Kevin Moore, an Independent curator and writer based in New York, has been the Artistic Director and Curator for FotoFocus since 2013. He earned his PhD in Art History at Princeton and has worked as a curator at Harvard’s Fogg Art Museum. He has written books about Lartigue and color photography in America (in conjunction with the “Starburst” exhibition at the Cincinnati Art Museum, which he curated in 2010). He has published articles and chapters on a wide range of photographic subjects, including Elena Dorfman, Bauhaus photography, Minor White, and Robert Mapplethorpe. He is the curator or co-curator for eight shows for FotoFocus 2016.

We conducted this interview, which has been lightly edited for continuity and space, via email in July and August of 2016. The jumping off place for our discussions was the description of the organizing theme for FotoFocus 2016, which Moore has called “Photography, the Undocument” which can be found at the FotoFocus website:

Photography, the Undocument

The FotoFocus Biennial 2016 Theme

Photography is identified with objectivity, documentation, and realism. Yet the medium essentially abstracts the visible world, reducing its surfaces to two dimensions, editing down to a narrowly chosen single frame, and often presenting the world in black and white. Digital technologies of recent decades, allowing for seamless manipulation of photographs, have further eroded photography’s documentary authority. Surrealism historically played on these contradictions, conjuring from within the photographic image the eerie, the uncanny, and the outright bizarre. “Beauty will be convulsive,” wrote André Breton in 1928, referring to art’s ability to break the surface of realism, of the everyday, to reveal sudden insights, even truths. The Undocument is an exploration of alternate understandings of the documentary photograph—its claims to objective realism and simultaneous potential for pure fantasy.

Aeqai: I want to ask you some questions about the overall focus on the Undocument. I’ve read the material that’s available online, but there’s lots more I’d like to know. How did this come to interest you as a focal point?

Kevin Moore: The purpose of a theme is to create unity between lots of different exhibitions (both my own and those of the participating venues). But in setting a theme I’m aware that it has to be something fundamental to photography that’s also broad and all-encompassing. The Undocument is about something fundamental to photography: its documentary character. But you can–and should–question that in all kinds of ways.

Aeqai: Can the same work be read as a document or an un-document, depending on the critical framework?

KM: Absolutely. Even the most earnest and straightforward documentary project has a point of view, a position to further. And photography by its nature abstracts the world. It’s not a natural vision, especially in black-and-white. It flattens and frames the world, which is not how we actually see. So every picture is an artifice, not just the ones that are obviously manipulated.

Aeqai: All photographs have a point of view, and photographs are intrinsically artificial: these are two very important ways that photography does not merely record the world. Are these two factors—the subjective and the artificial—fundamentally connected?

KM: These are two different things, I believe. Point of view is something photographers and their advocates have long used as an argument for convincing people that photography has artistic properties, that it’s not just a mechanical process but is operated by a subjectivity, by someone with something to say.

The second point, about photo being intrinsically artificial, is something people need to be reminded of. Our naturalistic vision is something quite different from the 2-d representation of a photograph. Perhaps the best way to grasp the point is to think about a photograph as a selected tiny chunk of the visible world, flattened, color-distorted, or in black and white, which is completely contrary to naturalistic vision. I also think of photographs increasingly as tiny stage sets, where people perform or put something on view. Theater is artifice; so often is photography.

Aeqai: “Tiny stage sets.” Of course, there are the photographers for whom that is literally true, like Casebere among others. The relationship between contemporary photography and theatricality is a real and interesting thing. I’d like to know more about your interest in that—and, of course, the “tiny.”

KM: That stage-set artifice has been a part of photo from the beginning, but when I think of “tiny,” I am referring to small screens: cell phones, iPads, the places where everyone consumes photo these days. Everyone is looking at their phones as tiny portals to other people’s lives and framing their own lives for transmission.

Aeqai: I was interested in the Breton quote in the online paragraphs, linking photography to Surrealism and the unconscious. But can’t the unconscious and the uncanny also be at work in photography that might be conventionally read as documentary?

KM: Yes, that’s certainly there too. Breton and Surrealism weren’t so much about “strangeness,” as we tend to use the word “surreal” today. It’s more about the ordinary and the potential for the uncanny to erupt from within. It’s the shiver you might feel at some random moment of the day, not knowing precisely what it is you’ve just encountered. That aspect of photo is what makes it possible to see the familiar in unfamiliar ways. If offers a step back from what we often see and think we know.

Aeqai: My sense of the uncanny is that, at its core, it is the transformation of the familiar into the unfamiliar—hence Freud’s original term “unheimlich.” Is that what you see as being at the core of Surrealism as well? To me, this transformation of the familiar into the unfamiliar is one reason that it seems that the documentary impulse is perfectly likely to stray into the uncanny.

KM: Yes, that’s a definition of uncanny. It is something very close to the canny. And that is at the heart of true Surrealism. We tend to use the term “surreal” today to say something is weird when, in fact, truly surrealist things are uncanny things–close to looking normal with a frisson of the bizarre. Most often, and at its most effective, it is a transformation that happens before your eyes and is unexpected.

Aeqai: It seems to me that there are strong elements of the uncanny even in some of photography’s earliest, most apparently documentary artists, such as Atget, among others. Is there something intrinsically uncanny about the photographic process? The photographic frame of mind?

KM: Theoreticians of photography, such as Rosalind Krauss and Hal Foster, have written about the relationship between photography and Surrealism. It’s a match made in heaven: a modern technology that alienates from reality as much as it claims to capture it; a movement that seeks to crack open the surface of reality and examine the subconscious, the “true reality.”

Atget, of course, was just documenting (yet still, with a certain subjectivity) and wasn’t thinking about Surrealist or Freudian precepts, so far as I know. But who is to stop anyone later on from seeing these qualities in his images and co-opting them for discussion? Photography is wonderfully (or tragically, depending on how you feel about it) adaptable to new contexts and platforms of meaning.

Aeqai: What makes adaptability tragic?

KM: “Tragically” in the sense that as a medium, photo is highly promiscuous and disloyal to any prescribed art code. It can stray in any direction, even into the gutters of advertising and pornography, and does not play by any established rules, or at least the rules the Modernists set for it (Szarkowski, chief among them). Photography can be a handful for theorists trying to make classifications between art and non-art, or to set standards.

Aeqai: I wonder about the source of what you call the “promiscuity” of the medium itself: is it in the judgment of the culture or the practitioner of the form or the audience? Is that promiscuity inherent in all photographs?

KM: In terms of “promiscuity,” I mean simply that photo–as data, as bytes–is so easily distributed, appropriated, altered. Authorship is increasingly difficult to control. Which raises the point that if a photo-document is presented as some sort of evidence, which it still commonly is, how do we know if the photo is unaltered or who took it or if it was actually staged or to what degree it was staged? There’s an interesting show at the Bronx Documentary Center that shows “documents” of 20th century incidents involving photo as evidence, reminding us that citizens armed with cell phones are now involved in the political process in unprecedented ways.

Aeqai: You brought up Szarkowski before. I take him to be an interesting figure. I imagine that as curator at MOMA he may have helped define, perhaps rigidly, the canon of high modernism (and the beginnings of the post-modern). But the message that I got from Looking at Photographs was very liberating (for me, at that period of my life). Szarkowski seemed to celebrating, in part, photography’s radical indeterminacy. It was clear in a photograph that “we” were seeing things, but a lot harder to know just who we were at that moment: a judge or a pervert or an assassin.

KM: Szarkowski set some rigid high modernist standards but he was also incredibly catholic in his approach to photography, including anonymous amateur snapshots, commercial photo, and all kinds of imagery traditionally not considered art in his canonizing publications. He recognized this unruly aspect of photo. At the same time he lived during a period when setting modernist standards (following in the theoretical wake of painting and architecture) seemed like the thing to do.

Aeqai: I’m curious about the sorts of critical frameworks—the kinds of historical and theoretical writing—that you see as essential to your thinking about the Undocument.

KM: I’d like to point out that I may have come up with this word Undocument but it’s not a very original idea. It is something that is fundamental to photography and has been discussed in different terms from the beginning. I’m not really interested in rolling out a theoretical history of the idea here, but am simply offering it up to a general audience in order to give them something essential to think about in terms of looking at and appreciating photography.

I also want to emphasize the relation between photo and our overall views of realism and reality. It’s important to recognize this fundamentally troubled aspect of our lives in a science-based, post-Enlightenment era: we imagine as much as we encounter. I see this aspect of photography and think it’s one of the most compelling things about the medium in this era of cyber-everything. We still look to photo for a grounding in reality, yet we see more and more that it is compromised. And maybe we’re realizing we prefer it that way, untethered from reality.

Aeqai: We began by exchanging views about what constitutes the Undocument. I was wondering what you thought constituted a photographic document? And perhaps a little more broadly, what you think of as the purpose of documentary photography?

KM: I think a photographic document is a fantasy of “truth,” “reality,” “objectivity.” We of course value these concepts and strive to unearth them in all walks of our lives, but these are values that essentially evade us and photography plays a large part in our “quest to reach the horizon.”

Aeqai: Whose fantasy? The photographer’s? The audience’s? The culture’s-at-large?

KM: That’s a culture-wide fantasy.

Aeqai: This discussion of the documentary as a fantasy of truth, reality, and objectivity seems very timely in light of the history of the debate over photography’s status as documentation. It seems to me that your Weston show “After Industry” gives you the chance to think about the changing nature of the document. Can you say something about the kinds of choices you made for that show?

Frank Gohlke, “Grain Elevators”, Cyclone, Minneapolis, 1974

Collection of Gregory and Aline Gooding. © Frank Gohlke. Used

with permission. Courtesy of Gallery Luisotti, Santa Monica

KM: The Weston show selection is first and foremost credited to the collector, Greg Gooding, who went out and collected this particular group of pictures. As Curator, I made a certain cut. But what I think you see in it is a narrative of different views of nature during the 20th century–starting with some awe perhaps for the symbolic and formal beauty of industry (Brandt, Renger-Patzsch) and then some disgust or absurd humor in response to the effects of industry on the environment (Baltz, Gohlke), and eventually, perhaps, some satisfaction in seeing nature reclaiming abandoned landscapes (Ruwedel). In terms of a history of documentation, you might say that there are different periods of belief in the power of documentary photography to actually change the world. Think of Lange and Hine. But then you also see photography as a witness without much power to change the world (Frank) and photography as a selfish interest in showing the world in order to represent a photographer’s inner state or psychology (Arbus, Winogrand perhaps).

Aeqai: You bring up Arbus and Winogrand to distinguish their work from the documentary photographers who believed they might “actually change the world.” But wouldn’t this place their work squarely into the category of Undocument—work that resists the direction of “cyber-everything” and appeals openly to our emotions?

KM: I think we are missing something essential here about the Undocument: it is both document and not document, not either-or. A photograph will propose some sort of truth but may also reveal, to some large or small extent, a polemic of a given photographer. Let’s explore some examples from the “After Industry” exhibition.

Albert Renger-Patzsch aligned himself with the idea of the document by embracing photographic objectivity to “prove” that factories and nature were both beautiful and could co-exist in perfect harmony–a fantasy, but it looked true in his book Die Welt ist schön.

Walker Evans employed a documentary style–a cool, detached, rigorously frontal “styleless style”–to photograph sharecroppers in the South. But his book with James Agee, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men, was celebrated in its time for being a new kind of “immersive journalism” in which the authors presented the dignity of their subjects through the style of their presentation. In other words, the work wasn’t as objective or “documentary” as it seemed to be on the surface.

New Topographics photographers of the 1970s, such as Lewis Baltz and Robert Adams, also deployed Evans’s sense of detachment but showed some ambivalence about the American built environment, which was more a meditation on the state of the US, its culture (or lack thereof) in general.

Mark Ruwedel, “Dusk #21 (Antelope Valley #230)”, 2008, Collection of Gregory and Aline Gooding. © Mark Ruwedel. Used with permission. Courtesy of Gallery Luisotti, Santa Monica

Mark Ruwedel’s series of reforested railway grades are some of the most formulaic images in the show, always taken from the same angle, yet also some of the most romantic. His use of the document-idea is to confront the return of nature and to invoke a very romantic idea of ruins and man’s eventual perishing from the world. It’s a document of something but it also sets off a metaphorical flight of fancy.

Aeqai: What about pictures of people? Do you think that audiences look to portraiture for a different sense of “reality” than they look to other genres? How might the Zanele Muholi photographs help sort through some of that?

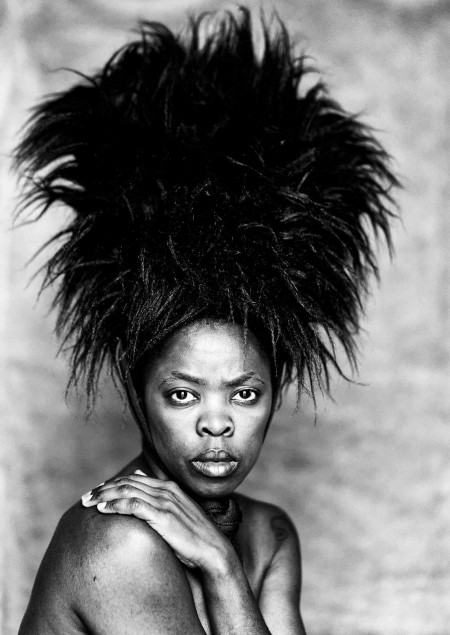

Zanele Muholi, “Bester II, Paris”, 2014. © Zanele Muholi. Courtesy of the artist and Yancey Richardson Gallery

KM: Zanele’s portraits are a great example of how the document seems to promise something definitive yet, the more you look at the work, conclusions dissolve. In Faces and Phases, her portraits of lesbians and trans-gender folks, you see them at a particular moment of their self-presentation, when they are projecting a certain identity through clothes, hair, attitude. But there are follow-up portraits that show the same sitters looking very different, showing their identity as shifted, emphasizing that it’s all really fluid, there is no one reality, and no stable identity. Even more compelling in relation to this idea are Zanele’s self-portraits, not just because she adopts different personae, stereotypes, Western fantasies, but also in the way she manipulates the skin tones through basic photographic tools. Skin bleaching is a huge part of African’s culture and might be seen as commercializing a form of self-loathing. Zanele is playing with this idea through photography and also searching for a stable sense of self through all the myriad projections. They are all ostensibly documentary photographs, very straight and not noticeably manipulated, but all very queer when you get right down to it. So the document gets undocumented.

Aeqai: Do you think that that the distinction between document and undocument crosses cultural boundaries? Do fantasies about truth, reality, and objectivity work the same ways on both sides of the colonial/postcolonial boundaries?

KM: I think it all works similarly enough, or as well as it can. Specific codes will read differently to different groups in different places and different times, but there exists an impulse to share a common ground. Photography is still our visual Esperanto, although, naturally, lots of misunderstandings are bound to occur, and that is where the fun begins for the critic, the art historian, or the curious visitor.

Aeqai: How is the focus on the Undocument related to some of the other work you’re most likely to be known for in Cincinnati, such as the “Starburst” show, for example, or last FotoFocus’s wonderful Vivian Maier exhibit?

KM: I don’t know that I’m particularly consistent in the subjects I explore, unless it’s to try to relate history to the present day. That’s the burning question for me as an art historian: how is the past relevant to the present? I think every project you choose to work on needs to present a clear answer to that question at the outset. Otherwise, it’s just some random show without much interest. The Undocument, though, is an important theme because it’s basic and essential to photography and, more importantly, basic and essential to the way we gauge our own understanding of realism and reality. For me, this transference from photography to life questions, questions of politics and existence, is the most compelling reason to care about photography.

Aeqai: What do you suggest that people see first among your shows for FotoFocus?

KM: If someone wants a comprehensive experience, I would suggest doing the Walnut St corridor: CAC, 21c, Weston, and Freedom Center. That’s all 8 of my curated shows. The Freedom Center shows, I think, will be especially popular to a wide audience. They don’t usually host art exhibitions; the political nature of those artists’ work (Zanele Muholi, Jackie Nickerson, Robin Rhode) will have extra resonance in the political climate of the moment.

Some of the Participating Venue shows also stand out: “Kentucky Renaissance” at the Art Museum and “Evidence” at the Art Academy of Cincinnati, plus Wave Pool’s show, “The Peeled Eye.” Wave Pool is also taking over the FotoFocus Art Hub this year with a related installation, located on the lawn of the Freedom Center. The total event is overwhelming and intended as a buffet–you choose what attracts your interest.

Aeqai: Are there some works or details or issues that you’d especially like your audience to keep an eye open for?

KM: Roe Ethridge’s show is particularly important in the larger art world. His work has seemed opaque, “conceptual” to many people, but read the wall text and the catalogue essay and take it from there. There is much delight in his photography if you stop worrying about what exactly it all means. They are personal narratives embedded in what looks like advertising photography. Also the racial and political content of Zanele’s show in particular is timely and she handles her themes beautifully. What might not be obvious is that the Freedom Center shows by 3 artists are a balanced racial hand: Zanele is a black woman from South Africa; Robin Rhode is a mixed-race South African man; Jackie Nickerson is a white European woman who photographs in southern Africa. Not to make too much of that, but I think it’s important to think about race in complex and integrated ways.

Aeqai: What were a couple of the most interesting things you learned—about photography, photographers, or even yourself—in the process of curating the shows for this year’s shows?

KM: Roe’s show was very challenging. He’s an expansive thinker. We spent a lot of time together puzzling out the meanings he’s searching for in his work. He and I both learned a lot from each other, I believe. I also learned a lot about Africa and have thought a lot about race and sexuality there in relation to our own tense climate.

Aeqai: Can you say a few words about any upcoming curatorial or scholarly efforts you’re working on in the weeks and months after FotoFocus?

KM: In addition to the Roe Ethridge catalogue called Neighbors, I have two publications out next month: I am a contributor to the new MoMA catalogue, Photography at MoMA: 1920-1960, and I wrote the intro to a book of photographs by a longtime Vogue photographer and illustrator, Eric Boman: A Wandering Eye. I’m also working on a book with Larry Fink of a series of photographs he took of Andy Warhol and the Factory in the 1960s. And I’ll begin work on FotoFocus 2018 exhibitions, which I cannot yet talk about.

Aeqai: Thanks again for everything.