In February, I attended what I thought was the opening of Graffiti and Street Art Museum (GASAM) among the warehouses of Houston’s East Downtown. Much-hyped in local media since the fall, the museum currently lives in a fairly average gallery space populated by bright canvasses and display cases of graffiti ephemera. At the event, a wall-sized projection showed spray painting in action, and a live DJ got the party going. Houstonians of all ages were present, from boomers nursing cans of Lone Star to the under-10 crowd dancing and laughing in the projected images. It had more of a block party vibe than anything else—all that was missing was barbecue.

It wasn’t the official opening, though—the space is still appointment-only. Gonzo 247, aka Mario Enrique Figueroa Jr., later explained to me that it was really more of an open house. He is the co-founder of the GASAM, along with his wife, Carolyn Casey-Figueroa. They do plan to open sometime this summer, as soon as staffing and other logistics can be settled, but Gonzo emphasizes his commitment to an organic process. “We don’t want to over-hype what we’re doing. We want to be sincere in our efforts—we’re not in a rush.” The same goes for the space: it’s not permanent. “This is an incubator for us; we’re testing out ideas here, and we’re hoping that this space is going to lead us toward our more permanent home. It’s sort of a fun trial-by-fire.”

I have to cop to being one of those with an overt focus on when it will open, like others who have interviewed him about the GASAM. I, like others, know it will be another artistic gem for our city, another feather for Houston’s already prestigious but too often overlooked artistic hat. A unique one, too: although graffiti being showcased in art galleries is not that new, the GASAM will be the first museum with this explicit graffiti focus in the country. But the co-directors’ approach is holistic, dependent on the needs of the art, space and community the museum will serve.

Piece painted on a car hood by Iranian brothers Icy and Sot, who currently live in Brooklyn. Photo by Jessica Almanza.

One thing you notice while talking to Gonzo, whose moniker is more inspired by the Muppet character than the journalism style, is that he’s on a long-term schedule. He speaks in terms of years, and isn’t afraid of missing a trend. That patience and work ethic is reflected in his personal history. His epiphany at a high school assembly would make a great set-up in his completely hypothetical biopic: the speaker asked the old motivational question, think of the one thing you love to do so much, you’re willing to do it for free—then do that professionally. “The thought of doing graffiti professionally blew my mind, because back then in 1990, graffiti was still considered illegal, gang-related vandalism,” Gonzo recalls. “Knowing that it was an uphill battle, I was inspired to say, okay, I know what’s ahead of me—I know what I have to fight to get to that long-term vision.”

It took a few years of knocking on gallery doors and scouring the yellow pages for art spaces—not to mention a few angry rejections and accusations of being a gang member—but finally one enthusiastic gallery saw the potential for Houston’s graffiti scene, and agreed to host an exhibition. That’s one of the historical events that the GASAM observes: “In 1993, we were able to curate Houston’s very first graffiti art exhibition: Bombs, Burners, Scribbles and Tags,” Gonzo says. “That was a turning point for graffiti in Houston. Nowadays people almost take those exhibitions for granted—but in ’93, it was revolutionary.” That gallery has since closed, but in 1993, Bombs, Burners Scribbles and Tags was the most well-attended opening they’d had to date.

By that time, he had also founded AerosolWarfare, which began as an international video zine incorporating all four elements of hip-hop—graffiti, emceeing, breakdancing and DJing—and is now its own independent studio fostering the talents of local and international artists. When I spoke with him at the museum, which is separate from AerosolWarfare but contains Gonzo-only studio space, he was still cleaning up the aftermath of creating a huge NCAA bracket that was displayed in various Houston venues. It had spilled out of his studio and into the lobby as he worked, likely listening to the same Run DMC or Eric B. and Rahim records he loved as a kid. During the interview, another visitor comes to check out the space as a potential event venue. The space’s liquid purpose is analogous to its diverse intentions and function.

Pieces of Houston’s graffiti history, with Gonzo in vintage Astros jersey. Photo by Jessica Almanza.

Intention is an important factor here. Doesn’t putting street art inside a building mar its intention? Gonzo is well aware of the dichotomy, having toed that line for the past twenty-some years. “Graffiti on its own is anti-authority,” he says, “so our situation is, how can we make something somewhat legitimate when this art form started off as illegitimate? Graffiti is meant to be outdoors. It’s meant to be in motion.” But, having created art in a wide variety of locations and environments, he doesn’t believe that it affects the art itself as much as one would think. “You can do the same amount of work with the same amount of intensity that you would on the side of the building.” If street art is a wild animal, he hopes the museum will be a beautiful, ethical zoo, where patrons can take it in at their own pace in an air-conditioned environment.

That being said, there’s always something special about seeing an animal in the wild, and one of the museum’s offerings is mural tours. “You absorb the artwork in in the context of the surroundings, the weather, the sky, the breeze, the rain, the shadows, the obstructions on the buildings, the windows, other graffiti on top of that graffiti—there’s more of a back and forth, that dialogue between the artwork and the structure and the natural setting and the viewer and the traffic,” Gonzo muses. Education is key to GASAM’s mission: several different kinds of art classes are also in the works, in hopes that patrons will be able to better identify the skill that goes into street art when they see it in its natural habitat.

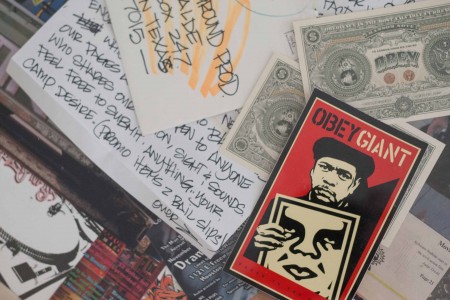

Shepard Fairey is featured both on the gallery walls and in its ephemera cases. Photo by Jessica Almanza.

And then we get into talking about cave drawings, and it’s easy to start to see that the GASAM will be the hippest natural history museum to date. In addition to mural tours and classes, the GASAM is also a vehicle for preserving the history and evolution of the graffiti scene in Houston and beyond. Gonzo envisions future researchers, working on “something as specific as the influence of graffiti and street art on the Mexican American culture in the south,” and not being able to find the right information anywhere else. “In the end, this isn’t really for today,” he explains. “I’m looking at 30 years from now. Today, this history means nothing because it’s so new and current.”

Of course, it doesn’t mean nothing now either—that was clear from the open house, where attendees pored over a visual history of Houston’s graffiti scene in addition to vibrant work by internationally-renowned artists El Pez, Cope2, and Futura. But, why Houston, besides the fact that it’s his hometown? “Graffiti originated in Philadelphia, but it really took off on the subway cars in New York, and it was alive—carrying messages left and right, up and down, across the city,” he says. With its spread-out geography and lingering conservative traditions, it’s no wonder it took Houston about 15 years to catch up. This is a result the efforts of artists like Gonzo, in addition to the natural turnover of city officials and street art’s loosening label of “vandalism” and “gang violence.” But Gonzo reports supportive feedback from all over, recalling a specific message from the website Brooklyn Street Art: “When I saw their email come in, I immediately thought it would be backlash along the lines of, ‘who do you think you are?’ But on the contrary, they loved the idea, and offered to help in any way possible.”

As we talk, it’s impossible to miss his necklace, which consists of about 20 strung-up nozzles from spray paint cans. He’s been wearing it for years, and recently started making more, not so much as fashion pieces but as a diary of projects past. “It grounds me—so no matter what great opportunity comes my way in life, I remember that I used to just be a kid with a can of paint and an idea of being an artist, so my head doesn’t get too big.” It’s history, diversity and creativity—not ego—that are enormous in this space, even as the GASAM is poised to move Houston’s art scene to a new level. Until the formal opening, we’ll just have to enjoy Houston’s masterful street art in its natural habitat.

–Joelle Jameson is a writer living in Houston, Texas.