by Karen Chambers

Alice F. and Harris K. Weston Art Gallery through March 22

Nellie Taft was a hometown girl, born in 1937 in Indian Hill and died in 2012 in Boston. She attended Lotspeich and Hillsdale Schools in Cincinnati, which answers the burning question among natives: Where did you go to high school? She finished her high school education at St. Timothy’s School in Baltimore.

Nellie (I’ll explain using such a familiar way to refer to her in a bit) was the great-great grand niece of William Howard Taft and had connections to William Henry Harrison. She was also a member of the Taft Broadcasting Company family. Ca-ching. Lineage counts in the Queen City.1

Befitting her social standing and her financial resources, not to mention her artistic leanings2, of course, she served on the national committee at the Whitney Museum of American Art from 1993 until her death in 2012. Chairwoman Flora Whitney Biddle, granddaughter of the Museum’s founder described her in a Boston obituary as “both a lover and creator of art. Spirited, talented, and fun to be with – we all treasured her involvement.”

Carrie Blackmore Smith in “Lives Remembered” in The Enquirer, wrote, “Described as witty, courageous, and vivacious, she could fly a plane, drive a speed boat, and traveled the world, from India and China to Portugal and Spain, Colombia – even lived a year in a log cabin in the Scandinavian region of Lapland, in the Arctic circle.” (Damn, I would have liked to have known her.)

In The Boston Globe obit (Taft moved to Boston in 1990 to study at the School of the Museum of Fine Art Boston), Anita Lincoln, a friend and neighbor from Back Bay, said, “Because of her artistic sense, she was always beautifully presented, She dressed impeccably. She just had exquisite taste.”

Withstanding all of that, Nellie was anything but a society grande dame with Sunday painter syndrome. A little deeper look into her C. V. reveals her artist bona fides. After two years at Briarcliff, she transferred to the progressive Reed College in Oregon where she first began to paint in 1959.

In 1966 she received a B. A. in art history from Columbia. (Barak Obama was right when he noted you can’t make a living as an art historian. He apologized, averring that art history was one of his favorite subjects in high school. But he was spot on: Art history doesn’t lead to a lucrative career path, as I well know. Also, I’ve noticed in my recent reading of chick lit [don’t ask], art history is the go-to profession for middle-aged divorcées. But I digress.) A little more practical was her 1968 M. A. degree in art education, also from Columbia, which she did use.

Back in Cincinnati, Nellie spent 1982 at the Art Academy before moving to Boston where she earned a diploma from the School of the Museum of Fine Art in 1990 and graduated from the fifth-year program the following year. In conjunction with that, she received two traveling scholarships and spent a year in Rome.

Nellie was certainly aware of art history and contemporary artists, and it shows in the retrospective at the Alice F. and Harris K. Weston Art Gallery, curated by Denny Young, former curator of painting at the Cincinnati Art Museum and, by-the-by, a cousin. The exhibition, “Nellie Taft: Odyssey, A Lifelong Journey through Art,” is described as a tribute to her. (Tribute, huh. Sounds like a “tribute bands,” which play the hits of well-known bands.)

Nellie’s odyssey was not on the Weston’s original 2013-2014 schedule as released. But Harrington explains there is always “a challenging place in our schedule each year when we present “CANstruction” in the upper gallery that leaves a three-week gap where we have had to either extend or stagger exhibitions in the lower galleries. Utilizing this time and shortening our installations allowed us to present Nellie’s exhibition without disrupting the remainder of the season.”

The Taft family had brought the work back to Cincinnati last summer and wanted to present it as soon as possible since Nellie had died in December 2012.

The title is particularly apt. The exhibition does trace her lifelong journey, an intellectual and artistic quest. As I made a circuit of the gallery, which Harrington hung with a view to formal connections not chronology3, I could pick out those who influenced and inspired her.

While at Columbia in the late 1960s, Nellie had a studio in a loft in lower Manhattan and presumably got to know the Abstract Expressionist crowd. (Did she hang out at the Cedar Bar?) Alison Hunt in a 1991 profile in The Beacon Hill/Bay Bay Chronicle writes she was “involved with emerging artists such as Willem de Kooning and Franz Klien (sic).”

Whether or not there was a direct involvement, it’s easy to pick out the AE influences, inspirations, “tributes” in paintings from the 1990s – a little after the fact.

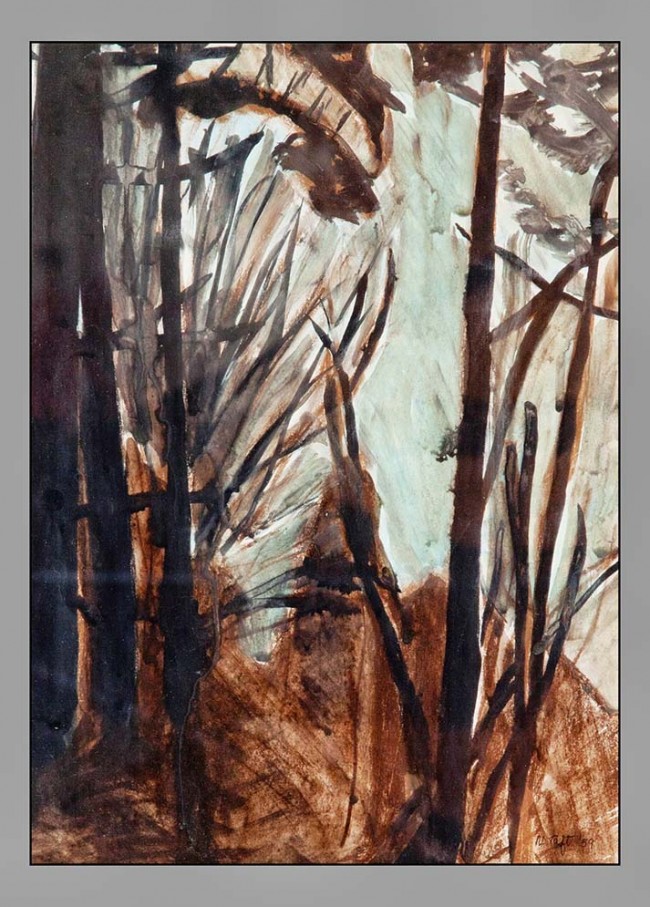

Although I will say that the earliest works in the show done in 1959 when she was at Reed College, the Jungle series (to my eye her “jungle” looks more like a stand of aspens or alders or birches – tall slender trunks reaching upward, not a dense tropical forest), does show a touch of Kline as well as Chinese brush paintings.

In Heart Soundings, 1996, there are touches of de Kooning, Cy Twombly, as well as graffiti art, also after the fact. This painting is part of the Palimpsest4 Series and beneath an active surface you can discern her handwriting.

The strong, jagged shapes and paint application in After and Before, 1991, recall Clyfford Still while her narrow vertical canvases evoke Barnett Newman as does the single sculpture in the exhibition, the monolithic Vanderwalker.

PHOTO:

PHOTO:

Sea Sand seems to reference Joan Mitchell or a more robust Helen Frankenthaler. You can easily see the connection in the Dry Salvage series to Robert Motherwell’s black paintings or a very restrained Rauschenberg combine with the attached corroded iron pipe, which she called “sea scrap.” Untitled 2 quotes Rothko: a white rectangle floating on top of a black field occupies about three-quarters of the canvas; the far left quarter shows a door into a room with a drum or table (rather like two segments of Brancusi’s Endless Column) lying on its side.

PHOTO:

Nellie’s debt to Jasper Johns is obvious in the 2002 giclée print Oculus III , where she’s encircled an American flag with a paler band.

Both the subject matter and handling of watercolor of Hydra, Greece, 1988, bring to mind Milton Avery. The kinship is apparent with how delicately she’s blocked in areas like the orchid sea and the fast moving clouds of the sky.

PHOTO:

The 1989 paper cutouts of nudes surrounded by abstract shapes blatantly reference Matisse, and her Tuscan Hill Town, San Gemignano, could easily be from the south of France with its cubic houses and is almost pure Cézanne although her palette is less sunny.

Thanks to Nellie’s meticulous scrapbooking, I could read contemporaneous reviews of her work and other comparisons popped up with West Coast artists like David Parks, Richard Diebenkorn, and Fairfield Porter apparent in the style and palette in her landscapes and figures. Gerald R. Kelly in a 1990 review in The Martha’s Vineyard Times described Allegro as looking “a bit like Klee doing Mondrian.”

But despite all this “name the influence” game, I do not find Nellie’s work derivative. I’m not sure why I don’t, but I don’t.

And equally puzzling to me is how I can see this body of work as coherent as she moves from a kind of realism to pure abstraction, but not in any linear fashion. And she uses such a wide variety of mediums: ethereal watercolor; thick oils; charcoal; monotypes and giclée prints; incorporating found materials as diverse as bark, slate, and corroded iron pipe. But it’s her absolute love of material and techniques that brings it all together.

PHOTO:

Harrington says that one of things that attracted him to Nellie was this range of subjects and mediums. He points out that abstract elements appear throughout her work, even in the earliest somewhat representational works, the Jungle series. Harrington explains the aim of the show was to “represent all avenues of the work.” It does.

Photo:

But back to Nellie, and why I feel that I can call her that. Somehow – and trust me I have no clue as to why or how – I can imagine Nellie in her studio, standing at her easel (the works are all easel-sized with the largest, Untitled 2, measuring only 54” x 64”). I can see her considering what mark to make or figuring out how to attach that heavy hunk of iron on a canvas and then mount the whole thing on slate, ending up with a piece that weighs about 50 pounds and really isn’t that large.

Somehow I feel privy to her artistic process, informed by her art history background and intimate knowledge of the contemporary art scene, her upbringing, and her curiosity and obvious delight in material.

I’ve often heard artists being advised to create a coherent body of work rather than go off in all directions, that homogeneity is easier to digest than a smorgasbord of styles. Even though this retrospective is a real smorgasbord, the work does hold together. And it holds together because I feel a connection to it. I have a sense of Nellie’s personality. That’s what marks each work. It’s personal, which has led me to share (probably too much) of myself here. And if the review is disjointed, that’s Nellie, too.

Kudos to Young and the Weston for giving us the opportunity to see – not just glimpse – Nellie Taft the artist.

PHOTOS

FOOTNOTES

1 Nellie was married to Arthur Middleton Gammell. Their union ended in divorce, apparently amicably since Nellie remained friendly with his nieces until her death. Although I don’t know the dates of their marriage, I can hazard a guess that it was between 1966 or 1968 when she was studying in New York at Columbia University and 1982 when she returned to Cincinnati to attend the Art Academy.

2There seems to be an “art gene” among the Tafts. Nellie’s grandmother was a gifted watercolorist, and her nephew Perin Mahler is an associate professor of art at Laguna College of Art and Design, in California and directs the Master of Fine Arts program.

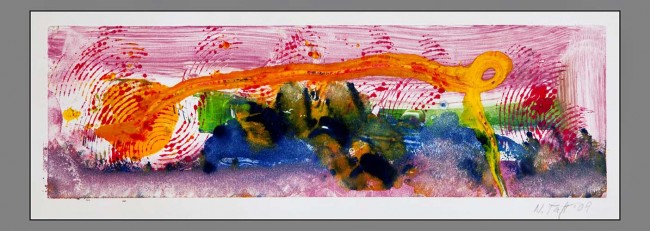

3 The most recent group of work included are monoprints from 2009, but she had tried this medium earlier. The formal connections that Harrington wanted to show are perfectly illustrated by two of them: Viet Nam (sic) Rice Paddy from 1987 and the more abstract 2009 Gold Stripe, which share the same dimensions: 15” x 22”. In the former, Taft gives us a panoramic view with a high horizon line of a verdant field, or what we read as a field given the title. There’s a zip of neon pink in the distance underlines the blue sky.

PHOTO:

That same pink is seen as a band of squeegeed color at the top of the later Gold Stripe. Starting from a ball, a gold line streaks across the width of the print, loops, and then dives to the ground. If Nellie hadn’t given the earlier work a title that pointed us to representation, it would have seemed as abstract as Gold Stripe.

4“Palimpsest” is defined as “1: writing material (as a parchment or tablet used one or more times after earlier writing has been erased 2: something having usu. diverse layers or aspects apparent beneath the surface . . .”

Nellie Taft: Odyssey, A Lifelong Journey through Art, Alice F. and Harris K. Weston Art Gallery, 650 Walnut St., Cincinnati, OH 45202, 513-977-4165, www.westonartgallery.com. Through March 22. Tues.-Sat., 10 a. m.-5:30 p. m., Sun., noon-5 p. m.

April 5th, 2014at 10:24 am(#)

Good information, thoughtful comments, and a beautiful presentation. Thank you.