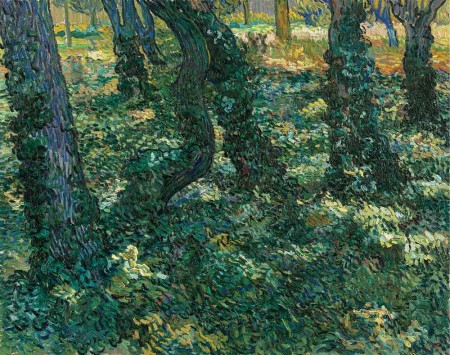

Okay, I’ll go first. In my decades of getting to know and love the Cincinnati Art Museum’s permanent collection, I had never really liked Van Gogh’s “Into the Undergrowth,” painted a month or so before he died in 1890 at the end of a whirlwind career that lasted no longer than ten years. “Into the Undergrowth” came to Cincinnati around 1944 when it was bought by Mary Johnston and entered the Museum’s collection in 1967. It had always seemed to me that it was painted in more than Van Gogh’s usual haste. There is a claustrophobic quality to it: the distant background seems virtually walled off. And then there are the two figures, ominous stick figures sketched in, but barely human.

Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890),Undergrowth with Two Figures, June 1890, oil on canvas, 19 ½ x 39 ¼ in.

(49.5 x 99.7 cm), Cincinnati Art Museum; Bequest of Mary E. Johnston, 1967.1430

One measure of the triumph of this gem of a show is how much more I like this picture now.

The exhibition chooses to contextualize the Van Gogh by looking in a thoughtful and extended way at the genre of the “sous-bois”: paintings of the forest floor. These are not the same as the insect and lizard-laden pictures of shaded clearings done in the 17th century (and shown to great advantage in the Museum’s “Northern Baroque Splendor” show last year), though there must be some connections. “Sous-bois” paintings get up close to the trunks of trees and the spaces that immediately surround them. They are not vistas. The paintings are dense with life (flora, and never fauna, at least in this show), but generally limited to the sorts of life that thrive in the shade of the trees that define their space. But not only shade: it seems to be part of the genre to capture the sunlight that makes its way through the leaves and dapple the forest floor.

At the risk of revealing how much of a formalist I can be, I also feel that sous-bois paintings raise important issues about how to draw with paint. What sorts of marks can best capture and abbreviate the virtually infinite number of leaves and twigs and spots of light that constitute the floor of a forest? It is fair to say that this need to adjudicate between the claims of representation and the claims of abstraction becomes a landmark issue as the nineteenth century moves towards modernity. The sous-bois pictures also raise other formal problems, including how to make compositional sense of the strong verticals that stretch up out of the softer, horizontal landscape, breaking up pictorial space on the canvas into distinct sections.

To get us ready to make sense of the Van Goghs—the exhibit has an astonishing eight of his works on loan—the curators have gathered some fifteen or so French paintings from the 1840s through the 1890s, and they are an all-star list: Monet, Renoir, Cezanne, Seurat, Gauguin (mostly borrowed from abroad), as well as a number of pictures by members of the Barbizon school (including seldom-seen works from the CAM’s own collection). They are not, by and large, depictions of the forest primeval; they are woods with paths and sometimes even intersecting paths. A number of them feature people at work or at rest, whose presence reminds us both of the place of nature in the human economy and of the scale of the trees, which are sometimes commensurate with human height and which sometimes soar far above them.

Claude Monet (1840–1926),Forêt de Fontainebleau, 1863–65, oil

on canvas, 19 11/16 x 25 9/16 in. (50 x 65 cm), Kunstmuseum

Winterthur; Donated by the Galerievereins, 1934, 632

Monet’s “Foret de Fontainbleau” (1863-65), done in his twenties, allows us to see the precocious artist thinking about light and paint. To paint the scene, he has a color problem to work out: how to represent both the warm light dappling the ground and the spots of cool blue light visible through the breaks of leaves. What sort of drawing, what sort of painting, is right for these two types of spots of light? To say that Monet resolved this by making those spots into small blobs of paint is to say something self-evident, perhaps, but it will turn out to be the same quality that will make the move towards painterly abstraction seem self-evident by the turn of the century. Narcisse Virgile Diaz de la Pena’s “Forest of Fontainebleau” (1868) takes us to a different, considerably more unruly, place in the woods. Some sun cuts through to bathe the half dozen or so trunks of trees that block our way, but the forest is so thick here that we can barely make out any sky. With no rational or obvious sources of light, the brightly illuminated trunks seem to define a more magical space than Monet’s, though at the same time, it is a more sinister clearing. Not all magic, after all, is benevolent.

Narcisse Virgile Diaz de la Peña (1807–1876),Forest of Fontainebleau, 1868, oil on canvas, 33 ¼ x 43 ¾ in. (84.5 x 111.1 cm), Dallas Museum of Art; Munger Fund, 1991.14.M

We can see how Van Gogh handles the dappled light in one of the exhibit’s masterpieces, “Undergrowth” (1889). The actual undergrowth here is all ivy, more undulating than Monet’s flat ground but less tumultuous than the rocks and ridges of Diaz de la Pena’s. It catches light the way the top of the water would in a gently troubled sea. This painting is also particularly interesting for the way that Van Gogh has found to make each brush stroke represent a thing—an ivy leaf, for example. The forest floor is a dazzling array of ivy, pointed up in slightly but infinitely varied ways, each leaf precisely one brush stroke in size. Van Gogh seems to have been drawn to trees in a line, often in intersecting alleys, and so it is here: a diagonal row of five trees dominates the foreground. Most of them are relatively straight and vertical, but in the center, two twisted trunks seem to lean on each other, intertwine, and possibly merge. This is part of the motif of a clinging pair that we encounter often in Van Gogh’s work—typically a couple walking in a park—who give each other strength and pleasure from which it seems fair to say that the painter feels excluded. Are these couples stand-ins for Van Gogh and Gauguin? Their shape also suggests an interesting spatial issue; we can see through the trees to a section of dappled ivy hidden behind them, revealed by an opening like a gothic arch. (Monet found this sort of shape of pervasive interest in his 1880s paintings of the rocks at Etretat.)

Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890),Undergrowth, July 1889, oil on canvas, 28 ¾ x 36 5/16 in. (73 x 92.3 cm), Van Gogh Museum,

Amsterdam (Vincent van Gogh Foundation), s51V/1962

Around the same time, Seurat was also thinking about what a single brush load of paint could represent. In “The Forest at Pontaubert” (1881), executed some five years before he began to paint in the style that became known as Pointillism, we can see him building up his canvas out of marks that are getting smaller and smaller, though they haven’t yet become dots. The composition suggests the enormous influence of Japanese prints, which allowed negative space to carry fully as much weight as positive space, and opened the way for completely remarkable experiments in design in European art. There are three trees in the foreground, all crowded to the right of the canvas; the left foreground is empty, and most of the background is a blur with a handful of slender verticals punctuating the wall of green shade. It is a radical painting in its own way, depicting the loss of form and definition, like some sensuously dangerous trap in a medieval quest romance through the woods.

Georges Seurat (1859–1891),The Forest at Pontaubert, 1881, oil on canvas,31 1/8 x 24 5/8 in. (9.1 x 62.5 cm), The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New

York; Purchase, Gift of Raymonde Paul, in memory of her brother, C.

Michael Paul, by exchange, 1985, 1985.237

Dematerialization also seems to be the agenda in Renoir’s “In the Woods” (1880), one of the most remarkable and surprising paintings in the exhibit. It is, at the core, a formally elegant painting in which a path, depicted in vanishing point perspective, extends in a straight line through the woods in the foreground and the woods in the background, with a brushy clearing in between. It seems like a stunningly bright day in the height of spring. For an artist who seems not to have been able to work his way out of the trap of depicting soft but tangible flesh, in this landscape, weight and mass seem to have evaporated. Each of the painter’s marks seems to want to dissociate itself from the others. The ground is composed of thousands of mottled marks, making it feel as if one is about to walk on air. Who can tell the dapple from the leaf?

Pierre-Auguste Renoir (1841–1919), In the Woods, circa 1880, oil on canvas, 21 15/16 x 18 ¼ in. (55.8 x 46.3 cm), The National Museum ofWestern Art, Tokyo; Matsukata Collection, P.1959-183

This matter of the architecture on the surface of the canvas, the thousands of painters’ decisions that produce the brushstrokes of which a picture is constituted, comes to be more and more important as the 1880s progress. The CAM has brought in a remarkable Cezanne, “Interior of a Forest” (c. 1885) in part to let us see what a deliberate and methodical rethinking of brushstrokes can do to painting. Like interlocking tiles, they hold form and space together. They do not represent the objects they depict; each one is a pretty radical abbreviation of matter and space. The whole painting is like a grid, built out of row upon row of brushstrokes, but one designed to bring out shape, gravity, and movement. In the picture, we seem to be standing on a path that proceeds a very short distance ahead of our point of view and then ends abruptly, either because it is swallowed up by the undergrowth or because Cezanne lost interest in portraying the continuity of space. In the dead center of the painting is a bright, tilted clearing, dazzling green and even white in the dappled light. The foreground is a complex interweaving of the thin lines of young trees that tend to simply disappear towards the top of the frame. Three on the right start off as parallel lines, like the strings of some musical instrument only the forest can play. A few on the left cross over and meet at the top, creating something like a gothic arch. In the openings between the various spindly trunks, it is as if we can see into different spaces, even different worlds. As a brilliant friend of mine said when seeing this picture, “It’s like there are five paintings here.”

If everything about Cezanne’s brushwork seems measured and patient, nothing in Van Gogh’s brushwork seems measured. That same friend pointed out how startling it was to see the impatient way Van Gogh attacked his canvas, always in a rush to lay things down. The Museum was able to secure the loan of “Tree Trunks with Ivy” (1889), which is likely to have been a study for the more finished “Undergrowth,” only from a slightly different angle. From where Van Gogh set up his easel for this work, he was interested in a more classicizing composition, those same five trees now in a straight line in the middle of the canvas. There is a second row of trees directly behind them. From this point of view, the two crooked trees are still paired off but do not intertwine. Light hits a tree on the right and seems to be bursting out of the trunk and flowing across the ivy like a waterfall. In this smaller version, we feel all the almost painful urgency with which Van Gogh painted. If you look closely at the surface (never a bad idea), it looks like some of the painter’s marks have been squeezed out of a tube directly onto the canvas. The colors seem schematic, placeholders to remind Van Gogh of appearances or perhaps of feelings. (How else can we explain the handful of red strokes at the base of one of the trees?) Sometimes it seems as if one of the things one can say about Van Gogh is that he is a painter who struggled, often successfully, to find ways to make his impulses and compulsions work for him. At least in his paintings.

Vincent van Gogh (1853–1890),Tree Trunks in the Grass, late April 1890, oil on canvas, 28 9/16 x 36 in. (72.5 x 91.5 cm), Collection Kröller-Müller Museum, Otterlo, KM 100.189

In “Tree Trunks in the Grass” (1890), tall flowers are taking the place of dappled shade, bringing the spots of light towards the foreground and literally lifting the light up off the ground. In the background is an inviting path, offering us an alternative way in and out of this world. The painting is dominated by a tree trunk that takes up the left foreground. It is made up of bold and jagged lines that zig-zag up and down. It is not self-evident what either the shapes or the colors of which they are constituted stand for, or whether they could possibly be found in nature. They belong to a system that seems to have been invented specifically for this picture. The tree splits just above the ground to become a pair of trunks, united only as the roots enter the ground. There is only one curve in the whole tree, a gracious dip that links the two diverging trees.

It only remains, really, to contextualize the purpose of the human figures in the sous-bois tradition. For Millet (Bodmer and Millet, “In the Forest,” [1852]), there was no question about them: the purpose of the forest was to frame and dramatize the arduous nobility of the people who worked in it. Millet’s forest is enchanted, and not necessarily in a good way; these are the woods in which Hansel and Gretel could get lost. Millet’s rural workers were most in their element in the open fields. Corot’s “Large Oak with Three Peasants” (c. 1860-65) seems driven by a similar idea, though no rural workers ever had to carry as heavy a load as Millet’s regularly did. Pissarro’s print, “Wooded Landscape at the Hermitage, Pontoise” (1879) has a single figure in it whose presence is more equivocal. Though the print itself is a bravura combination of soft ground, aquatint, dry point, and scraping, the figure seems a cautious addition, neither laboring nor dreaming. Perhaps he is a sort of stand-in for the artist: he is looking, more or less, at the same thing we are looking at. In the earliest (and least interesting) of the Van Gogh paintings in the show, “Girl in the Woods” (1882/83), a child stands near the exposed root system of an old and mighty tree. Behind her, a path winds its way through the forest. In a remarkable letter to his brother Theo (cited at some length in the excellent exhibit catalogue), Van Gogh explains that he gave up on the sketch because he was being bothered by the fact that there were “passers-by, and so when I had got the study to the point you see I couldn’t bear it any more.” But he also says that the figure is a maguffin. He put her there “simply and solely for the size” and possibly “to provide an accent.”

What happens if we take all this rich and visually exhilarating contextualizing back to the CAM’s “Into the Undergrowth”? In the panoramic double canvas, the trees are arranged into rows, providing alleyways through the woods. The central figures seem to be standing baffled, unsure where to go next in the formless forest. But it looks as if to either side of them, there are clear pathways out, or at least through. The undergrowth is overgrown, though lushly in bloom. The flowers might be as tall as people’s knees, maybe higher. The line of trees seems to be plowing through them like a boat cutting the waves. There is something both lovely and threatening about it. If you are not careful, the undergrowth could swallow you up. But dappled light or no, there has been a tradition of sous-bois that can be both sinister and beautiful.

The catalogue says of the two figures both that they are perhaps “lovers” and that they are a “ghostlike couple.” I think of them as Mr. and Mrs. Death. There is something hallucinatory about them, but they also seem like another version of the joined couples from which the artist is excluded. It is hard to see them as out for a stroll; they stand frozen in the clutter. There are pathways through these woods, but they seem unable to avail themselves of them. But where would they go? They would have to come towards us, because in the distance behind them, there are no welcoming networks of the paths not taken. There is a dark curtain that fills up the horizon. Storm coming? An impassible wall of blackbirds? In the upper right corner, in a detail I had never noticed before, there are brilliant, near-black lines radiating from behind the tree farthest to the right. They are like explosions of whatever is the opposite of sunlight; they are like Milton’s darkness visible. It is terrible and awesome and grand.

There are some things I was surprised not to see in the show. I kept thinking that Courbet would provide a significant exemplar of the sous-bois, and that his brushwork represented an important chapter in French painting that was omitted. I wondered whether Munch or other examples of Scandinavian symbolists should have been part of the show, both for their way of seeing the mysteries of the forest experience and for their palette, which seems related to Van Gogh’s. But these are small questions on my part. Look: there’s still a month. Go see this show. See it twice. Eight Van Goghs do not wend their way to the New World that often, let alone penetrating to the heart of the Midwest. Frankly, you could see it for the Renoir alone, not to mention the Cezanne. This is an exhibition you will be sorry if you miss.

–Jonathan Kamholtz