I. Images For A Better World: Ellen Jean PRICE, Visual Artist

Ellen Jean Price was born in New York City and grew up in Queens. She studied life drawing at the Art Students League and enrolled in Hunter College before completing her BA in Art at Brooklyn College. She then went on to earn an MFA degree in Printmaking (1986) from Indiana University in Bloomington, Indiana. Price is currently a Professor of Art at Miami University in Oxford, Ohio, where she teaches printmaking and serves as Director of the Studio MFA Graduate Program.

Price is an active participant in the printmaking community. She presented a paper on “The Cultural Politics of Kara Walker” at the IMPACT conference in Cape Town, South Africa, and at the Southern Graphics Council conference at Rutgers University. She also gave a talk titled “From Broadsides to Tabloids” at the Mid-America Print Council conference in Lincoln, Nebraska, and authored an article for the Winter 2012 issue of the Mid-America Print Council Journal.

In Price’s artwork, recurring allusions to history, memory, fragmentation and dissolution unite apparently differing subject matters. Her creative work was recognized with Ohio Arts Council (OAC) Individual Excellence Awards in 1996, 2001 and 2009 as well as by a 1998 Cincinnati Summerfair Artist Award. Her most recent OAC recognition was for a series of ink transfer lithographs based on cropped views of her family photographs.

Price’s prints are included in the permanent collection of the Cincinnati Art Museum and the Dayton Art Institute.

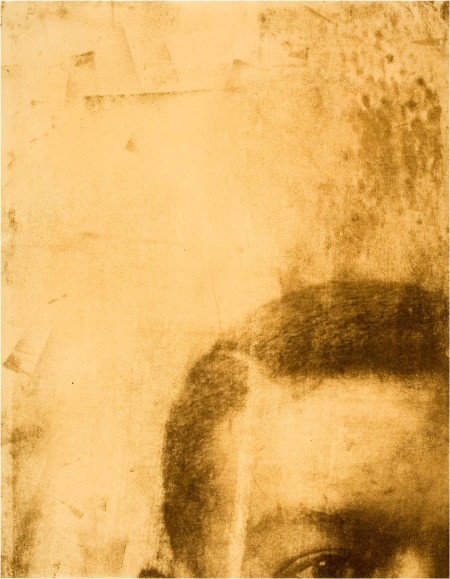

“Section” is from a series of ink transfer monoprints based on a collection of Price’s family photographs dating from the early 20th century. The photographs served as the catalyst for the print series as well as its source material. Taken with large format cameras, many of them were from photographic studios, with the subjects posing and looking directly into the camera. Price scanned, enlarged and cropped the original photograph, a process which resulted in the close, focused examination of a small section of the subject. The dislocation and fragmentation of the original image seemed apt on several levels, the fragmentation of the image relating to the small slice of the subjects’ life captured by the camera in the photographic process, and similarly, the partial view of the countenance relating to the incomplete knowledge of the original portrait subject.

In the broadest sense, the content of Price’s work centers around personal identity. In an exhibition statement she wrote: “As the child of a bi-racial marriage, the subject of race was both non-existent and ever present. Growing up in ethnicity-conscious Queens, New York, during the 1960’s, I was frequently asked the question, “What are you?” As an individual whose African-American descent is not obvious, the space between what is revealed and what is hidden is familiar psychic territory and drives my absorption with the portraits of earlier generations. The portrait series are a result of my search to locate my identity between the revealed and the hidden and acknowledge the imperceptible pull the past exerts on the present.”

The subject for the ink transfer lithograph “Tuxedo” is Price’s grandfather, Rhodes Price. Rhodes Price was employed as a railroad waiter and porter and was a member of the Brotherhood of Sleeping Car Porters, which held a unique place in history as a black- led labor organization, headed by A. Phillip Randolph. Price was interested in the potential ambiguity of the tuxedo shirt front as both the traditional outfit of the butler as well as of the wealthy client.

“Edgecombe” contains two cropped images with an empty field of pale color. Edgecombe Avenue was the name of the street in Harlem where Price’s father grew up, and where her family owned a brownstone since 1925. While visiting her grandmother Price encountered some examples of the family photographs which would later come into her possession. Taking these photographs from a private setting to a public discourse was part of a long period of development as she had studied them for years, and always wanted to engage the works in a creative process. Commenting about her undertaking, Price wrote: “The relocation of my relatives’ images from the private sphere of a family album to the public sphere of a gallery wall echoes in the space between public and private, known and unknown.”

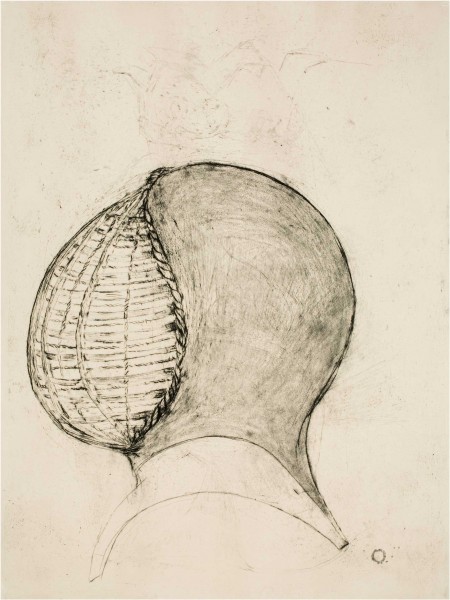

“Basinet” and “Tournament Helmet” are both drypoint prints, created by drawing with a sharpened stylus on a metal zinc plate. Ink is then rubbed into the lines, and the print is printed as an etching.

The depiction of the helmets, as representative of the technology of warfare from some 500 years ago, was influenced by world events, primarily the war in Iraq. At the time Price did these prints, the war had gone on for several years, with no end in sight. The helmets which seem antique and quaint, call however into question humankind’s long record of state sponsored combat. Even though human technology has evolved drastically from the period of the manufacture of these artifacts, humans have not evolved enough to stop killing each other through state sponsored, organized warfare.

Price’s interest in the helmet imagery first began with a fascination in the extensive armor collection at the Metropolitan Museum of Art. A concurrent interest in the history of printed images, early engraving and broadsheet illustration brought her to the exploration of the subject matter for these images.

“Pull” is the most recent of Price’s images presented here. Price is currently working on a series of ink transfer monoprints in which uprooted plants and flattened leaves are described by contour lines and diaphanous shapes. With the contrast of line and shape, the print draws on the relationship between varying languages of depiction as well as the tensions between flatness and spatial illusion. The finished image is the result of multiple layers of ink accumulated on the membrane- like quality of the very thin mulberry paper being used. While it may be difficult, and potentially limiting, to define a one to one metaphoric relationship, the uprooted plant forms reference ageing, dissolution, loss and decay.

II. Words For A Better World: Angela DERRICK, Literary Artist

Cincinnati poet/writer Angela Derrick has a love of words that began when she learned to read. This, however, did not happen at Mass Fields School in Massachusetts where she attended grade school, a school which, like many others back in the early 1970s, had wholeheartedly embraced the “Whole Word” reading method, a method that focused on memorization rather than phonics. It was the chance occurrence of a reading specialist moving into the house next door and who tutored her in phonics for more than two years who actually taught her how to read. Where the “Whole Word” method failed so spectacularly, phonics saved the day and opened the door to a world of wonder.

Books then became Derrick’s passport. One of her fondest childhood memories is of the snowy afternoon when her afterschool sitter, Mrs. D’Angelo, sent her outside with the admonishment: “Little girls should be sliding down snow banks with rosy cheeks!” Rather than play in the snow, Derrick slipped her Nancy Drew mystery under her coat and retired to her enclosed back porch to continue reading.

Early on, Derrick knew that she wanted to write. During a recent move, she came across her junior high school yearbook, and flipping through it, read aloud to her sons one of her classmate’s inscriptions from more than thirty years ago: “To Angela, a girl who will one day be a writer.” An avid reader of all genres, both fiction and non-fiction, and of whatever catches her fancy, Derrick entirely embraces author Stephen King’s philosophy that a writer also has to read.

Derrick began writing poetry and stories at a young age. While attending college at the University of Cincinnati, she enrolled, during her freshman year, in Creative Writing classes. After several terms, she quickly realized, however, that the effect of the creative writing classes on her was contradictory, leading instead to a self-censoring of her writing. She stopped then taking the classes and, with curiosity, started attending classes at Women Writing for (a) Change, an organization founded by former English teacher Mary Pierce Brosmer. W.W.f. (a )C. which offered a nurturing and supportive writing community for women only, boosted her self confidence and unleashed her personal writing energy. She attends writing classes there up to this day.

It was Derrick’s love of books that sparked her interest in the fight for the abolition of the Death Penalty. Watching the evening news one day late September 2005, a segment about California Death Row inmate Stanley Tookie Williams grabbed her attention. Williams, a former gang leader and co-founder of the Crips street gang, had co-written a series of books with journalist Barbara Becnel, all with the noble purpose of educating youth on the danger of gangs. Derrick began to follow his case as many prominent people and in particular the non-profit agency “Campaign to End the Death Penalty” spoke up urging then Governor Schwarzenegger to commute his December 13th execution into a life sentence. Feeling certain that the execution would be stayed, Derrick’s faith and belief in justice was shaken when the execution was carried out anyway. At that point she decided to write to a death row inmate and sent an earnest letter to California death row inmate Kevin Cooper, in which she naively offered to be his pen pal and to send him books. She was taken aback when she received his following response: “As to your offer to be my papal, I must respectfully decline, as I have everything I want and need. However, there is someone who wants and needs a friend such as yourself. I urge you to find him.” Being somewhat literal minded, Derrick took Kevin Cooper’s words to heart and mailed her first letter to death row inmate Jason Derrick on December 31, 2005. In 2009, she and Jason were married by a preacher in the Death Row Visiting Park.

Many of Derrick’s poems are centered on the theme of prison and what it is like to have a loved one incarcerated. In 2014 she self-published Melancholy Is When I Leave You, a collection of poems written over the previous nine years. (http://www.amazon.com/Melancholy-When-Leave-You-Prisoner/dp/1502571862/ref=sr_1_1?ie=UTF8&qid=1428768807&sr=8-1&keywords=Angela+Derrick). She is also currently working on her first novel.

Derrick is a graduate of the College of Mount St. Joseph, with a BA degree in both Paralegal Studies and English. She lives in Cincinnati and has five sons and one grandson.

1. Of all the poems Angela Derrick has written, “Who We Are” is her favorite. She wrote it back in 2008 while sitting in her car waiting to line up for a visit to her incarcerated husband. Every time she rereads it, a chill runs up her spine. The rhythm of the poem feels to her just like her process of entering the prison.

Who We Are

We are

friends, wives, lovers, mothers, daughters,

sisters, cousins, aunts.

We are the loved ones.

We might be you.

We come

from across the street, across town,

two towns over, out of state,

across the ocean.

We travel millions of miles.

We wait – in our cars,

In line, at the gate, inside the gate,

At the door, at the table.

We wait. Period.

Docily we follow instructions:

Line up here

Sign this

Scan your hand

Hold out your arms

Spread your legs

Shoes off

Lift your feet

List your jewelry

Shake out your bra

Count your money

Count your blessings

You get to leave.

We pass through

Eleven gates

Razor wire

Barb wire fences

Metal bars

Security doors

Stun guns

Only five through the gate

at a time

to the park that isn’t a park at all.

We are the other half,

The unseen and unheard

Prison population,

Living in the land of the free,

but incarcerated nonetheless.

2. A pantoum is an ancient Malaysian poetry form in which lines are repeated in a different order throughout. As the lines are repeated at different places throughout, the meanings shift to create the poem. In “Pantoum Terrarium” Derrick aimed at painting a picture with words of the death row visiting park.

Pantoum Terrarium

In the terrarium with twenty-six metal tables planted

randomly around a barren garden

guards are scattered like dandelions and

orange and white flowers are searching for the sun.

Randomly around a barren garden

hand in hand marching down the path

orange and white flowers are searching for the sun

moving back and forth, back and forth.

Hand in hand marching down the path

guards are scattered like dandelions and

moving back and forth, back and forth

in the terrarium with twenty-six metal tables planted.

3. All of Derrick’s poetry comes directly from her experiences. She uses language to evoke the things she experiences, her goal being to take her reader directly into her experiences by engaging the senses. The occurrence in her poem “The Ring” happened as she has written about it.

The Ring

I walked out right behind her-

felt the heavy vibration of the

big metal door slam with

a resounding thud, the

breeze of her whipping by

me as she turned towards

the wall-sized double glass

of the guard’s booth.

She knocked and

waved her hand-

gestured at the large

gold ring she wore.

While visiting her husband,

she had worn his ring.

Caught up in the moment

of saying goodbye, she

had forgotten to give it back.

How very natural it is to put

on something of your beloved’s!

Haven’t you at one time or another

put on your dear one’s shirt?

Luxuriated in his manly sweaty essence?

I bet you have.

I bet you know exactly what

I’m talking about.

I heard the unforgiving words of the

guard, the menacing threat that

they were going to lose their visits-

saw her composure vanish

instantaneously- replaced

with heart-wrenching sobs-

her whole body shaking.

I wanted to speak up- an

innocent mistake, I would

say- but I held my tongue,

knowing better than to draw

attention to myself.

I later learned that they had

not lost their visits after all

and I was glad-

the following year I heard that her

husband had died from cancer.

4. In “Petting Zoo” Derrick captures what it is like to have an incarcerated spouse, and how even the most innocent gestures can be considered suspect behind prison walls.

Petting Zoo

Sitting with my husband,

both our arms on the tabletop,

I absentmindedly run my

hand across his forearm,

an intimate gesture to be sure,

but certainly outside that

which could be classified

as inappropriate.

Sergeant X, walking throughout

the room, pauses nearby, looks

pointedly at me, rocks

back and forth on the balls

of his feet, says:

No petting the inmates.

Startled I stare right back at him,

keep running my hand lightly across

my husband’s arm and respond:

Why Sergeant, are you calling

my husband an animal?

I stare, unblinking until he breaks

away from my gaze and moves on,

my hand lingering on my husband’s arm.

5. There are many rules for getting married in prison. The poem “Wedding Day” speaks of Derrick’s own personal experience.

Wedding Day

The prison said do not wear white.

You will be turned away.

This is a low key wedding.

She said Oh! You are

waiting for me-

that’s a first!

The pastor said do

you take this

man/woman

to be your lawfully

wedded

husband/wife-

to have and

to hold in

sickness/health-

for richer/poorer-

in

good times/bad-

so long

as you both

shall live?

He said I do.

She said I do,

The pastor said

I now Pronounce

you

husband/wife.

You may kiss

your bride.

The camera man

said it came out

blurry- your

first kiss.

I can retake it.

She said they’re

all coming out

blurry

The camera man

winked and grinned.

The guard said

If you two don’t

stop all that

kissing- I’ll

end the visit.

He said I’ve

heard that

married men

live longer.

The sergeant said

Master Count- the

Visiting Park

is now closed.

She said I love you.

He said I love you.

The guard said

It’s time to go.

She slowly walked

back to her car and

drove away a

married woman.

–Saad Ghosn