GEORGE WESLEY BELLOWS at the Columbus Museum of Art

By Kevin Ott

Columbus Ohio’s favorite son of the art world, George Wesley Bellows (1881-1925), has returned to his hometown museum, the Columbus Museum of Art, for a compact but enjoyable and educational show. Bellows was, and is, a titan of American early 20th century art. The Museum is renowned for the Howald Collection of American Art, and Bellows may be a cornerstone of that collection.

In his short life—just 44 years old when he died of appendicitis—he produced a body of work that is emblematic of the American art scene early in the last century. To really appreciate the depth of his work, the recent retrospective of his work at the National Gallery of Art and the Metropolitan Museum of Art was the place to start. Big and encompassing, the show I saw at the Met was a revelation, the variety unexpected—portraits, landscapes, seascapes, gritty urban scenes and, of course, the iconic boxing paintings. But, the smaller Columbus show is still successful at parsing his career, more a good short story or novella.

The work is arranged in somewhat chronological and thematic fashion through the 4 gallery rooms. The first gallery is Columbus-centric. It consists of family portraits, society portraits and some narrative drawings of his time at Ohio State University. The large portrait of his mother (1910), Anne Bellows, 44 years old when she gave birth to George, shows a big, strong 200 pound woman who appears stern, yet she is rendered affectionately. His father’s portrait (1906) reveals ambivalence toward the man who is described as a “philosophically rigid building contractor”. These and a couple of other society portraits are “in the grand-manner of Sargent or Chase”. And then there is a revealing drawing of fraternity hazing rituals which initially appears all fun-and-games, but a closer inspection seems to suggest some qualms on the artist’s part.

In 1904 Bellows moved to New York City and studied under Robert Henri at the New York School of Art where he became an integral part of the Ashcan School, a group of artists whose work focused on the underbelly of America at the time—the workers, the poor, their tenements and their lives. The second gallery focuses on this era and the work for which he is probably best known. The beautifully rendered blue-tinged, sun-touched snow of “Blue Snow, The Battery” is a wonderful landscape that in Bellows fashion depicts workers trudging off to work across a moodily blue-hued park. The difficult life of the common man is integral to many of these Ashcan era paintings. “Riverfront No. 1” (1915) is claustrophobic with tenement people crowding the shores of the Hudson for a swim. Socially, this is about the opposite of a Potthast beach scene. Especially beautiful is “New York” (1911), a large oil packed with buildings, horse buggies, trollies and people— commerce in action. It is colorful, yet the skies are gray and the building a bit hazy creating a somber feeling.

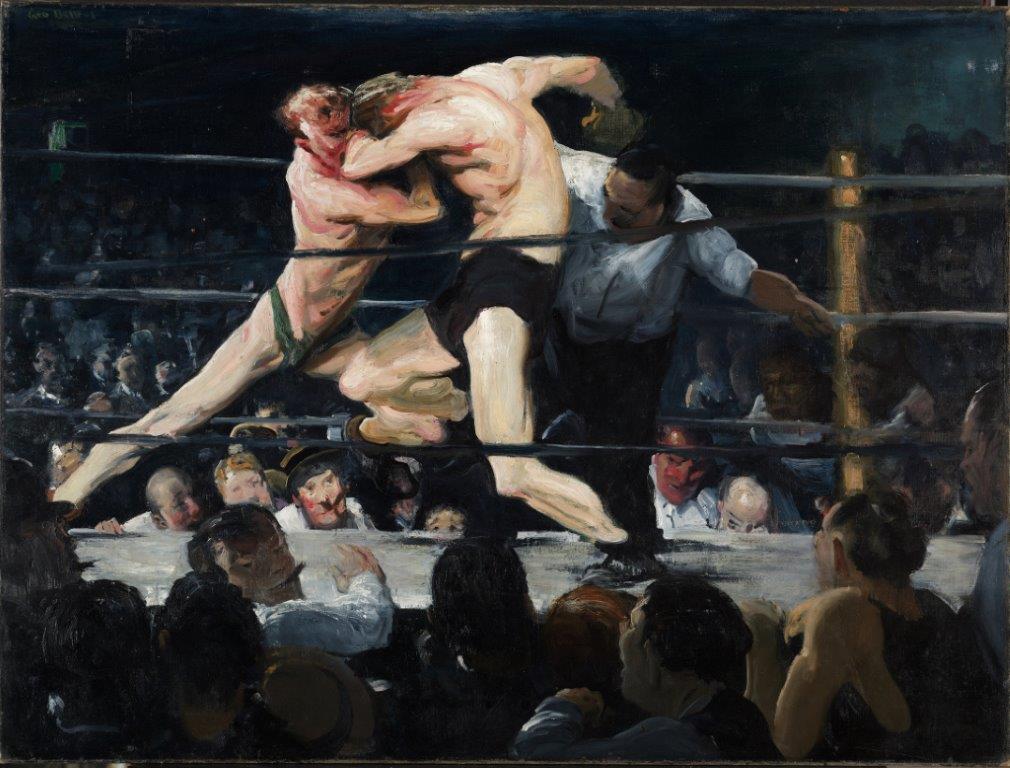

In this same gallery, “Stag at Sharkey’s” (1909) and “Club Night” (1907) let us visualize this century old sports world through these great pugilist paintings, all grit and action amid smoky ringside crowds. Just as action packed, but, I think, more interesting is “Polo at Lakewood”, the horses and riders a-swirl on a lush green field. It’s probably worth the trip for paintings in this gallery alone.

In the third gallery, a different side of Bellows is shown– landscapes and seascapes. Invited to Monhegan Island in Maine by Henri, Bellows was inspired to paint some very nice pictures of rocky, craggy coastlines and some typically gritty harbor scenes. The paintings, although not as impressive as the big Ashcan cityscapes, are still well worth seeing. Later landscapes, like “Romance of Autumn, Sherman’s Point” (1916) with its vivid colors, smushy strokes and skewed perspective are more successful.

The fourth and final gallery presents both the more socially conscious and the domesticated Bellows. A few larger paintings and several groupings of Bellows lithographs and related drawings fill the room. Later in life Bellows turned to family and his portrait of “Emma and Her Children” from 1923 shows both his fondness for his family and adeptness with this genre. But, Bellows was also socially conscious and had associated with a group of activists and artists called “the Lyrical Left” and had written and edited for The Masses, a socialist journal. The litho “The Germans Arrive” shows the atrocities of war in some detail. And his great lithograph “Billy Sunday” from 1923 depicts the accusatory fire of a maniacal preacher. Politics, unrest and outrage were often the subject of his prints. His lithographs, of which the Columbus Museum has many, are very well done, especially when he was collaborating with Bolton Brown, a magician of a printer. These prints can take on the appearance of charcoal drawings and are the most sought after of Bellows’ prints among collectors. Many of the prints are based on paintings, but they were an important to Bellows and not an afterthought. This gallery gives them their proper prominence, as did the retrospective at the National Gallery and the Met, where they were liberally sprinkled throughout.

It’s worth a trip to Columbus for the Bellows show, but be forewarned that the Museum is undergoing major change. A large addition is just getting under way and construction has closed off access to some areas of the museum. But, as you enter through a boot-legged side entrance, you can see the drawings of the new addition, which look impressive. And note that they have raised nearly all of the $100 million for this project.

Kevin Ott

- Bellows, “Stag at Sharkeys”

- Bellows, “Polo at Lakewood”

- “Riverfront No. 1”