Two of the three FotoFocus 2016 exhibitions offered at the Art Academy of Cincinnati were curated by former AAC photography instructor, Will Knipscher. These included the historical body of work Evidence, created by Mike Mandel and Larry Sultan in the 1970s, plus two bodies of new work by Mandel with his new collaborator, wife Chantal Zakari, and a solo exhibition in the ground floor by Peter Happel Christian, Sword of the Sun. Additionally, Knipscher had a small solo exhibition of his own photo-based work at the Carnegie in Covington, Kentucky, just across the Ohio River.

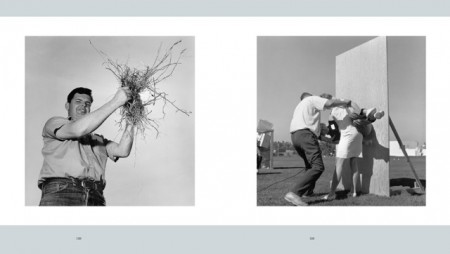

Evidence is an exhibition of photographs from the original 1977 publication by Mike Mandel and Larry Sultan. It is comprised of 59 anonymous photographs culled over three years from the archives of various governmental and public and private corporate entities and agencies (including Bechtel Corporation, the Beverly Hills Police Department, the Jet Propulsion Laboratories, NASA, the U.S. Department of the Interior, Stanford Research Institute and a hundred other corporations, American government agencies, and educational, medical and technical institutions), decontextualized then recontextualized through juxtaposition and sequencing. The photographs all were made of records of tests and experimental pursuits or sometimes evidence of crimes, now divorced from their intended documentary meanings (perhaps thereby qualifying for Kevin Moore’s 2016 FotoFocus theme of “The Undocument”). They are photographic evidence, but just of what is now untethered and entirely up in the air. The critic Kenneth Baker of The San Francisco Chronicle wrote at the time that the project demonstrates brilliantly the degree to which “we have no calculus to unravel relations between what a picture shows and what it explains.” The book is considered a seminal marker in the conceptual movement of the medium away from celebrations of authorship or narrative. Which is not to say no narrative exists, because Mandel and Sultan have carefully sequenced the work to produce a sort of rhythm, in pursuit of what they called at the time “a poetic exploration upon the restructuring of imagery.” Unfortunately some of that is difficult to trace in exhibiting the images singly rather than as couplets (double page spreads in the book), but the enigmatic quality of the individual images remain. There is an erie sense of ‘70s dread in the pictures of unidentified experiments, perhaps classified (censored) in their time, undercut by an odd amateurish quality in the photographing. You can feel the course change to the medium of photography and perhaps even art generally caused by the powerful nudge of the tugboat of Evidence.

Evidence did not materialize from thin air; Mandel and Sultan produced other collaborations earlier the ‘70s and well into the ‘80s, including large dada-esque billboards and publications like The Seven Never Published Portraits of Edward Weston (various people named Edward Weston from around the country, responding to Mandel’s queries) and How to Read Music in One Evening (both Clatworthy Colorviews, 1974), sequencing found advertising illustrations. Mandel was already producing interesting photographic work before meeting Sultan (both were SoCal guys who met as students at the San Francisco Art Institute in the early ‘70s and gravitated to each other in the post-hippie culture of the Bay area), including People in Cars (random records of people in their cars) and Myself (timed self-portraits in which Mandel would insert himself into unsuspecting groups of strangers), then after their meeting, the famous Baseball Photographer Trading Cards (1975), photographs of noted photographers posed as ballplayers, replete with photography related stats on the reverse.

[Full disclosure: I knew both when students at SFAI. I’d already met Mandel when we had a three artist exhibition (with Les Krims) at Ohio Silver Gallery in Los Angeles, and was in the original set of Baseball Photographer Trading Cards (ripping off my catcher’s mask to go after a high pop-up) but didn’t make the published cut after Mike went East and added the photographers, curators, critics out there.]

Subsequently Sultan became internationally known for his SoCal based, “documentary” photography projects (Pictures from Home, The Valley, Homeland) and died in 2009 at the age of 63. Mandel moved East to Massachusetts from where he has been making large public arts installations – photo-based mosaic murals of porcelain and glass tile – installed around the country since the 1990s. He teaches at Tufts University and The School of the Museum Fine Arts, Boston, as does his wife and current collaborator Chantal Zakari. They live in Watertown, a quiet Boston suburb.

The ACC exhibit includes two small bodies of recent work Mandel has done with Zakari, Lockdown Archive and Shelter in Plates, both made in response to the events following the terrorist bombings of the Boston Marathon in 2013. The bombers were identified as Chechen brothers, one of whose life ended after an an exchange of gunfire with police in the street of Watertown, before his younger brother subsequently ran him over with a stolen SUV in his escape. An unprecedented manhunt for the younger brother ensued, with thousands of law enforcement officers searching a 20-block area of Watertown, during which authorities told residents of Watertown and surrounding areas, including Boston, to stay indoors and “Shelter-in-Place”. The public transportation system and most businesses and public institutions were shut down, creating a deserted urban environment of historic size and duration. In the evening, the younger brother was discovered hiding in a boat in a Watertown resident’s back yard. Located within the boat by thermal imaging, he was shot (in the boat), and arrested.

Mandel and Zakari responded to this extraordinary situation by mining the web for photographs fellow Watertown residents made through their curtains and windows of the police sweeps of their neighborhood, to create the reverberantly claustrophobic Lockdown Archive, and then, using a number of these images, they created Shelter in Plates, a set commemorative porcelain plates suitable for presenting on a wall or display shelf. Additionally they made a limited edition poster, stacked in the gallery, offered free to exhibition visitors.

Mike Mandel and Chantal Zakari, Shelter in Plates, 2014. Stoneware Plates, 10½ inches. Courtesy of the artists

On the ground floor gallery, Knipscher has curated an exhibition by St. Cloud, Minnesota based artist Peter Happel Christian, titled Sword of the Sun. The short press release, drawn nearly verbatim from the artist’s statement, says Happel Christian’s works are “made at the intersection of photography, sculpture, and performance”, that he “examines photography as a fluid method of description or invention, and situates his work as a comprehensive studio of the natural landscape, a complicated place of human experience and contemplation.” What this means in execution is a collection of two and three dimensional pieces, on the walls and on tables, representing a photographic response but often absent a camera, “reaching into the world physically to interact with my subject matter.” So a photo-semblance image may only be drops of developer allowed to run down photographic paper, creating sculptural cone-like shapes. Or a pencil with partly chewed gum stuck on its end may sit on a display table as the “magic wand” it represents for his young child. The accumulated effect of images and objects is what Happel Christian considers a resonant “synchronized mutation between a descriptive reality and a constructed reality.”

Drag and Drip II, 2013, unique gelatin silver print, 14 x 11 inches, from Peter Happel Christian: Sword of the Sun

Happel Christian’s accompanying self-published book, Sword of the Sun, accompanies the exhibition, a special feature of which are unprocessed sheets of resin-coated darkroom paper serving as end papers to the book which slowly record unstable, ghost images of the front and back covers.

The AAC exhibitions closed November 4, but an exhibition of curator Knipsher’s own photo and photosensitive materials-based art work is installed at The Carnegie through November 26.

–William Messer