Street photography was a movement initially made possible by cameras that were small, film that was fast, and hands that were steady. It refreshed photography as an art form by opening up an almost unlimited source of unscripted narrative. It required some skills of the photographer not unlike those needed by an undercover cop: you had to be able to fit in anywhere without losing sight that you were always outside of what you were observing, and you had to be ready to be in someone else’s face without turning every attempt to photograph into a standoff. It required improvisatory verve and entailed risk—perhaps of all sorts, as not everyone cares to be caught in the act of being themselves. Like work from the best photojournalists reporting back from the warfronts of the world, street photography allows the audience to go places and see people they would be unable or merely disinclined to see on their own. There is something democratic about street photography, though it is a genre not obligated to hold people in particularly high estimation. It is a test of your sense of citizenship, both for those being photographed and those doing the photographing. Classic street photography is a forum for examining what one does, and what one is, in public.

What you think street photography is may depend on who you think the archetypal street photographers are. Winogrand, let’s stipulate; Helen Levitt and early Meyerowitz; Willy Ronis and Robert Frank and Vivian Maier and Bruce Davidson. It’s interesting how allowing other figures into the group requires you to ask some fundamental questions about the nature of the genre. We can allow Atget in if we think that the streets do not have to contain any people. We can allow Dorothea Lange in if we think that street photography does not require streets. We can allow Diane Arbus in if we accept street photography’s confrontational nature and do not expect the photographer to aspire to some sort of fictive invisibility.

Very little of this is what Brian Sholis, the Cincinnati Art Museum’s new Associate Curator of Photography, is trying to capture in his first big show for the Museum, “Eyes on the Street.” In it, he proposes that there is greater potential in photography’s urban engagement than more or less candid shots of individuals distinguishing themselves from their crowds. And in the show’s works where there is a focus on the faces and bodies of individual people, it is hard not to be aware of how our responses to taking pictures of people without their permission has changed in an age of surveillance. (The concealed metaphor of “taking” a picture—rather than, say “making” one—has not been as poignant since the days when members of various tribes did not want to sit for photographers for fear of what they would be surrendering of themselves.) As Sholis notes in his brief but excellent essay produced to accompany the show, street photography today is likely to raise a broad range of “social, political, legal, and architectural” questions. Sholis’s show affirms that we like to watch, but it places our watching in a variety of contexts, and sees the photography of urban culture, in Sholis’s terms, as “part of a greater system of watching.” I must say that I missed a more explicit acknowledgement that street photography could play an important role in urban political advocacy—before there was Garry Winogrand, there was Jacob Riis—and though it may be the romantic socialist part of me speaking, I was sorry not to see who has inherited from Lewis Hine the conviction that we are never more uniquely ourselves than when we are working together. Though the show as a whole does relatively little to celebrate the physiognomy and interpersonal entanglements of the individual in the conventional ways that street photography has done, Sholis has brought together a range of ways to show quite forcefully that the city is a vital visual environment.

For one thing, Sholis wants to put the street back into street photography. His show is keenly aware that capturing the urban scene means beginning with its infrastructure. It was instructive to see Sholis’s “Eyes on the Street” in the context of his first smaller show at the museum, an exhibition of a dozen or so mid-nineteenth century photographs of Paris by Eduoard Baldus. Baldus’s Paris is a collection of formal public buildings, seen from a distance, dominating streets that display plenty of signs of human presence but virtually no actual people. The inhabitants of Paris seem to have disappeared into cool, shaded doorways or must be sitting in the thousands of offices behind all those windows, some closed and some open, that interrupt the walls of the monumental buildings. Baldus’s Paris is a city waiting for the eye and hand of the Impressionists. Who knows what we might have seen along the Seine by night? But by day, the chief sign of human activity is construction. Baldus’s Paris is a city that is constantly self-revising. His pictures of Notre Dame show it being repaired and refurbished. Cluttered with debris and building materials, the cathedral is an active construction site and we experience it the same way many us experience city infrastructure today: we see a mess of rock, timber, and tools without any sign of the workers using them.

Olivo Barbieri’s work makes even more sense in the context of Baldus. From a distance—his pictures are taken from helicopters—he sees buildings and streets filled with traffic, the patterns of human commerce and movement. In his “site specific__Shanghai 04 #2” (2004), the old city is being torn down to make way for the new. The new city is sleek glass and steel and organically curved concrete. The only thing to human scale is the rubble of the low-rise brick buildings. There is something cool to the point of chilly in Barbieri’s work; it was not easy to tell what his attitude was towards the considerable amount of capital it takes to make a contemporary city’s inhabitable spaces. In “site specific__San Francisco 08 #4” (2008), we hover above an urban subdivision. We see three tiny cars on a twisting ribbon of brick road as they pass by the gleaming surfaces of small and expensive spaces to live. Not having an architect’s understanding of how component spaces are integrated to make city life possible, it was not clear to me of what this was a specimen.

By contrast, Mark Lewis’s eight-minute video “Beirut” (2011) was a fabulously lyric exploration of how people personalize urban space. We see through the camera’s eye as it walks down a rather glum and quiet street, passing the Princess Diana Hotel and Esquire Books (“Stationery and Oriental Articles”); this is the part of town, perhaps, for the least well-heeled tourists. There are shops without shopkeepers and outdoor tables without waiters. There is an air conditioner in every window and bundles of exposed wires everywhere; a good electrical contractor could make a fortune here. And then the first of several remarkable things happens: looking up at the façade of yet another hotel, we start to levitate. From that moment on, it seems to me, our eye is no longer objective but highly idiosyncratic and its own way, deeply personal. We float up some ten stories to the roof of the Napoleon Hotel, where we poke around. There is an open door with some cloth bundled inside, but it seems dreary rather than sinister; Lewis’s Beirut is not for those who can’t see beauty in the patterns of rust stains and peeling paint. Up above the roof, we nose about, taking in the distant skyline and even peek over the edge to the street below. And then another utterly remarkable thing happens. The migrating camera’s eye ends up on a peaceful patio with plants, chairs, wicker sofas under umbrellas large enough to provide shade on a wholesale level, and up a short flight of stairs to a tiny pool, where a woman is swimming laps. Three, maybe four strokes, then turn, three, maybe four strokes, then turn again, over and over. Both the photographer and the photographed have found ways to personalize urban space, to be both energetic and dreamy, and flesh out the skeleton of infrastructure.

Jennifer West is also interested in humanizing architectural space. Her piece has an impossibly long though completely descriptive title that can be abbreviated to “One Mile Film…,” taken on New York City’s High Line park. She took movies of ordinary urban adventures—especially rooftop frolics—and then taped 5280 edited feet of 35-mm film to the elevated sidewalk and exposed it, for almost one full day, to all the things that, we are told, some 11,500 visitors could think to do to the film within the limits of being more or less legal. They marked it in almost every conceivable way—drawing on it, spitting on it, walking on it, writing on it, and running over it with baby carriages. Though the people did not get to point the camera in the first place, when it came to ornamenting and defacing the exposed mile of film (it would take just under an hour to watch it all), they did a great job. Apparently, you can crowdsource your art. But the collaboration between the named artist and her thousands of unnamed collaborators produced a vivid and hallucinatory vision of the city.

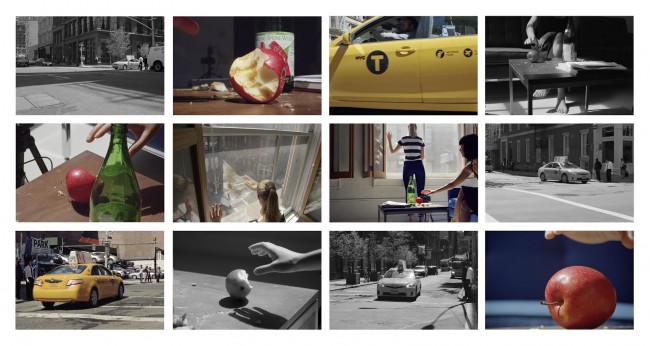

In place of the wealth of the spontaneous drama that had characterized traditional street photography, this show’s artists tend to favor what Sholis calls more “deliberative strategies” towards capturing—or creating—narrative. Paul Graham works by taking “sibling photographs” a few seconds apart to imply miniature stories. In the two pictures that make up “Fulton Street, 11th November 2009, 11.29.10 am,” a woman is walking and then, having apparently fallen, is about to helped up by passersby. There is something monumental, almost sculptural, about the groups of figures, and the lighting, though virtually unchanged between the two images, works very differently because the figures have all changed their exposure to it. I found myself wondering to what extent the pair was a documentary work or something staged. Though there is plenty of room for either—or both—it made a difference to me whether I should think that I was looking at Cartier-Bresson or Gregory Crewdson. By contrast, Barbara Probst’s works are clearly elaborately staged. She sets up as many as twelve cameras rigged to take their pictures at the same moment. In “Exposure #106: N.Y.C., Broome & Crosby Streets, 04.17.13, 2:29 p.m.” (2013), one woman in a well-lit room reaches for a partly-eaten apple while a second woman looks out the window towards the street, where a yellow cab is passing. Though all twelve pictures are simultaneous, it is hard, as Sholis notes, not to construct narrative sequences out of them. From one angle, we see the apple as if it had never been touched, while another angle emphasizes its partly eaten nature. In one picture, the yellow cab, pulled up at a corner, seems to have just come to a halt while from another angle, we feel it ready to cross through the intersection and continue on its way. It seems inescapable to wonder about the relationship between the women and, for that matter, the relationship between the women and the cab.

Barbara Probst, Exposure #106: N.Y.C., Broome & Crosby Streets, 04.17.13, 2:29 p.m. (2013). Courtesy of the artist and Murray Guy, New York.

There is a forensic quality to Probst’s sequences. In “Exposure #14: N.Y.C., 53rd Street and Park Avenue, 11.25.02, 1:30 p.m.” (2002), several walking figures are about to intersect. Which is the one we should foreground? Which one matters? The one with the red beret? The one who, from a slightly different angle, is crossing slightly in front of him? There is a quality of surveillance to this intriguing picture—are these people spies passing a stolen thumb drive from one to other or are they total strangers?—and we could be characters in Homeland trying to decipher the clues. In the third of the sequence’s three frames, we are further back from the scene and see a young couple who has seen the camera set up and are smiling and posing for it. Surely they aren’t working for the same spy runner…or are they? Probst’s work is an energizing exploration of how our visual experience has trained us to take point of view and use it to make stories.

But as everything about this show makes clear, the camera’s point of view on the street cannot be taken for a neutral presence. Sholis writes that “today, discussion of cameras in public spaces often concentrates on issues of surveillance, personal privacy, and first-amendment rights.” The monumental portraits of Philip-Lorca DiCorcia—if indeed portraiture is what they are—are in some ways the central works in the show. The photographer rigged up a photo-taking machine on the street and as people walked through its zone of focus, they triggered a strobe light and a picture was taken without their awareness or permission. They are elegant and dignified; the figures caught in them have the almost hyperbolic dignity more associated with, say, the studio work of Yousuf Karsh, than the fleeting candids of the street tradition. But the subject of one of these pictures found his image made public somewhere and sued DiCorcia. Both Sholis’s essay and the wall labels at the Museum tell this story, which is clearly as important as the pictures themselves. What is the legal status of a picture taken without the subject’s legal consent? Does walking down the street compromise an individual’s claims to privacy? Who owns the representations of things that a camera can capture? It was interesting in this context that the exhibition itself did not permit photography. Does an artist’s copyright trump the rights of the original subject of the photograph? Legally, apparently it does, by the way, at least under certain circumstances. In 2005, a judge ruled that since the pictures had artistic purposes rather than commercial ones, the artist’s rights took priority. In the age of Snowden and the ever-widening distrust of the N.S.A., one wonders if today, the same decision would get made. And what would happen to street photography if that decision went the other way?

Jill Magid explicitly takes on this issue in her 18-minute video “Trust” (2004), which explores the nature of our observed public life in a culture like that in the UK where CCTVs are everywhere. Wearing a red raincoat so she can be easily picked out, Magid resolutely closed her eyes and kept them closed while the cheery operators of the CCTV cameras in a busy thoroughfare in Liverpool communicated with her via earphone and directed her on a brief, blurry, completely surveiled walkabout. Sometimes, the camera just catches her as she disappears in a larger crowd. Sometimes, it seems to ogle her. She walks, braving encounters with people of all ages who have no idea that she is part of a work of art or, for that matter, that they are now too. “Stop,” the voice of the CCTV operator tells her, “you’re veering to the left all the time.” She tries unsuccessfully to walk a straight line with her eyes closed on a city street. “You’re getting strange looks.” Only one figure in the crowd is wearing a red raincoat; it is hard not to think of her as a target. It is hard sometimes not to think that in the next moment, we will witness the result of a Predator missile having been launched. Magid noted how strong a bond of trust she formed with the voice on which she was so dependent for those 18 minutes, but it also hard not to think of the possibility of Stockholm Syndrome, or perhaps the similar set up of the movie “Phone Booth” (2002), where Colin Farrell takes commands from his unseen tormentor Kiefer Sutherland. “Look at the camera for me,” she is told, and she does. Magid’s piece is both brilliant and creepy, especially as we ourselves cannot feel the growing and warm bond of trust she describes. At the end, the voice releases her: “Open your eyes. Hi. How are you? Good morning.” Time to call in the police—but wait: the CCTV operators are the police.

For me, the show’s thought-provoking, elegant, and almost totally delightful masterpiece was James Nares’s “Street” (2012), a 61-minute video edited down from some sixteen hours of high speed, high definition film taken as he cruised the streets of New York City. It explores the world of the crowds on the street without ever having to exactly slow down to become part of them. In intensely detailed slow-motion, people make their ways along the streets, slowing down at intersections where they form into spontaneous groups as elegant and powerful as Rodin sculptures. It is amazing how many different directions a small group of people will be looking in while waiting for the light to change. In front of a store, one man blows soap bubbles that float with indescribable elegance in the same direction as Nares’s car over garbage and filth. A pigeon chuffs by in slow motion, negotiating a landing to dine on trash; no pigeon has ever looked so good before.

It is probably hard to sneak past crowds of New Yorkers with a substantial camera pointing at them. One man lifts his arm to cover his face. Is he tired? Hot? In need of some privacy? On the run? Another guy sneaks a look at the car and camera, just moving his eyes, not his head. We pass a playground and a child hits a baseball which moves so slowly it’s hard to imagine how anyone ever gets to base. A guy passes a public garbage can in his walk and gives it a quick check-out: just looking. And people look at their cell phones with a fixity and single-mindedness that slow motion fully captures.

The Nares piece, at least while I was at the Museum, was a huge crowd pleaser. Behind me, someone said “No one looks happy,” but I could not disagree more. I can tell you that New Yorkers are not, in fact, as well-dressed as people say, but on the other hand, they are extraordinarily self-possessed, and many, many of them seemed to be feeling joy. In one remarkable sequence, a child runs at full tilt, though in hyperbolically slow motion, in the same direction as the car. We follow him and feel the full exuberance of his living the better part of his life outdoors, in the street. In some ways, the Nares piece was the true inheritor of the traditional work of the street photographer, and it did it with elegance and generosity. Everything I saw while I watched had at least as much compassion for the faces in the crowd as Winogrand showed, and maybe even more allied to the humanism of Helen Levitt. These streets are well worth watching.