by Karen Chambers

“CCAC (Clifton Cultural Arts Center) will have a beautiful show with these five artists.” That’s how the curator, Yvonne van Eitjden, described the exhibition of two photographers, two wood sculptors, and one painter (herself [Why, oh why, do curators include their own work in exhibitions? How about they make a pact with their curator/artist friends? Curator/artist “A” could include curator/artist “B” in his/her exhibition and forgo showing his/her own work in it, and curator/artist “B” would do the same. It would be, at least marginally or obviously, less self-serving. Whatever.])

Although the show is billed as “A Group Exhibition Curated by Yvonne van Eijden,” the announcement suggests something else: five solos since each of the artists has a separate show title:

Wood sculptor Robert Fry: “Together – Something – Different”

Photographer Wes Battoclette: “Appalachian Club – All that Remains”

Photographer Ann Segal: “Gifts from the Sea – Larger than Life”

Wood sculptor Stephanie Cooper: “Wood Spirits”

Painter Yvonne van Eijden – “Are we Seeing and Listening Clouded by our Memory of the Past”

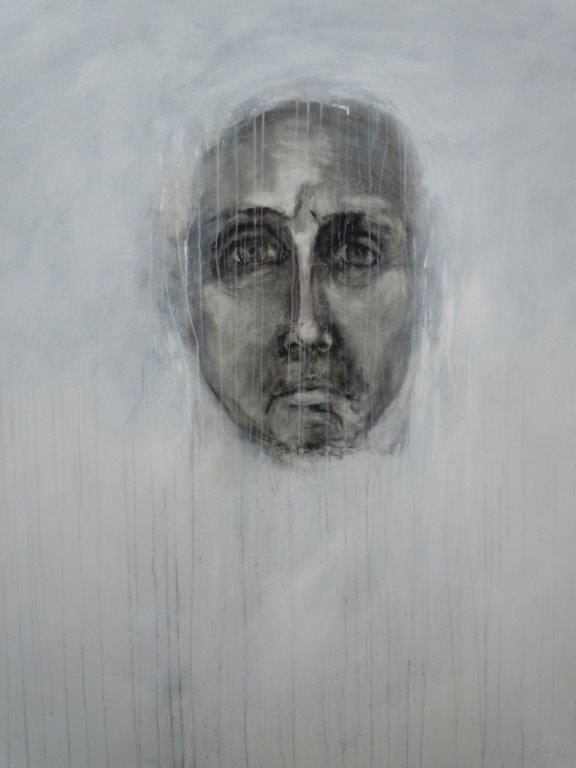

PHOTO: Yvonne von Eijden, Are we Seeing and Listening Clouded by our Memory of the Past Nr. 1, acrylic, charcoal, pencil on canvas (4344), 2014

Well, this show is what it is: an interesting group of artists.

In the expansive lobby of the 1906 Beaux-Arts school that has been turned into the CCAC, Robert Fry’s sculptures made from recycled wood dominate.

The Covington sculptor works with salvaged wood: fallen trees, floor joists, sticks, recycled wood from buildings and yards. He explains, “Most of my work develops out of the challenge of making concrete ideas and concepts from the material that surrounds me, which is primarily abandoned and repurposed wood.” He continues, “Mostly I let the nature and history of the material suggest the direction of the piece. I like to contrast colors and textures, making decisions organically, adding and subtracting elements as I go.”

I was drawn into the imposing space by Fry’s 2009 Together Something Different at the back of the installation. The construction looks like a cabana, but the form also reminded me of the bonnet of a baby buggy or a nun’s coif. Whatever it evokes, there is always the element of protection – shelter. I could imagine myself sitting in the shelter in a lotus pose or, perhaps, a child sitting Indian style.

The title Together Something Different aptly describes how he assembles individual, nearly identical pieces of wood, to create something “different.” Here the 65” x 65” x 65” structure is composed of long lath-like strips, ¼” thick and six inches wide. The wood came from a white oak tree in a friend’s yard “after they had cut it down for safety reasons. I cut it up with my chainsaw into more manageable pieces and had them resawn (sic) for a number of different sizes for several sculptures.”

For Together Something Different, Fry dried the strips of green wood over a form, bending them to his own purpose; the process took a year. He joined about 10 of the bentwood strips at the base, securing them with phillip’s head screws. He then fanned out the individual strips, nailing each one to the next with copper tacks.

The use of wood, how Fry constructs his sculptures using basic carpentry skills, and the forms reminded me of Martin Puryear. The two artists share an affinity for the material, an appreciation of the craft, and a post-minimalist aesthetic. It didn’t take much to find two Puryear sculptures similar to Fry’s.

There is a kinship between Fry’s Together Something Different and Puryear’s 1980 Bower, in the collection of the Smithsonian American Art Museum. Puryear’s Sitka spruce-and-pine sculpture, which measures 64” x 94 3/4” x 26 5/8”, is built on a base of two half-round pieces bent and joined to make a lozenge or canoe-shape. Strips, like Fry’s, rise from it and curve upward, meeting to create a dome that’s been squashed together on the sides, more ogival than round. Puryear’s sculpture is closed and cannot be entered unlike Fry’s, but it still suggests shelter.

It’s impossible not to think of Puryear’s rustic Ladder for Booker T. Washington when you see Fry’s bit more refined oak-and-walnut One Step at a Time, 2011. Because of Washington’s belief in incremental change, Fry’s title would fit Puryear’s sculpture, too, especially since it was titled after the African-American artist made it in 1996.

Regardless of when Puryear arrived at the sculpture’s title, it does reference a historical figure. Born in 1856, Washington was the last generation of African-Americans born in slavery. From 1890 until his death in 1915, he was the predominant leader in the community, but he was controversial. Instead of confronting segregation and Jim Crow laws, Washington believed that the best way to win equal rights was to show “industry, thrift, intelligence, and property.” He advocated building the community’s economic strength and pride by focusing on self-help and education. This strategy, which became known as the Atlanta Compromise, was articulated in a speech Washington delivered in the southern city in 1895. Those ideas ran counter to the more militant approach to securing equality espoused by W. E. B. DuBois and the NAACP, which was founded in 1909 and would shape the later Civil Rights movement.

Both sculptures represent a journey or ascent. However, there are marked differences. First Puryear’s is much taller — 432” to Fry’s 144”. The former narrows from 22 ¼” to only 1 ¼” at the top, creating a forced perspective to make it seem even longer, extending into “infinity,” it represents the ongoing struggle for equal rights. Fry maintains a uniform 34” width.

Puryear’s side rails are polished golden ash saplings from his property in upstate New York and are crooked, suggesting the uneven course of the Civil Rights fight. Fry’s side rails are unfinished red oak salvaged from an Indiana farm; they are 1/ ½” x 6” and unfinished: something remains undone. Fry’s rungs are “dowels,” each hand-carved so they vary somewhat. He’s grouped them in vertical rows of three, but has intuitively left out a few. Progress is not orderly.

Fry revivifies the discarded while Wes Battoclette records ruined spaces in his 40” x 26” archival inkjet prints from the series “Appalachian Club – All that Remains.” Three of the five color photographs on view are of the abandoned rooms of the Wonderland Hotel – what a great name for this derelict hostelry, which is quite the opposite of Alice’s wonderland.

Battoclette came across the Wonderland Hotel in Elkmont, Tennessee, when he was hiking and camping in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park in 2006 and photographed it two years later. Elkmont was a summer retreat for wealthy Knoxvillians, and the Wonderland Hotel, which has since burned, was the main hotel.

In Wonderland Hotel Annex Room #1, the paint has peeled off the walls leaving huge patches of bare plaster, and the floor is littered with confetti-like chips of the institutional turquoise-green paint. There is a phantom image of the rectangle mirror that once hung above a bathroom basin in the room. On the back of a door that connects to an adjoining room is what looks like a spike but is more likely a clothes hook that has been bent down.

Adding to the unease of these abandoned rooms is Battoclette’s high-keyed palette. The louvered transom of the door to the hall seen from the room adjoining Room #1 glows neon green, and the walls of the hallway of Wonderland Hotel Annex are a bilious green.

In the second photo, a strip of moss-like carpet extends into the distance in an exaggerated perspective. This impression is aided by the horizontal beadboarding that speeds the eye along the hallway. It is lined with doors that seem to repeat endlessly as if reflected in mirrors, like Lucas Samaras’s Mirrored Room, 1966, or Yayoi Kusama’s Infinity Mirror Room, 2012. But the room at the end of the hallway, seen through an opened door, stops the eye.

Fry resurrects the discarded, Battoclette documents decline, and Ann Segal celebrates life in her photos of seaweed that capture every detail of the green aquatic plants washed up on the shore. Segal has been “fascinated by the elemental, primordial qualities of sea life, specifically seaweed,” for decades.

Segal lived in California from the mid-1970s but returned to her hometown of Cincinnati in the early 1990s. Shortly after being invited to show here, she made a trip to northern California where “these gifts from the sea presented themselves to me, and I began a personal, in-depth inquiry, engaging and intensifying all my senses as I explored/photographed.” For her, the “images are profoundly personal and universal at the same time. Microcosm=macrocosm/personal = universal. Life is a beach!”

For these photos printed on Styrene, Segal has positioned herself above the seaweed making it appear monumental and causing a moment of dislocation because of the vantage point and scale. If Segal had moved in closer, the recognizable plant would have become an abstraction.

This happens in Mussel Shell; only its title gives it away. The shell, described in areas of black and gray, could be a boulder or rock overhang. The shell’s iridescent green, blue, and lavender interior could be water, just a slick or maybe a pool. The photo’s ambiguity made it less interesting to me although one could expect the opposite as it challenges the viewer to decipher the image.

While capturing the essence of life in her seaweed pictures, Segal forever arrests growth, but it doesn’t feel like a Henri Cartier-Bresson “decisive moment,” perhaps because growth is such a slow process. Even in time-lapse photography, you’d be hard pressed to declare any moment decisive.

Stephanie Cooper has, however, captured decisive moments with her primitive carved-wood sculptures of figures caught mid-action. Cooper describes the tableaux as “small dramas . . . determined by a simple gesture.” Even though the charming, folk-art-like figures are static, she gives several the potential for actual movement with simple mechanisms of gears, pulleys, and rods, designed to make the figures move like puppets.

Cooper has long been intrigued with simple machines of bygone eras. Her interest “goes back to visits to the Smithsonian History and Technology Museum (Cooper was born in northern Virginia) and my fascination with Rube Goldberg’s cartoon inventions. The moving parts that carry the images into time, creates an experience with sculpture that is candid and mysterious simultaneously.”

Cooper’s figures could be interpreted as “everyman” or “everywoman” since they are anything but individualized. Their faces are impassive, blank-eyed with mouths neither frowning nor smiling. But then Cooper uses the definite article “the” in her titles.

For example, it is The Man Juggling, not a man juggling. This man is dressed rather formally in a suit, tie, and hat. He stands with outstretched arms with four orange balls, threaded into an arcing wire, levitating in front of him. A woman stands at right angles to him, wearing a simple, nearly ankle length, scoop-necked, and sleeveless black dress. It’s anything but a chic LBD – little black dress. Completing the scene is a bitch standing alertly on her back legs, head upraised, ready to catch an errant ball.

The Man Juggling is mechanized with simple machinery driven by a crank handle. Squeaking when turned, it makes the man’s arms move up and down in the act of juggling; the dog “jumps” excitedly forward and back; the woman’s head moves side to side, turning toward the man but never actually looking at him. (A short video of the piece moving can be seen on the Facebook page of Cooper’s daughter, Selena Reder.)

Yvonne von Eijden, Are we Seeing and Listening Clouded by our Memory of the Past Nr. 2, acrylic, charcoal, pencil on canvas, 72” x 70” (4346), 2014

The humanity of Cooper’s figures prepares you for Yvonne Van Eitjden’s paintings, or vice-versa since the latter’s work shares the lobby space with Fry’s sculptures and is encountered first.

The Dutch-born visual artist and poet presents three large canvases from her charcoal, pencil, and acrylic “Are we Seeing and Listening Clouded by our Memory of the Past” series. The answer is obvious: of course we are.

(It’s noteworthy that van Eijden has not paired two senses – seeing and hearing – but has chosen “listening,” which implies a mental process and engagement.)

A third person statement explains, “Yvonne has always been intrigued by how communication takes place, how to read and listen between the lines.” It goes on to say that because she now speaks and thinks in English and only rarely in her native Dutch in her professional life, she has “become very aware of the tenuous interpretation one can sometime (sic) obtain from the spoken or written word.”

(I kept tripping over “tenuous,” unable to decide if she took poetic license, had deliberately chosen to be obscure, or just made a poor word choice.)

Yvonne von Eijden, Are we Seeing and Listening Clouded by our Memory of the Past Nr. 3, acrylic, charcoal, pencil on canvas, 72” x 70” (4345), 2014

In the “Are we Seeing and Listening Clouded by our Memory of the Past” paintings, black, white, and gray ovoid faces emerge from a fog of white, dirtied with streaks of gray drawn under the acrylic veil, a rather flatfooted symbol for clouded memory. The disembodied heads with their sad almond-shaped and heavily hooded eyes stare outward without seeing. They look, they listen, but with closed lips, say nothing. All communication goes on in their heads. It’s an interior dialogue. Fine.

Immediately after viewing the show, I serendipitously heard a July 2011 TED talk on NPR. Julian Treasure was discussing “5 ways to listen better.” (He’s chairman of The Sound Agency in the U. K., which “is dedicated to proving that good sound is good business.” The company creates soundscapes primarily for retail environments.)

Treasure contends, “We are losing our listening.” He goes on to say that we spend “roughly 60 percent of our communication time listening, but we’re not very good at it. We retain just 25 percent of what we hear.” It’s a serious problem “because listening is our access to understanding.”

Van Eijden gets that and communicates it with her dreamy images.

Although I liked the work on view, I also wished van Eijden had done more than just present art that she happened to like. Still she has succeeded in mounting “a beautiful show.”

A Group Exhibition Curated by Yvonne Van Eijden, Clifton Cultural Arts Center, Clifton Cultural Arts Center, 3711 Clifton Ave., Cincinnati, OH 45220, www.cliftonculturalarts.org, Mon. 10 a. m.-5 p. m., Thurs. noon-7 p. m., Sat., 9 a. m.-1 p.m. Open when classes in session. Through April 12, 2014.