A careful visitor to the Cincinnati Art Museum’s very substantial exhibition of paintings, sculptures, furniture, documents, implements, and advertisements of many sorts might well leave with no clearer idea about what constitutes “folk art” than when he or she came in. What, exactly, are we looking at? We’re not even sure what to call it. “Folk” doesn’t really help, with its implications of culture-wide creation, and “naïf” doesn’t even come close. They can’t rightly be called “outsiders,” since they seem so close to the core of their cultures. Sometimes the makers of these works have been called “self-taught,” but the CAM’s show tries to argue against that, noting, for example, on one wall label, that the watercolors by Emeline M. Robinson Kelly “showcase the painting techniques she would have taught at the school she established for young women in Portsmouth, New Hampshire.” Works in this show without a clear attribution are not credited to “Anonymous,” but—perhaps literally—to “American School.” Folk art is like the pornography of the art world; perhaps the best you can say is that you know it when you see it.

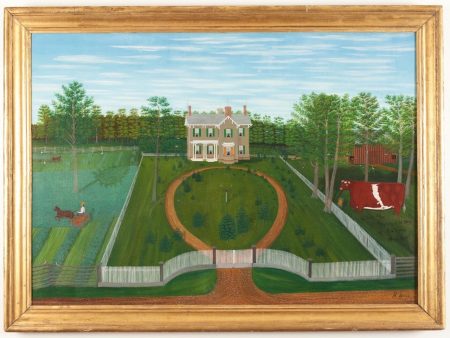

Henry Dousa (1837–after 1903), The Farm of Henry Windle, 1875, oil on canvas, 31 ¼ x 48 in. (79.3 x 121.9 cm), Courtesy of the Barbara L. Gordon Collection

The museum has brought together some sixty works from the Barbara L. Gordon Collection (quite a few of which have Ohio connections) and augmented them with outstanding material from local collections. From these works, one can begin to determine some of the qualities and conditions that make folk art look the ways it does, and feel so fresh. One quality of folk art is that we might well know more about the subjects of the paintings than about their makers. We know, for example, pretty much about what Henry Windle was looking for when, in 1875, the Washington Court House landowner caused the painter Henry Dousa to paint his farm. Windle wanted a picture of his world and no other: a two story house with cleared land up to the tree line, a circular driveway (with a pair of antlers mounted on a pillar in its center—a surrealist sundial?–serving a function lost to most viewers, but helping the painting keep up its conversation between the mundane and the strange), all surrounded by a truly extensive white picket fence. Windle’s world included plentiful signs of his agricultural success. On the left of the painting, a man is driving a horse-drawn harrow. Three other men are working his land in the background. A small fleet of woodpeckers and other birds proceed gently in rows above either side of the fence, but for all the dreaminess of the picture, there is a great deal of particularity, down to the gravel reinforcing the dirt road, the lightning rod running up the side of the house, and the painted window shades. On the right side, there is a huge brown and white bull who is fully annotated: “William Allen. Property of H. Windle. Five years. Weight 2500.” It is impossible to say what keeps the bull from running rampant—he towers over the fence that should contain him—aside from the implicit tribute to his perfect domestication. Painters of Dousa’s sort may or may not be itinerant, but their patrons are rooted in possessions which they wish to celebrate and have acknowledged. Windle’s name is an integral part of the painting: the whole work is a painting of what his name means. Windle’s interests in nature—and in nurture—are focused on the things that he owns. It is not landscape, but real estate.

Many of the artists in the show seem drawn to symmetry of design, perhaps as a way of demonstrating control over the potential wildness of the visual world. Folk art makes room for obsessiveness, in multiplicity of detail and in decorative enhancement. The anonymous fraktur celebrating the name of Eli Sweny in his twenty-first year, for example, is so filled with shapes within shapes and swirls within swirls that even when one looks hard for the letters of Sweny’s name, they are hard to find. Sculptor John Scholl embellishes his work with dozens and dozens of granulations just smaller than ping-pong balls, which carry the rhythm of the pieces, which look a little like pieces of machinery at rest. Everywhere you look on “Wedding of the Turtle Doves” (1907-15), it is festooned with tiny columns, a model of a fantastic piece of architecture that simultaneously emphasizes its openness and its enclosures.

Attributed to John Scholl (1827–1916), United States, The Wedding of the Turtle Doves, 1907–15,white pine, wire and paint, 37 x 24 x 17 in. (93.9 x 60.9 x 43.1 cm), Courtesy of the Barbara L. Gordon Collection

There is a serious stylistic issue in the flatness of the painted images—an aspect of the folk art vision that may help to explain how these works initially appealed to the mid-twentieth century eyes that rediscovered and rescued them, trained as they were on the conventions of the flatness of modernism. There is often very little chiaroscuro or even shadows of any sort to be found in folk works. (Of the two paintings said to be by Dousa, one is rich with naturalistic shadows and the other has not a single one.) This flatness helps create a sense of theatrical immediacy and artificiality; painted faces often look as if they’ve just been hit with a spotlight. Both the artist and the subject seem to be satisfied with a style that washes out whole categories of details. It turns out that chiaroscuro is not necessary for identifying a person or conveying character or property. It is often hard to tell the difference between a folk painter and a professionally trained artist who is not terribly good at capturing shadow—as the wall notes point out in the anonymous pair of portraits of the Grandin family: “These large, elaborate Cincinnati portraits are at the intersection of folk and academic painting.”

In one of the most interesting pieces of research that the show reports out, a wall label notes that Boston artist William Matthew Prior advertised that “Persons wishing for a flat picture can have a likeness without shade or shadow at one-quarter price.” The curators make the very fair conclusion that this suggests that to the mid-nineteenth folk painter, flatness was a choice, not an inevitability, and certainly not simply a sign of a lack of skill. The implication is that depth or shadow is more akin to, say, the type of frame you wish to purchase than an essential part of the likeness. It was a look, an economic option, and clearly, for some subjects and patrons, a preference. In Daniel McDowell’s remarkable “Still Life with Watermelon” (1860-80), the melon itself is as flat as a wallpaper design with a repeating pattern of seeds, but the white drapery on which it sits has as much modeling, shadow, and depth as the sleeve of a Renaissance Madonna. The painting seems to celebrate the pleasurable coexistence of these two different ways of seeing and representing.

Daniel McDowell (1809–1880), Still Life with Watermelon, 1860–80, oil on canvas, 17 x 24 1/2 in. (43.2 x 62.2 cm), Courtesy of the Barbara L. Gordon Collection

It is interesting to think that folk art may in part be defined by its ability to ask us to hold two fundamental principles in our minds at once. For example, the wall label describing two highly decorated horses (1840-50) by George Robert Lawton, Sr., notes that while they may seem “playful,” the “good condition of the horses…indicates that they were probably created as sculptures rather than toys.” I’m not positive that this logic is persuasive, but it asks us to think about folk art in terms of its possible purposes. Many things that we tend to call folk art are useful. One might certainly argue these days that even the most Apollonian artworks can be analyzed in terms of their function, but this tension plays out particularly interestingly in folk art. There seems, for example, to be a controversy over a remarkable “Chest of Chairs” (early 20th century) as to whether the eighteen miniature painted chairs in a small wooden box are salesman’s samples or children’s toys. Perhaps calling an object a work of folk art is to decontextualize it—though one could pretty easily make that argument about most things in an art museum. There is a striking “Rabbit Carousel Figure” (c. 1910), possibly carved by Salvatore Cernigliaro of the Dentzel Carousel Company, that is done with enough care to detail to make one think of taxidermy (another folk art medium?) and a play on scale worthy of Alice in Wonderland. One misses the carousel’s motion and the lights and the music, but at its core, the animal whose leap into the air is frozen and then skewered on a pole marks a place where playfulness and commerce intersect.

Attributed to the Dentzel Company; possibly Salvatore Cernigliaro (1879–1974), United States, Rabbit Carousel Figure, circa 1910, basswood and paint, 57 ¼ x 50 x 13 in. (146.1 x 127 x 33 cm), Courtesy of the Barbara L. Gordon Collection

The same might well be said of the exhibit’s three full-size standing wooden figures. The “Girl of the Period” (1870-85), attributed to Samuel Robb, exists to enhance sales, like many of her wasp-waisted descendants in the 20th century, but it’s hard to tell what she is selling: the clothes off her back or the small cigar she seems to be smoking? It is even hard to parse the gender dynamics of the figure: if she is selling tobacco, is she there to appeal to the New Woman or to the same old man, for whom the statue is the wooden prefiguration of the cigarette girl at a night club? It is similarly hard to know what to make of the “Dude” (1885-1900) standing next to her. He is an urban figure, but it is not absolutely clear which side of the law he is on. Who is supposed to see themselves in him? What would he make you want to buy? And what’s his pitch?

Unidentified Artist, United States, Dude, 1885–1900, white pine and paint, 79 x 22 1/2 x 22 1/2 in. (200.7 x 57.2 x 57.2 cm), Courtesy of the Barbara L. Gordon Collection

Some of the art is straightforward advertising, like the remarkable carved poplar “Dentistry Trade Sign” (c. 1890), which promises the same, perfect rows of teeth that every picture of an American actor or model features today. It is hard to separate images from advertising, then or now, and perhaps not worth our effort to do so. We see things that speak to us of desires, of fantasies, of things that we believe that we believe in. The exhibit includes a carved “Goddess of Liberty” (c. 1875), which it distinguishes from the other life-size figures by noting that we should not see it “functioning as an advertisement.” But why not? A short decade or so after the end of the Civil War, what is more essential to sell to its viewers than the abstracted version of the ideals for which the country fought and bled? There is no profit in being naïve about all the types of cultural advertising that goes on in today’s art museum.

I don’t think that the artists represented in this show would have been bashful about the connections between their works and the principles of salesmanship. Henry Windle certainly would not have been bashful about what the advertising aspects of the painting Dousa did for him. Another way to look at folk art might be to think of its practitioners as artists who are completely comfortable with their audiences and with what they are hoping to do for them. If there is a degree to which the artists have agreed to make wealth visible, they are also in the business to make themselves visible. If you liked, for example, James Bard’s painting of the “Steamboat Victoria” (1859), he has painted right onto the canvas not only the names of the ship’s ironworks and builders, but his own as well: “James Bard. NY. 1859. 162 Perry St. NY.” Give all credit where it is due. John Bradly did the same in his crowd-pleasing picture of a child holding her cat by one leg, signing it “J. Bradly. 128 Spring St.” If the archetypal American folk painting is Edward Hicks’s “Peaceable Kingdom” (of which he painted more than 60 versions in about 30 years), its message is that things normally opposed to each other get along, and various discourses—scripture, prophecy, and history—are in harmony. In the Peaceable Kingdom of folk art, the artist can lie down with the customer.

What sort of vision of America emerges from these paintings and sculptures? By and large, it is an America still firmly attached to rural roots and small-town values. If the “Dude” and the “Girl of Her Time” are almost surely urban pieces, they are among the exceptions. The great source of American wealth is still seen as land, and land and its products are depicted in many paintings, including the portraits. It is a world very close to animals, domestic and farm alike. The folk artist seems to imagine a natural world that has been improved and tamed, and has received the blessings of nurture. The remarkable “Bird Tree” (1885-1910), attributed to “Schtocksnitzler” Simmons, is its own peaceable kingdom, with ten songbirds perfectly at home in an imaginary, loopy tree, improving nature by their extreme comfort with each other and their complete lack of competitiveness, not unlike the animals on Windle’s farm. There is a “Bird House” (early 20th century) that has been carved out of a log in the shape of a man sporting a boater—a straw hat at a slightly raffish angle. Its mouth is expressively open; perhaps it is speaking or merely surprised to have birds fly down his gullet. This is art that requires a lawn, and a vision of nature that is happy to receive some help from the humans who have subjugated it.

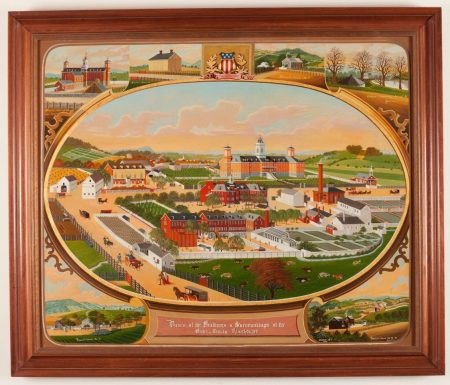

Charles C. Hoffman (circa 1820–1882), Views of the Buildings and Surroundings of the Berks County Almshouse, 1879, oil on tinplated sheet iron, 33 x 40 in. (83.8 x 101.6 cm), Courtesy of the Barbara L. Gordon Collection

It is hard to imagine a more robust celebration of rural values than Charles C. Hofmann’s “Views of the Buildings and Surroundings of the Berks County Almshouse” (1879). Despite its unprepossessing title, this large and complex work envisions practically the epic extent to which American culture has made a home for itself—and its citizens—in the countryside. We see an old couple, just arriving, leaning on each other. They are staggering partly from exhaustion from the journey that has brought them to the almshouse and partly from what they can see. Everywhere they look, people are working and playing; children are at school; in front of a building, there seems to be a civic debate going on. There is a sense of leisure that complements the workaday world here. This almshouse is not punitive about anything: while some people are riding in fine carriages, another man is relaxing on a pair of mules. There are insets of tenant houses—in this rural utopia, denizens of the almshouse can still be connected to property—and there are numerous buildings dedicated to the public good in this shameless advertisement for the good life, such as a hospital and a kitchen. Interestingly, it is a secular ideal: there are two churches, but neither occupies privilege of place at the center of this community.

So what’s not in this show’s vision of America? There is some recognition of the urbanization of the United States, but not much, and there is virtually no recognition of industrialization. The exhibit takes into account the significance of German-American ethnicity for folk art (without which you could not have the works that used to be called “Pennsylvania Dutch”), but otherwise there is very little representation of the dramas of immigration and its conflicts. With the exception of a dignified Native American chief extending his hand towards us with a fistful of cigars, there is not a single person of color to be seen in the main exhibit. The only African American face I could find at all is in a separate gallery with works culled from the CAM’s own collection of “American Folk Art: Watercolors and Drawings.” Here Mary Bruce Sharon’s “Grandpa’s Bridge” (1952) shows an African American nanny walking behind the children in her charge over the Suspension Bridge as it opens to the public. This is a significant omission and amounts to a serious erasure of many rich traditions of folk art done by African American artists from the 19th century on. To get a more inclusive vision of folk art, you must set out to find the Museum’s Gallery 219, where several “folk” works by, for, and about African American communities can be found. Some of this excision can be accounted for by our changing understanding of cultural production. The boxed collage of tropical sea shells celebrating the end of a long sea voyage called a “Sailor’s Valentine” (19th century), for example, used to be thought of as having been produced by homesick seamen. Now we understand it to be produced not by sailors but for them, executed by “indigenous women from Barbados,” as the label tells us. But the otherwise complete exclusion of work by persons of color is a true surprise and a considerable shortcoming of the show.

Attributed to John Hilling (1822–1894), Burning the Old South Church, circa 1854, oil on canvas, 17 ¾ x 23 ¾ in. (45.1 x 60.3 cm), Courtesy of the Barbara L. Gordon Collection

This is not to say that the show is completely devoid of representations of cultural conflict. Most striking is a trio of paintings attributed to John Hilling that show the looting and burning of the Old South Church in Bath, Maine, in 1854. The Church, which had originally been built by Congregationalists, had been leased to a Catholic congregation; a crowd was whipped up to a frenzy by agents of the Know-Nothing Party, and they marched into the church, desecrated it, flew an American flag from the belfry, and set the whole thing on fire. The sequence of paintings envisions this as a civic drama. In the first picture, the imposing church stands in what might be the heart of Bath. Well-dressed people stroll by, pointing out this and that, as if the church were one of the sights a tourist would have a natural interest in. The looters, in the second painting, are less well-dressed. The church’s windows are broken on the first and second floors and furniture is being pitched out of them. In the final painting, the building is wholly engulfed by flames. The ground glows red and hot cinders are floating into the air. In the background, the fire has spread to nearby trees and the roofs of neighboring buildings. In the foreground, two crowds confront each other. The one on the right carries an American flag, which–based on what we saw in the bell tower in the second picture—presumably makes them the burners. It is harder to tell who the people on the left are. Everyone is well-dressed, with most of the men wearing coats and top hats. But one might like to think that the crowd on the left is constituted of the citizens who oppose the burning, facing off against the Know-Nothings. In the background, we can see that the community still has the capacity to come together, as the local volunteer fire department is pumping water onto the enflamed roofs in the hope that people will still be able to live here when the violence has passed.

Unidentified Artist, United States, Gameboard, 1880–1900, wood, paint, and iron, 1 1/2 x 18 1/2 x 16 3/4 in. (3.8 x 47 x 42.5 cm), Courtesy of the Barbara L. Gordon Collection

Hilling presents a very different view of American communities finding their way than, say, does Hofmann in his rhapsodic idealization of the almshouse. But both are maps of America. Perhaps my favorite map in the show is the “Game Board” (1880-90) for some unidentified and possibly unique game. Like Chutes and Ladders, it has connected squares (color-coded), bridges connecting rows that become like pathways to the center, and networks of shortcuts. The game and its set of abbreviations are impossible for us to interpret, but it seems, like more recent games, to acknowledge a range of forces that make things go. It looks like there is supposed to be a spinner of some sort in the center and white squares numbered one through six suggest that the game would have had occasion for dice. Its flat colors are waiting to be filled out by adventures and symbolic narratives. It is open to the workings of chance, the usual force to influence and shape the rise and fall of fortunes. Like most games—and, apparently, like most folk art—it freely combines pleasure and utility. It is not for afternoons spent in solitude; the layout clearly suggests that it is a game that requires a small community to play it.