by Matthew Metzger

Ron Thomas’ Take if from Me and Kim Krause’s The Eleusinian Mysteries ran concurrently at The Carnegie and Marta Hewett Gallery, offering a nice opportunity for a symposium (at least in writing) of two very different types of abstraction. I provide a bit more coverage for Thomas’ work simply because, to my knowledge, it hasn’t been written about before. Krause’s work has been written about before, and very well, leaving me less to add.

Take if from Me, Ron Thomas

Take if from Me is the first retrospective of Ron Thomas’ work, and a very impressive one. It’s also Matt Distel’s first major exhibition at The Carnegie since becoming Exhibition Director. If this show is a harbinger for the quality of shows to follow, we have something to be excited about.

Thomas died in 2009, relatively unknown. This unfortunate obscurity tempts us to approach his art from an “outsider art” perspective, and Distel makes those connections to the work. I fault no one for using the pejorative term because even MOMA – our grand arbiter of art – uses it. But the distinction between “outsider art”, “self taught” or “visionary”, and academically or officially sanctioned art only obfuscates the fluid and rich history of women and men making artful objects. Our endless taxonomies tend to do that, although they are supposedly useful to academics, to what end I can’t tell (as an aside, compare the banal term “outsider art” with the much more eloquent and lively French equivalent, art brut, further confirmation to me that the French may be worse than us at everything except living life, an inconsequential matter for some). Nevertheless, even accepting the “outsider art” dichotomy, I’d still argue that based on Thomas’ work the term isn’t fitting.

Formally, Thomas’ paintings fall within the difficult history of geometric abstraction. Geometric abstraction got its start a few decades before Thomas’ 1943 birth with Malevich’s constructivism and suprematism, idealistically seeking the “supremacy of pure artistic feeling”, a rather grand endeavor. It quickly lost its high art luster when embodied in design by the German Bauhaus school, which sought to use the purity of geometric forms in everyday design to propel the modernist canon (progress, idealism, utopias, those sorts sentiments unpopular today). The interplay between high-art geometric abstraction and design begins but doesn’t end there. Later, American artists like Donald Judd, Ellsworth Kelly and Frank Stella re-explored constructivist forms to get at the essence of a subject through absolute reduction of form and materials. Design and corporate culture again followed, with everything from minimalist advertising (alla VW’s “Think Small” campaign) to the use of geometry and repetition to convince consumers to buy things they didn’t even know existed. Geometric abstraction has repeatedly oscillated between high art, on one hand, and design, advertising and even propaganda on the other. It became the go-to motif for more than one South American dictator.

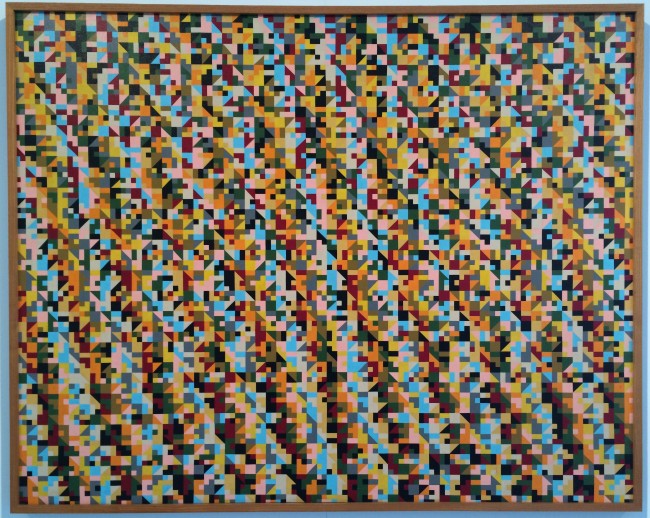

Thomas was trained at the University of Cincinnati DAAP with a degree in Advertising Design. He worked for some of the same large corporate ad agencies that extolled geometric forms and repetition as models to, simply put, get people to want things they never really needed. He would have been aware of geometric abstraction’s oscillation between high art and institutionalized advertising design. In fact, I think he’s making subtle reference to the interplay in his work. Much of it has a tight repetition that echoes the repetitive pulse of advertising in our graceless media. Certain paintings, particularly the ones composed with the help of randomness, take the form of a scrambled television screen, a light-night post-advertising (post-apocalyptic?) world. If this reference is intentional, it’s a very astute nod to art history and design. Not the stuff that “outsider art” is typically made of, unless outsider art is simply any art made by anyone who lacks an MFA.

Thomas’ work is wide ranging and, in postmodernist tradition, draws on numerous and diverse references. Aside from geometric abstraction it invokes op art, pueblo indian patterns, Navajo rugs, the French surfaces/supports movement, Hindu and Buddhist Mandalas, Pink Floyd album covers, minimalist music, Tantric imagery and Islamic art. He made photo collages with family pictures that have Mandala-esque centers and quadrants. He used shaped canvases ranging from triangles to nonagons. His palette varied from pastels to bold cadmiums. Despite this diversity, the work isn’t of an abrasive, postmodern diasporic quality. Some paintings are symmetrical with a very certain center, while the composition of others is determined by chance. All have in common a balanced geometry, meticulous precision, repetition and tightness that at first impression belies the mystical aspects that, according to the exhibition catalogue, Thomas openly expected of his work.

The Mandala and Tantric imagery we see in Thomas’ Change and Alpha Redux, among others, is Thomas’ most obvious foray into the mystic. But as soon as we start recognizing the mandala form as a Mandala in the historical sense (which is to say recognize it semiotically, as a sign or with language), we in part destroy its effect as a vehicle for achieving a higher state of consciousness. It becomes intellectualized, if you will. A subtler (and, for me, more effective) invocation of mysticism is Thomas’ use of randomness to compose paintings. In Flags of all Nations he rolled die to randomly choose from a group of predetermined shapes and colors. Chance has been used before in the history of abstraction (what hasn’t?). But for reasons different than Thomas’. Ellsworth Kelly used chance in his 1951 Colors for a Large Wall, where he randomly determined colors with the idea that he could place himself and painting as a whole outside of what he saw as the limits of subjectivity. Gerhard Richter has been using chance off and on for the last 40 years, the most notable his 4900 Colors from 2007. Richter’s objectives are always murky, being the painter of doubt and irony, the master of plurality of expression, and not exactly forthcoming, but it seems his 4900 Colors is simply about the pure joy of finding form in randomly applied bright colors. Thomas, on the other hand, used chance with the paradoxical purpose of appealing to chaos to create harmony. As a way to “open chaos, so that magic arises”, to quote Carl Jung. Jung was drawing from Jewish mysticism and the Lurianic Kabbalah notion that “original chaos” (i.e. the chaos that ensued before the world was created) is the source for true creativity.

Chaos theory in modern art arguably begins with John Cage who, along with his successors Steve Reich and Phillip Glass, was criticized in part for minimalist music’s correlation with the repetitive pulse of advertising used to create inauthentic desires (compare Thomas’ use of repetition discussed above). Unfortunately we probably will never know whether Thomas was closing his circle (or Mandala) by reference to (i) geometric abstraction’s relation to advertising design, (ii) to chaos, chance and minimalist music, and (iii) back to the repetition of advertising. We won’t know because he’s now dead and his art didn’t get the attention it deserved when he was alive. I’ll let the reader delve more deeply into these rather interesting issues at his or her leisure, hopefully after seeing Thomas’ retrospective, which I highly recommend.

The Eleusinian Mysteries, Kim Krause

Kim Krause’s The Eleusinian Mysteries is an entirely different type of abstraction, more lyrical than geometric. The paintings are hung extraordinarily in the space at Marta Hewett Gallery, where you can stand in the middle of the back room, forget yourself, and be nearly swallowed by them. Weaves of ribbons occupy aqueous, Mediterranean color fields. At their best, the elliptical forms move beyond the borders of the canvas to viscerally engulf us, the viewers, as participants in the push and pull of the cycles of descent, search and ascent. These cycles are part of the ancient Greek Eleusinian Mysteries myth, the show’s namesake, wherein Persephone is abducted from her mother, Demeter, and taken to the underworld (the descent); Demeter looks all over Hades for her (the search); and, finally, Persephone and Demeter are reunited (the ascent). The mediterranean colors are in keeping with this mediterranean myth. After all, the Parthenon was originally brightly painted, so it goes.

Krause’s paintings seem to set up multiple dialectics: of flat, tight color with loose, atmospheric light; of push with pull; of precise lines with dripping, nebulous paint. In the exhibition catalogue the paintings are accompanied by seemingly unrelated poems by Matt Hart, another dialectic between painter and poet far from arriving at any Socratic truth (the ultimate aim of dialectics, traditionally). Of course, the dialectic is itself a Greek concept, and embodies the “search” that, in the end, these paintings are all about. Is it insignificant that the search in this instance is metaphorically being conducted in Hades? A dialectic also embodies a resolution, though I don’t know that these paintings, or the paintings paired with the poems, resolve anything. But for me this isn’t a bad thing. In fact, non-resolution can be a resolution in itself, a maddeningly paradoxical thought. In short, these paintings are comfortable with ambiguity; with a path toward realizing the frustrating ungraspability of paradox; a descent, search and ultimate ascent.

Stepping back, Take if from me and The Eleusinian Mysteries also set up a dialectic of sorts, a very tiny foray into the vastness of abstract painting. The shows are rich with meaning and with aesthetic pleasure, that precarious balancing act that most abstract painting grapples with. Both Krause and Thomas find a graceful balance. Also graceful is the presentation of the paintings at The Carnegie and Marta Hewett Gallery, both venues that are not historically known for such shows. Here’s to hoping for more to come.

Matthew Metzger is an artist, designer and furniture maker based in Cincinnati. His paintings are represented locally by Miller Gallery, and his furniture by Voltage, as well as other galleries and design showrooms nationally. His website is at metzgerfinearts.com.