Like most of the country, I watched in shock and horror as white supremacists swarmed the city of Charlottesville in a menacing rally of racist anger and hatred. The violence they ignited ultimately reached a deadly turning point when a neo-Nazi plowed his car into a crowd of anti-white supremacist protesters, killing Heather Heyer. It was soon reported that the driver was from Ohio. Another Ohio man, a white nationalist with ties to the Cincinnati area, was later charged with the vicious beating of a black counter protester. These two men weren’t the only Ohioans among the mob of white supremacists, KKK members, neo-Nazis, and other white nationalists.

David Pepper, Ohio Democratic Chair, has referred to the state as an “epicenter of hate-group activity,” with the Southern Poverty Law Center ranking Ohio eighth in the nation for its number of active hate groups. Even more alarming, the FBI ranks it third in the U.S. for its number of reported hate crimes. These are sobering statistics from a state that was never part of the Confederacy, yet Ohio is now forever tied to Charlottesville’s history for the violence unleashed that weekend of August 11, 2017.

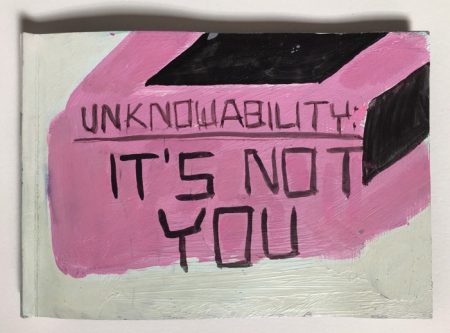

Sarah Boyts Yoder is a Charlottesville-based artist I had the pleasure to interview for Figure50.com more than a year ago. During that time, our conversation—via regular email exchange—primarily focused on her mixed media paintings and drawings. In describing her work she addressed the importance of “unknowing and unknowability” to her process, something that very much resonated with me as an artist.

In the wake of that horrifying weekend in her city, she replied to an email I sent, writing, “I think our human capacity for imagination and creativity are the best tools we have for confronting the certainty of hate / anger / scarcity / sadness / pain in this world.” Her statement offered an unequivocal clarity, a way forward in the uncertain times in which we live. As artists we know we can employ creative strategies to address, cope, and seek to remedy the ills of the world. Yet, even in doing so, the unknown is still what lies ahead. As an artist, Yoder is familiar navigating the unknown in her work. For this reason I wanted to revisit a dialogue through email exchange and speak to this concept within the context of Charlottesville, art, and the idea that we are all linked in some way.

What was it like returning to your studio after that horrific weekend?

Trying to go to that creative space and make my work, I had this paralyzing sense of ‘This doesn’t matter’ but also ‘This is the ONLY thing that matters’. Painting is so emotive. After the election in November I felt a similar way to how I do now. All the plaintive emotions I was feeling were met with comfort and solidarity in the paint. ‘Just paint’ was the mantra. I do most of my work on the floor, so I’m often kneeling or crouching, which also felt like the appropriate physical response. As an abstract artist who also has a relationship with text something new has emerged. Before I was content with the words and letters I include in the paintings being very ambiguous, in fact that was the point. Now I’m looking for and finding an outlet to be more pointed and outward facing with how I express my thoughts and my own resistance to the horrific things our government is trying to do, the way our society has been set up for so long. I think and hope that people can feel the emotions wrapped up in the paint and connect that to the words that give those feelings direction.

As you look for ways to be “more pointed and outward facing,” do the words and letters within your paintings become more specific, directly responding to what’s happening on a given day?

Yes, totally. Words matter.

In our previous interview, something you described really stood out in light of current events. You wrote, “I think another important concept for me is this finding, making sure there is always something to react to or against because the materials add unknown and unpredictable elements.” Obviously you were speaking about your art practice, but does this concept take on new meaning, perhaps in how you view your role as an artist in the current socio-political climate? Do you approach your work differently in the wake of what’s been happening in this country?

You could view the events on August 11th and 12th and the people who descended on Charlottesville (or those who were here already and came out of the woodwork) as ‘unpredictable elements,’ surely. How does one react now if the whole basis of your art practice is reacting to unpredictability? What if you didn’t seek out these elements, they came straight at your face and they scare and disgust you? If the unpredictable and unknown (which often, and certainly in this case, bring shock, sadness, real fear, shame, rage) ARE what is certain in our world and we don’t get to pick and choose when we encounter them (as I do in my painting practice)…what do I do? How do I react then?

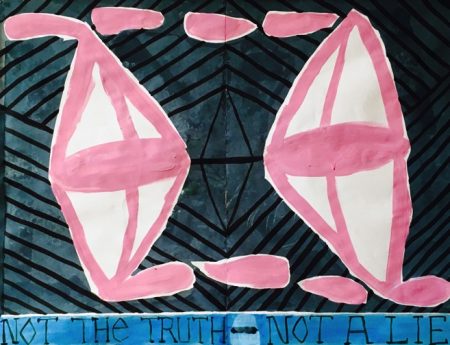

Something I want to say is that too often, we equate understanding with defining. This is about imagination. I believe as humans we can possess a complete understanding or recognition of something and never be able to put words, proof, or labels to it. And vice versa, we assign a thing, a person, an experience, a definition? It collapses and loses its potential fullness. As an abstract painter I am committed to the belief in the human imagination and its capacity for problem solving and empathy. Our imaginations rely on the unknown and in order for them to operate effectively they need our cooperation.

There is a space in between knowing and not knowing and it’s fertile ground. Too often, we encounter the unknown and we are frustrated. Our instinct is to turn away, to seek out what IS familiar. What if we could see that middle space (between familiarity and strangeness) as a joy not a frustration? A place to relax, look around, ask questions, make connections with each other and ourselves? If we can practice being there our imaginations expand, empathy grows. That’s the point of all art. And we need it now. A friend and fellow painter from Nashville, Jodi Hays, said in a conversation just after what happened here: “Without imagination we are stuck in ‘reality’ with no new perception.”

We are so queasy and uncomfortable, as white people, being in this in between space right now, specifically as it relates to white supremacy and what to do about it. ‘I’m not Richard Spencer, I detest and disagree with these hate groups and what they stand for, I’m not racist…right?’ We have to practice being in that place where we say ‘I know it’s here. I want to do something about it. I’m not Richard Spencer but I’m still unintentionally part of the problem, I look around and I see it. I don’t completely know what to do but I’m here for it and I refuse to get defensive and shut down. I commit to listening to and believing what I hear black people tell me about their experience.’ Our imaginations can help us here. This obviously takes empathy, which has its roots in the human imagination and desire to connect with others. Making art and experiencing it can help us practice this.

Art is like a shield for humanity, for civilization. Where capitalism and white supremacy and racism and scarcity flatten out people and experience, art gives us dimension again. A way to see how we can be fuller and expansive. I thought after the election, when I saw Moonlight, that like, things might still be okay. The world is still good if there are artists who are here, who made this piece of beautiful work, we will be okay.

Since the protests many Confederate statues have been taken down or covered. (I was surprised to learn Ohio has four, with one near Cincinnati that was recently removed.) Groups opposed to the removal see this as a collective attempt to erase history and even suppress artistic expression. Artist Mark Bradford responded to the calls for removal of Robert E Lee from Charlottesville, stating, “If this whole conversation is about the history of this country, then you have to talk about the history of this country. Don’t just leave these empty spaces. Contextualize the action.” As an artist in what’s become a sort of epicenter of this debate, has it affected your position regarding these monuments? Do you see a unified way forward for your city?

Mark Bradford is right about contextualization. I hear a lot of people say ‘What happened here in August, the visceral hatred, where did this come from? This is not Charlottesville.’ But if all this is not us, it’s also not not us.

I doubt the people who protest the removal of the statue and say it’s erasing history actually want the real history of the erection of those monuments told. In Charlottesville the Lee statue was commissioned in 1917 and dedicated in 1924 (not at the time of the end of the Civil War). It was placed practically in the middle of what was the vibrant black community in Charlottesville at that time. It wasn’t about honoring Confederate soldiers, it was about intimidation of the black families that lived and worked around and next to it everyday. There were hundreds of klansmen at the dedication service. Jim Crow was in full effect. That’s the context. Take the statue down. We’re creative enough to tell all of that story in this place.

I grew up in Texas, not ‘the South’, oblivious to the monumentalization of Southern generals and the glorification of the Civil War. For this reason, but mostly because I am white, I didn’t feel a thing when I walked by that (or any other) statue. I feel sorry that I never really gave it a thought because I know now how much it hurts, offends, and disrespects the black community, fellow humans who I share space with in every part of life. If the person standing next to you is hurt, offended and disrespected, don’t you try and find out why and fix it? Why is it that we find it so hard to listen to, really hear, and then act on the truths that black voices are speaking? White supremacy is real and it’s happening now and a part of it is this argument over how we choose to present history with these tired monuments.

I don’t really see a united way forward in Charlottesville. When I drive by it there are people with signs from either side every day. The city shrouds the statue then someone comes and rips it off at night. They are in a holding pattern until a legal hearing in October. Everyone is frustrated.

Confederate flags seem more ubiquitous than ever. Have you noticed a similar rise in Virginia? I follow the work of Sonya Clark, and find her use of the Confederate flag incredibly powerful. I wondered if you / other artists you know, visually respond to this symbol?

Sonya Clark had an exhibition in Charlottesville at Second Street Gallery last year. I LOVED the show. Her work is incredible. One of the many things it drives home is the fact that symbols are rife with layered meaning and history. The confederate flag is totally charged. To say a thing like that is ‘just a flag, about one particular history, honoring one moment and group of people in time’ is no longer responsible or even possible.

Flags are literally symbols. Any symbol can have different meanings to different people. But at some point symbols, like words, take on a shared meaning. When that happens the shared meaning and the shared language has to be acknowledged. To ignore or deny this shared meaning is either ignorance or willful denial. We’re at that point.

As artists, as people, WE MAKE MEANING. This is a beautiful and hopeful thing. It’s why I find hope in my work and in artists in general. But it also can take us apart as we assign OR DENY separate meaning in shared symbols and experiences.

Aaron Fein (www.aaronfein.com) from Charlottesville, is doing some great work regarding flags and symbols. His works in the series, Worry Flags, ultimately seek to ‘…highlight irreconcilable differences, while others speak to the possibility of new alliances.’ I love this idea as it speaks to our capacity to imagine reinvention and shifting a focus that was perceived to be set in stone.

How have other artists in Charlottesville responded to what’s happened?

Artists here have been mobilizing since last fall and the election. Making signs for the local Indivisible chapter, seeding downtown with posters and signs, making zines, fundraising through art sales donated and benefit concerts by local musicians. Artists and musicians are activated and engaged.

It’s been inspiring to see such a surge in socio-political art since the election. Can you recommend artists, art collectives, printers and other makers from your area selling their work for purchase online?

One of the best I can think of is Warren Craghead (www.craghead.com). He’s a fantastic artist and drawer who has been drawing Trump and his minions every day since he accepted the Republican nomination. You can buy the book here (http://retrofit.storenvy.com/collections/29642-all-products/products/21180692-trumptrump-volume-1-by-warren-craghead-iii). It’s both horrific and really satisfying. A sense of humor is totally a human evolutionary adaptation.

Mary Michaela Murray (www.marymichaelamurraly.com) is a talented painter who makes these beautiful, monumental works of dignified female statues from around the world, like a Lady Liberty in St. Maarten, The Angel of Independence in Mexico City, the Goddess of Democracy in Tiananmen Square, China. I love seeing these types of monuments enshrined in her paintings.

I have an exhibition coming up in October in Charlottesville at Studio IX Gallery called Forget Your Perfect Offering. The title speaks to what I definitely feel but also what I can see most artists, in fact most all of us, doing in the face of this unbelievable chaos in our world right now. A portion of sales will go to two hyper local initiatives (re. affordable housing and practical support to our immigrant friends and neighbors in Charlottesville) and there will be some prints for sale with money going towards those projects as well.

Our work as artists, as people, matters. And even though it might not be perfectly formed or large in scale, we can use it to help others and push to the front, the voices that haven’t been but need to be, heard most right now. Again, if all this is not us, it’s also not not us. Forget your perfect offering. Do what you can, with what you have, as often as possible. Resist every day…

When Houston’s floodwaters continued to rise in the wake of Hurricane Harvey, Yoder channeled her emotions into painting, creating a series she titled, Too Much Water. She saw a way to help others by offering each work for sale through her Instagram account, and quickly raised over $1,600 for the Houston Food Bank’s relief efforts. She means it when she says, “Do what you can, with what you have, as often as possible.”

For information about Yoder’s upcoming exhibition, and how you can purchase her work to benefit Charlottesville organizations, visit www.studioix.co and www.sarahboytsyoder.com . Follow her on Instagram @sarahboytsyoder.

Epilogue

As we wrapped up our email exchange, Yoder shared the following excerpt from The New York Times Magazine article about artist Chuck Close. Written by Wil S. Hylton, he reflects upon art’s enduring capacity for human connection:

It seems to me now, with greater reflection, that the value of experiencing another person’s art is not merely the work itself, but the opportunity it presents to connect with the interior impulse of another. The arts occupy a vanishing space in modern life: They offer one of the last lingering places to seek out empathy for its own sake, and to the extent that an artist’s work is frustrating or difficult or awful, you could say this allows greater opportunity to try to meet it. I am not saying there is no room for discriminating taste and judgment, just that there is also, I think, this other portal through which to experience creative work and to access a different kind of beauty, which might be called communion.

–Kim Rae Taylor

Hylton, Wil S. “The Mysterious Metamorphosis of Chuck Close.” The New York Times Magazine, 13 July 2016. https://www.nytimes.com/2016/07/17/magazine/the-mysterious-metamorphosis-of-chuck-close.html