities that are manifest in the physical aspects of the work. I confess that I didn’t spend a lot of time looking at the videos – one of which was a musical performance. I admire the way Gates orchestrates disparate and cast off materials and then arranges and recombines them. Gates pays careful attention to craftsmanship, which helps me focus my attention and makes me acutely aware of my surroundings – a set of beautiful stools constructed from detritus formed a semi circle around one of the video viewing areas. An illuminated display box constructed from plexiglass with an interior made from pieces of wood painted white and carefully fitted together resembles a construction from Schwitters. Upon closer examination a pristine white on white composition reveals itself to be pieces of lightly stained and soiled shag carpet. The aura they emanate is the sadness of passing time and absent lives – framed by a very aware, intelligent and sensitive artist. These are all objects, incidentally, that are presented to us in a half lit room in a casual offhand manner (this is part of the kunsthalle aesthetic too). Maybe this is fitting – can we really imagine the sculptural pieces presented to us directly in the manner of a David Smith?

I am a painter and, truth be told, what interests me most is painting. The real reason for my trip to Chicago was to see Impressionism, Fashion and Modernity at the Art Institute. It is a popular and well-attended show – clearly there is continued interest in painting and more specifically representations of the world. The hook with this particular exhibition was to display the paintings against fashion from the period – in some cases showing a specific garment that the artist used as a model. This has been a strategy on the part of Museums for some time to heighten interest and attendance. The best version of this type of show I have seen was Degas and the Dance at the Detroit Institute several years ago. As a painter it is interesting for me to see the actual things that the artists worked from.

To my eye the hit of the show was Manet’s Lady with Fans, his portrait of Nina de Callias from 1873. Her face is constructed from a few authoritative shorthand marks. The arm and hand that her head is resting against are so full of light they have the impact of a ringing bell. The sitter’s figure emerges from a series of blacks that economically telegraph her clothing and hair. It is difficult to discern in reproductions of the painting, but her dress is constructed from steeply crosshatched marks made by a flat brush that hardly follow the form, but from the distance of three or four feet congeal magically into her dress. Her reclining figure stands out brilliantly against a series of ochres and siennas representing the gold leaf surface of a Japanese screen.

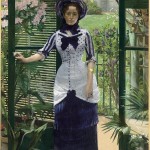

One of the surprises of the show was how good Berthe Morisot looked. She is a truly underrated painter. In their simplicity and directness her paintings seem to communicate the spirit of her sitters. In their direct naturalness they look like paintings far ahead of their time – for me they have a kinship with the paintings of Fairfield Porter. For their sheer weirdness, as well their use of fashion, the inclusion of paintings by James Tissot made sense in the context of this exhibition. Tissot is an artist with whom I have had a long love/hate relationship. A surprise for me was Albert Bartholomé’s In the Conservatory. It is a strong painting by an artist that I was unfamiliar with. Surprisingly the curators were able to include the actual dress that Bartholomé’s wife wore as she modeled for him. She died shortly after the painting was completed, which compelled Bartholomé to abandon painting in favor of sculpture.

Although I have sympathy with efforts on the part of museums to broaden the appeal of painting by tying it to some other discipline or element, I have mixed feelings about these strategies as well. It is as if viewers and museum professionals alike would be confounded at the prospect of dealing with a painting on its own terms. Last year I saw the wonderful exhibition Lucian Freud Portraits at the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth in Texas. If any painter has ever presented painting for its own sake and on its own terms in an uncompromising fashion, it is Freud. Many collections in the United States boast a painting by Freud. They are paintings of great strength and intensity and I am always happy to encounter them in the flesh. Seeing this show was a particular pleasure. The airiness and abundant natural light provided by the Tadao Ando building in Fort Worth provided the perfect circumstance to see the paintings. The exhibition was beautifully arranged with a comfortable amount of space between the paintings and presented a nice balance between the almost naïve, detail oriented early paintings and the caked on, painterly work which followed. I was also happy that the curators included a wall of etchings. The only mystery surrounding the show was why it was so under publicized and that the only two venues for the show were London’s National Portrait Gallery and the Modern Art Museum of Fort Worth.

Yet there is always a temptation on the part of museums to soften, mitigate and humanize such a cold eye – a small booklet that accompanied the show gave accounts of the several of the sitters and the circumstances surrounding the paintings. When I first encountered Lucian Freud’s paintings thirty years ago, information about the paintings and the sitters was pretty spare. While I was at the show I bought a copy of HYPERLINK “http://www.amazon.com/s?ie=UTF8&field-keywords=Jake%20Auerbach&ref=dp_dvd_bl_dir&search-alias=dvd” Jake Auerbach’s 2004 video, Lucian Freud Portraits. In the video Deborah Cavendish, the Dowager Duchess of Devonshire, tells a story about Freud and how she came to own Baby on a Green Sofa. The only information Freud gave her was that the painting was of a baby. Several years later he asked her whether she “still had that picture of Bella”. This is how she found out that it was actually a painting of the artist’s daughter. I must admit that I find these stories interesting, but I am also happy that I was introduced to the paintings first not knowing anything about them. I have studied them long and hard over the years simply as physical facts, running them over in my head, imagining Freud’s brush running over the forms and in a sense recreating them vicariously for myself.

The early paintings are fascinating. They hold all of the piercing intensity of a child’s or adolescent’s gaze and this intensity is capable of putting the viewer on edge. The scale of these paintings is frequently different than one imagines – always bigger or smaller than you would expect. After a time, working in this very linear, edge oriented manner began to give Freud headaches. Francis Bacon encouraged Freud to open up his approach and to work in a more painterly way. In a sense Freud is an artist who grew up in public and it is fascinating to watch the transition from his early to his late style. There is a period where Freud seems to be aping the style of Cézanne and to see what he can learn from it. Even as he hits his late style his approach to the paintings is different than one would expect. I have seen unfinished paintings of Freud’s where he seems to work in one direction from the center of the painting out to the unpainted edges rather than the overall modernist approach of balancing one part of the painting against another – exactly the opposite advice that I would give to a painting student. But it worked for Freud.

There were so many wonderful paintings in the exhibition that it is difficult to pick favorites. The Large Interior after Watteau is a painting that I spent some time with. The upper portion of his daughter Bella’s figure as she holds a mandolin – her arms and her head particularly – congeal in a beautiful way that is very different than it appears in reproduction. As a large and complex painting the viewer experiences it as I believe the artist did, in moments that grow out of one another and in a very tactile fashion. Guy and Speck was another painting that was a pleasure to see after seeing it in reproduction for so many years. The shifts in temperature on the suit give it a magical shimmer in contrast to the blue-black tie that is laid on in a flat, workmanlike manner. Part of the fascination of a Freud portrait comes with the blues and greys worked into the flesh that hint at subcutaneous veins or beard – again, these features summon an uncomfortable intensity. When he painted animals Freud did so with unusual sympathy – almost more than is evident toward his human subjects – and frequently one can sense the almost palpable relationship between the animal and human sitter, as is evident in Guy and Speck.

Freud’s style hits a kind of apotheosis in his late paintings. Again, it is difficult to pick favorites but Sleeping by the Lion Carpet, one of his paintings of Big Sue from 1996, is particularly strong. The contrasts between the cool light reflected from her thigh and breast, to the mottled Mars Orange at her upper arm to the shot through color of the lions against the sky in the woven carpet behind the figure contribute to making it such a full and satisfying painting. Not all of his late paintings find this resolution. Ria, Naked Portrait from 2007 is one such painting. A particularly awkward area is around the head, which takes on a clotted quality. One is unsure whether the painting was worked on too much or too little but the paint stays on the surface and the forms do not congeal or transform.

Regarding figurative painting in general, Linda Nochlin writing forty years ago, said it best. In a pair of articles that appeared in Art in America in 1973, The Realist Criminal and the Abstract Law she writes, “…Realism exhibits a remarkable flexibility and range, springing to new life, like a phoenix, just when it its adversaries proclaim it dead. Clearly the realism of today is not that same as the realism of the past. To condemn contemporary realism as resurgent academicism or trivial deviation from the mainstream – Modernism – is to falsify the evidence and prevent any just evaluation of its actual quality.” The only way to heighten the relevance of these words today, I suppose, would be to replace the word “Modernism” with “Post-Modernism”.

A critic could object to the continued fascination with painting from the observed world by casting doubt on the artist’s ability to achieve transparency in relation to the things painted – or for that matter its desirability, but this has been true throughout every age of history. No filter is ever un-mitigated. Everyone has an ax to grind – whether we know it or not. My vision is this: art for its own sake – not just representational painting – that exists for itself with an interior logic rather than as a vehicle for an agenda, should be admitted to contemporary art institutions with more frequency and with a far less grudging attitude. If viewers were able to encounter little islands of work like this in museums and contemporary art centers I think that it would reframe the art with its origins in an alternate set of strategies and make it look better too. One could think of it as the setting and the jewel – but of course there would be no agreement as to which was which.

Tim Kennedy

- Morisot, Woman at Her Toilette

- Manet – Lady with Fans

- Bartholome – In the Conservatory

- Sleeping by the Lion Carpet

- Large Interior After Watteau, Oil on canvas 73 x 78″