Galleria Umberto, 1925, oil on canvas, 44 5/8” x 19 13/16”. Private Collection, Courtesy Neue Galerie, New York, SL9.2016.14.1. © 2016 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

In “Max Beckmann in New York,” the Metropolitan Museum of Art has brought together 14 works painted when the artist lived in the city in 1949 and 1950, and 25 earlier paintings (1920-1948) from New York collections. Although the New York-centric focus would appear to be narrow, the show provides a concise overview of his oeuvre.

Self-Portrait in Blue Jacket, 1950, oil on canvas, 55 1/8” x 36”, Saint Louis Art Museum, Bequest of Morton D. May SL.9.2016.24.1. © 2016 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

The exhibition, organized by Sabine Rewald, The Jacques and Natasha Gelman Curator in the Department of Modern and Contemporary Art at the Met, is built around Beckmann’s Self-Portrait in Blue Jacket, 1950, which was included in the Met’s 1950 “American Painting Today” show. Beckmann was on his way from his apartment at 38 West 69th Street to the Museum to see it when he suffered a fatal heart attack, dying on December 27, 1950. The “poignant circumstances” of the artist’s death inspired the show, according to Rewald.

Family Picture, 1920, oil on canvas, 25 5/8” x 39.3”, The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Gift of Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, 1935. SL.2016.18.2. © 2016 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

In this painting, Beckmann evokes the atmosphere at the salons his first wife’s (Minna) mother-in-law, Ida Tube, hosted in Berlin.

In this painting, Beckmann evokes the atmosphere at the salons his first wife’s (Minna) mother-in-law, Ida Tube, hosted in Berlin.

Going back to the beginning, Beckmann was born on February 12, 1884, in Leipzig. His middle-class family was not in favor of him becoming an artist, but against their wishes, he enrolled in the Weimar Academy in 1900 and went to study in France in 1903.

It was Beckmann’s traumatic experiences as a volunteer medical orderly in WWI that shaped his work as he moved from an academic style to his raw expressionism. During the Weimar period (1919-1933), his career flourished. But his fortunes changed when Hitler came to power. Beckmann was branded a “cultural Bolshevik” and removed from his post at the Art School in Frankfurt. That year, 1937, the government also seized more than 500 of his works from German museums and included some in the infamous “Degenerate Art” exhibition in Munich. The day after Hitler railed against this type of art in a 1937 radio address, Beckmann and his second wife, Quappi (Mathilde), left for Amsterdam. It was intended to be a short stopover on their way to the U.S.; however, it took a decade to reach America. In 1947, the director of the Saint Louis Art Museum, Perry Rathbone, secured a temporary teaching post for Beckmann at Washington University. Two years later he was hired to teach at the Brooklyn Museum Art School, and the Beckmanns moved to Manhattan.

The Bark, 1926, oil on canvas, 70” x 35”. Richard L. Feigen, New York, SL.9.2016.9.1 © 2016 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Recalling their Italian honeymoon, Beckmann painted his second wife, Quappi (Matilde), on the upper keel of the boat.

Self-Portrait with Horn, 1938, oil on canvas, 43 ¼” x 39 ¼”. Neue Galerie New York and Private Collection SL.9.2016.19.1 © 2016 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

Beckmann was fascinated, one might say obsessed, with his own image. He did some 80 self-portraits between the ages of 11 and 66. The last wasSelf-Portrait in Blue Jacket, the fulcrum of the exhibition. In a three-quarter-length pose, his cobalt-blue jacket, battling with his orange shirt and sweater vest, hangs on his gaunt frame. His right hand is in his trouser pocket, and his left elbow rests on the back of a vivid turquoise chair. His eyes are narrowed and slew to the left, and his mouth is hidden as he takes a drag on a cigarette. There’s a nonchalance to the artist’s posture, but a wariness in his eyes.

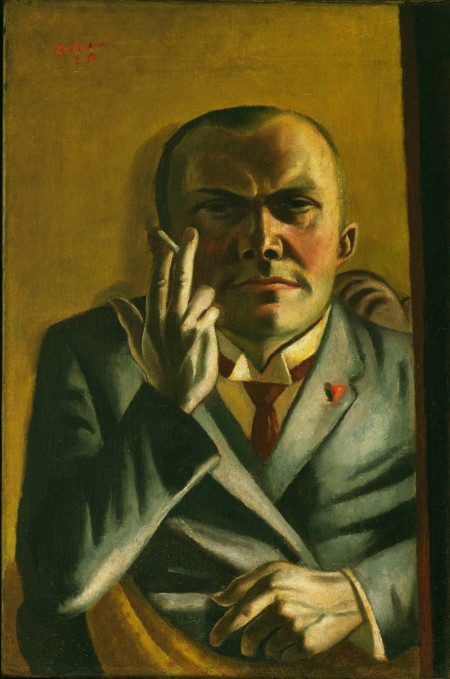

Self-Portrait with a Cigarette, 1923, oil on canvas, 23 ¾” x 15 7/8”. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Gift of Dr. and Mrs. F.H. Hirschland, 1956. SL.9.2016.18.1. © 2016 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn.

The earliest self-portrait in the show is the 1923 Self-Portrait with Cigarette. Beckmann is seated and fixated at something beyond the viewer. Instead of the shambling look of his final self-portrait, a plumpish Beckmann is dapper, dressed in a wing-collar dress shirt with a rose bud in his lapel.

Carnival Mask, Green, Violet, and Pink (Columbine), 1950, oil on canvas, 53 3/8” x 39 9/16”. Saint Louis, Bequest of Morton D. May. SL9.2016.24.3. © 2016 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Beckmann who was a keen observer of the world, keen and critical, had several other subjects that he returned to again and again—vaudeville, variety reviews, cabaret, jazz, and railway station restaurants. Beckmann also created scenes of a world gone mad.

Falling Man, 1950, oil on canvas, 55 ½” x 35”, National Gallery of Art, Washington, Gift of Mrs. Max Beckmann, S.L.9.2016.13.1 © 2016 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

In illustrating Goethe’s Faust II in 1943-1944, the artist drew many floating or falling men. In his 1950 Falling Man, a figure plunges to earth. Rewald is unable to resist likening this painting to 9/11, and muses that Beckmann would have been surprised to see this hellish scene become real. To carry the comparison further, flames are consuming skyscrapers, while the day is all blue skies and fluffy clouds, just like September 11thof 2001.

Quappi in Grey, 1948, oil on canvas, 42 ½” x 31 1/8”. Private Collection, New York, SL9.16.8.3. © 2016 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

The cosmopolitan Beckmanns were part of café society in Europe and in the U.S. In New York he and Quappi were habitués of the St. Regis and the Plaza bars whether they had the cash or not.

Beckmann began Paris Society in Frankfurt in1925. Originally it depicted the German elite, but in 1931 he painted over it with this scene of the reception for his March exhibition in Paris. He went back to the painting again in post-war Amsterdam. Rewald noted several marked changes between the two versions. The expression of the German ambassador, who hosted the affair, was changed from one, presumably, of celebration to one of despair. Also the artist distorted the visages of the guests. Not having seen the earlier version, I don’t know if the physiognomy of some of the attendees was changed to suggest their Jewishness or not.

Rewald included five landscapes (but no images were available). I was unfamiliar with this work, terra incognito. Painted from oddly high vantage points, four of the five are very tall (37 ¾” to 54 7/8”) and narrow (14 1/8”), similar proportions to the side panels of Beckmann’s triptychs.

Departure, 1932-33, oil on canvas, center: 84 ¾” x 45 3/8”; left: 84 ¾” x 39 ¼”; right: 84 ¾” x 39 ¼”. The Museum of Modern Art, New York, Given anonymously (by exchange), 1942. SL.9.2016.8.3. © 2016 Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York/VG Bild-Kunst, Bonn

Beckmann’s iconic work, Departure, 1932,1933-1935, was the first of nine triptychs that Beckmann would ultimately do. It was begun in Frankfurt in 1933, and after he was dismissed from the art school there, finished in Berlin.

The center panel shows the back of a king, nude except for a royal blue drape; he stands in a small rowboat. His head is turned to look back at the shore. His right hand is in a Vulcan salute, and he holds a net full of fish with his left. His queen holds a baby to her breast in a Madonna-like pose. There is a sense of serenity but also a hint that this might not be just an afternoon on the water, an interpretation validated by the side panels that are dark scenes of torture. On the left a blindfolded woman is tied to a column, her arms bloody stumps. Her legs are spread apart in a provocative pose, and the torturer wields a club. The right presents a nude woman with a child at her side tied to an upside down man. A bass drum player marches by, oblivious to what is happening beside him.

With the organizing principle of New York, Rewald has given us a look at Beckmann’s work, but also into psyche of his collectors who began to acquire his work in the 1930s, well before his arrival in New York. They were certainly brave souls.

–Karen S. Chambers

“Max Beckmann in New York,” Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, 10-00 Fifth Ave., New York, NY 10028;212-535-7710, www.metmuseum.org.