Where are you from and where do you currently live?

I grew up in St. Louis, Missouri. I went to graduate school at the University of Iowa in Iowa City, and for the past four years I’ve split my time between the United States and Doha, Qatar.

Did you create Donkey Lady and Other Tales from the Arabian Gulf as a result of your time in Qatar? Could you describe this series and ways in which living between two very different parts of the world influences your subject matter?

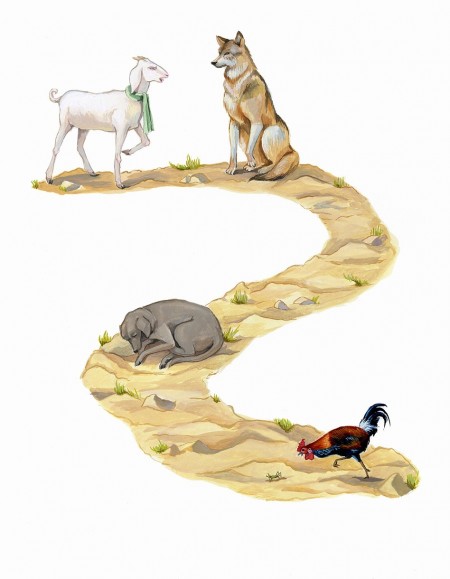

The Donkey Lady series is actually a set of illustrations I made for a collaborative book project between Qatar University and Virginia Commonwealth University in Qatar. It’s a compilation of traditional Gulf folk tales that were collected and illustrated by students and faculty, and published by Berkshire Academic Press. In terms of my personal work, I tend to avoid directly referencing my experiences in Qatar. With a history of Orientalism and Western colonialism in this part of the world, I am cautious about making work related to the culture or politics of the country. But I would be surprised if my daily visual observations of life here haven’t influenced my work in subtle, unconscious ways.

Did art play an important role in your childhood?

My father is an artist and a painting professor, so I spent a lot of time around art as a kid. I was constantly drawing throughout my childhood. I liked to write stories and illustrate them, so I think that love of narrative has carried over into my professional work as an adult.

Did you have one of those “aha!” moments when you knew you wanted to become an artist?

Not really an “aha” moment—art was always on the table for me as a career choice, although I was also interested in writing, fashion, and gender studies. There was a moment in college where I had to choose a study path, but I feel like those other interests have made their way into my work.

I’m sure your work prompts this type of question on a regular basis, but I can’t help but ask if feminism plays a significant role in the themes / subject matter you depict?

Yes, absolutely. When I was around fifteen, my mother gave me a book called Reviving Ophelia: Saving the Selves of Adolescent Girls by Mary Pipher. This book was so important to me, because it described real case studies of girls my age as they dealt with depression, self-mutilation, sexual violence, and social pressure, as I at the same time was transitioning out of childhood and trying to come to grips with the harsh realities of womanhood in a sexist culture. I think my paintings tap into that anxiety. In my teenage and college years I began reading feminist works of fiction like The Handmaid’s Tale by Margaret Atwood and The Yellow Wallpaper by Charlotte Perkins Gilman. Later in graduate school I was introduced to the writing of feminist scholars like bell hooks and Judith Butler, whose ideas have also played a part in the development of my work.

In reading hooks and Butler, were there particular ideas that strongly resonated with you in the context of your work?

I think their ideas have had more of a broad effect on my understanding of girlhood and how I reflect upon and reframe my own experiences, rather than being directly depicted in the paintings. But specifically, I would say that key concepts like intersectionality, the oppositional gaze, and gender performativity have changed the way I think about the world, and are present in my mind when I’m making choices about what to paint.

Could you describe your process, how your imagery is developed? Do you maintain a set studio schedule? Do you keep a sketchbook?

I carry a little Moleskine with me for recording ideas. I am a bit of a magpie when it comes to collecting images, and am always on the lookout for something that I can use in a painting. I’ve basically compiled a library of source material over the years, which I have organized into categories that I can pull from depending on the direction I want to take. Usually I find these images in photography archives, school textbooks, Victorian postcards, and other printed matter. I look for slightly odd things that pique my curiosity—a pose or activity, maybe an article of clothing or an interesting setting. In a gouache sketch, I piece together these found images with other elements (either imagined or from memory), and place figures within the scene like actors in a play.

I appreciate the narrative quality of your imagery and the way in which you create compelling scenes that seem both solemn and whimsical. Maybe this is solely my perception, but can you speak to the tone of your work? How do you want the viewer to viscerally interpret the images?

I like my paintings to seem sweet and playful at first glance, but as you look closer they take on a more sinister quality. I want the viewer to be slightly unnerved. There is a free and imaginative spark in girls that is routinely met by the outside world with attempts to stifle, to assimilate, to crush and to mold. There is curiosity and joy in girlhood, but there are also nightmares. And girls themselves, though typically regarded as gentle innocents, are also capable of dark thoughts and actions, as much as they are of love and virtue.

There’s a woman in a black Victorian-style dress and veil who is featured in two different works—Little Lamb, I’ll Tell Thee 2013 and Procession 2012. Does she have a specific symbolic meaning? Since she’s accompanied by girls wearing matching blue dresses, I wondered about the role of reoccurring characters / clothing and how they function within your work?

Clothing plays a very important role in my work. In earlier paintings, the idea of the uniform was of interest to me as a metaphor for assimilation and gendered socialization. Gradually I began to introduce other types of clothing, like patterned dresses, animal costumes, white baptismal / bridal shifts, and black funeral attire, all of which represent different modes of identity. As for the veiled woman, she is in mourning. She is shrouded and faceless, but watchful. To me she is the dark mystery of adulthood from the point of view of an adolescent girl; she is fear and sadness, but she is also authority.

I’m intrigued by this faceless representation of “the dark mystery of adulthood,” because as I read your response, a few women from my own childhood immediately came to mind. Did you want to represent this idea of adulthood from a girl’s perspective and then look for a symbol to serve this function? Or did you first discover imagery that prompted the idea? I guess I’m asking a “which came first…?” question, but curious to know more about your process, especially since you mentioned your library of source material.

I remember womanhood seeming curious and exciting to me as a child, but also terrifying in its obscurity and inevitability. And now that I have reached adulthood, I feel a longing for that childhood innocence and freedom I’ve lost. When I came across these eerie images of black-cloaked women in mourning while researching Victorian photography, it struck me as a perfect metaphor to encapsulate that feeling of fear and mystery from one perspective, and deep sorrow from the other. So I didn’t really go searching for a symbolic representation of the idea, rather I stumbled across it.

Your characters always appear to be caught in a moment of action and I notice on your resume that your work was included in a comic art exhibition, Bam! Pow! Zap! Comic Art and Storyboarding, Foundry Art Centre, St. Charles, Missouri. Sequential art seems like a natural extension of your imagery. Have you developed any of your paintings / drawings into a graphic novel, comic book, or animated film, etc…?

For years I’ve been working on-and-off on a graphic novel that features some of the themes in my paintings, but haven’t gotten to a point where I am satisfied with it. I’ve had thoughts about other ways to experiment with more sequential media, but none of it has come to fruition at this point.

Who are some of your favorite artists? Are there any in particular that have influenced the direction of your work?

There are several mid-century women Surrealists that I love: Leonora Carrington, Remedios Varo, and Dorothea Tanning. Their paintings are so bizarre, and I like the way their female characters seem to be imbued with a sort of mystical power. Cindy Sherman is an early and important influence for me, as well as Balthus—I often use Balthus-like poses and compositions in my paintings, albeit from a completely flipped perspective regarding female adolescence. I look at fifteenth and sixteenth century Dutch and Flemish paintings for their beautiful treatment of faces and clothing, their poses, and iconography. I also really love Victorian to mid-century illustration, specifically children’s books, which I tend to borrow from stylistically.

I’m always interested in learning from other artists’ training and wondered if you had a particular teacher(s) who significantly impacted your artistic development? If so, could you describe how? Do you have advice to share with aspiring artists?

I had some really fantastic professors to guide me at the University of Iowa, who I credit with pushing me to develop my work conceptually. Although I can’t say that I had one specific mentor during this time, the direction my work has taken can be attributed to the time I spent with this diverse group of educators and artists. I also feel that having an artist as a father has had a great effect on me. While I never received any formal instruction from him, I’ve learned a lot by listening to him talk about painting. He’s always had a way of pointing out things around him that are interesting, especially observations of light and color, which I think has nurtured me to appreciate visual subtleties in my everyday world.

In terms of advice to aspiring artists, I would say that reading is one of the best things you can do. In addition to art-related texts, I think fiction is an incredibly valuable resource, as is any quality writing (science, philosophy, biographies, etc…). I definitely consider the time I spend reading to be part of my research.

–Kim Rae Taylor