While many large American arts institutions, such as Cincinnati Music Hall and the Cincinnati Art Museum, were founded in the 19th century, it wasn’t until just before and after World War II when such cultural institutions were planted in many smaller cities, like Springfield, Ohio.

For so young an institution, the Springfield Museum of Art has an attractive permanent collection of 19th and 20th century American art. It also features a robust rotation of engaging exhibitions throughout the year.

Particularly after World War II, “there was a flowering of the arts in smaller cities,” says Ann Fortescue, executive director of the Springfield museum the past four years.

After the major sowing of metropolitan museums East of the Mississippi during the 1870s and 1880s, “there was another wave that happened a little bit before, but after World War II in particular,” says Fortescue, as there was a growing emphasis on the arts as the concept of leisure time and weekends burgeoned across the post-war nation.

“And there also was this very strong push societally for education and cultural appreciation,” she says. “That spurred many communities to develop either art centers or places where in particular, children, could be exposed to, and receive instruction in the arts.”

In Springfield, the Springfield Art Association was formed in 1946. Area businesses that supported the cause, and later leased galleries, hosted the first visual-arts exhibitions. During the early 1950s, the association started offering art classes for both children and adults, and finally, in 1967, the earliest part of what then was called the Springfield Art Center, rose from the ground.

That original space was doubled in 1974, and three years later the museum received a collection of 19th and 20th century American and European artworks, leading the institution to focus on a permanent collection. By 1989 the center became the Springfield Museum of Art. A $3.85-million capital campaign increased the facility to today’s size, adding 15,000 square feet of space to the existing 20,000. The facility’s today has a total of more than 6,700 square feet of exhibition space.

“The organization’s growth spurt mirrored both local as well as national interest in the arts,” Fortescue says. “In the early-to-mid ‘90s there was a real growth spurt among museums nationally. Many museums added additions or built whole new buildings, and part of it was the financial climate was favorable to capital projects, and there was a recognition that informal education is critical to a well-rounded individual.”

Fortescue still sees a lot of growth potential for the museum.

“One of the things that attracted it to me right away was the quality of the collection,” she says. “It’s a really remarkable collection of American art.

“While the collection is not deep in one particular area, it is representative, from the early Republic to the present,” she says. “And the work is American art with a very strong focus on Ohio artists. And I see that as being one of our real strengths.”

She also was attracted by how underutilized the museum was, mainly because people weren’t aware of it.

“This is an attractive challenge for me – it’s something that I really enjoy doing, engaging the community in the museum,” she adds.

Still in Springfield today, Fortescue can tell people, “There’s an art museum in your community,” and people will express surprise or show vague awareness of the center that’s tucked in a ravine near downtown.

She enjoys the small museum’s ability to quickly assemble exhibitions.

“One of the great benefits of having a small museum is that our nimbleness enables us to do things that at a larger museum it would take much more time,” she says. And it’s not that we’re any less intentional or less deliberative. It’s just simply a matter of size. There are three of us here on staff, and it’s much easier for us to have a coffee klatch or a copier-room conversation, and then go make it happen.”

The museum typically has several exhibits running simultaneously. During the winter, one standout show was, “Painting Ohio Prairies: A Year in the Life,” an Ohio Plein Air Society exhibition that was a delightful look at the diversity of Ohio landscapes from prairies alone, through various seasons, times of day, and moods.

The show filled the spacious and remarkable McGregor gallery, a curved area filled with soft light.

At the same time, other exhibits included Point of View, Landscapes from the Permanent Collection by painters of the Hudson River school and others; Compelled: Folk Art & Vision, which offered works from the folk art and outsider traditions; Portraiture Through Time, from the permanent collection; Drawn from Life, other selections from the permanent collection; and the Wittenberg University Senior Thesis Winter Show.

Fortescue’s emphasis on outreach is evident in the Gallery Guides produced by Curator of Education and Exhibitions Deb Housh. The guides, some of them several pages long, are accessible to non-artists and include brightly colored images of several works.

Attendance is rising. In 2014, the museum in the city of about 60,000 had more than 17,000 visitors.

“We’re fortunate,” Fortescue says. “We’re sitting in a community that’s rich with artists, and so one of the ways that we engage our audience is engaging local artists. We still do an annual juried members exhibition, and that takes place in the McGregor gallery. So this absolutely magnificent gallery gets filled with works of art created by our members who are artists.”

The museum is the only one in Ohio officially affiliated with the Smithsonian Institution. According to the museum’s website, “the distinction celebrates the museum’s adherence to best practices and its exemplary permanent collection, which features artists such as Berenice Abbott, George Bellows and A.T. Bricher.”

The affiliation lets the museum display works from the Smithsonian’s collection.

Meanwhile, the building that houses the museum officially is called “the Springfield Center for the Arts at Wittenberg University.” The school is just up the hill.

“A couple of years before I was hired the museum sold the building to Wittenberg University,” Fortescue explains. “At the time, Wittenberg was considering building an arts complex, and through conversations with the museum, decided that rather than building a new building, that purchasing this building, with an already operating art museum in it, and using the other space, would be more cost-effective for the university.”

The university president who had that vision left Wittenberg, and the new president has been focused on other issues, so a more complete integration has been on hold. University faculty and sometimes students have exhibits a couple times a year, and students intern at the museum.

“I see our partnership opportunities and our partnership with the university continuing to grow and evolve,” Fortescue says.

Coming in August

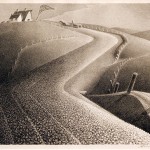

From August until January of 2016, the museum will present a 75-painting exhibit of statewide interest, The Best of Ohio’s Regionalists, 1915-1950, assembled by guest curator Tim Keny.

The show “will bring together Ohio’s master artists in this genre such as George Bellows, Edna Boise Hopkins and James Hopkins, William Sommer, Clarence Carter, and Clyde Singer, with their equally well-versed yet not fully celebrated col-leagues including Emerson Burkhart, Yeteve Smith, Harriet Kirkpatrick, and Robert Chadeayne,” according to a museum news release.

Here’s more of what the release has to say: “This exhibition broadens our perception of Regionalism, which occurred simultaneously with the American Scene movement and is often more closely associated with the Midwest, west of Ohio. That Regionalism is closely linked with the lithographs and paintings of Thomas Hart Benton, John Stuart Curry, and Grant Wood, which is firmly rooted in the agrarian lifestyle of that region, sometimes tinged with wry humor about America’s puritanical roots. Ohio’s Regionalism, because of the rich diversity of its economy – from agriculture to heavy industry – and its extraordinary blend of different cultures, became a fertile ‘crossroads’ of style, subjects and social commentary that belies Regionalism’s more simplified, grassroots connotation.”

Springfield has many of the artists in its permanent collection, and also has a number of today’s Greater Cincinnati artists’ work in the collection as well.

–Mike Rutledge