As you walk into Caza Sikes in Oakley to see the ambitious mini-retrospective of Cole Carothers’s paintings, you are greeted by a large scale self-portrait called “Livestrong” (2005). In it, he is standing in what for many of his paintings is his home away from home, the corner of his studio. It is brashly hung—it is the work of his you’re likely to see first on your way in—and yet it’s also unprepossessing, almost shy. There is no label to identify it, and though we can see the artist’s torso and hand, his face is largely hidden behind two mat sample corner pieces, taped together. He is looking through the space between them. With the one eye visible to us, he is framing a view. It might be of us, but I wouldn’t count on it. He is seeing, I should think, another deeply satisfying example of the way all things in the world can be framed by squares and rectangles, how they can have order imposed upon them through the effort, puzzle, and pleasures of geometry.

If we know nothing else about Cole Carothers’s work, we are likely to know that he does paintings that are windows, and depicts windows that are paintings. That is a perfectly good place to start, and there are plenty of such works on display at Caza Sikes, a recently opened gallery in Oakley. An important conceptualization of the categories for American representational vision was set out in 1978 by John Szarkowski for a photography exhibit at MOMA called “Mirrors and Windows.” In it, Szarkowski argued that American artists tended to either show themselves (mirrors) or were engaged with the world around them (windows), though he wisely noted that the categories are not mutually exclusive. This is how I take all the visual, imaginative, and calligraphic busy-ness that goes on in all those rectangles Carothers places at the border between his indoor and outdoor worlds in many of his canvases. Taken together, the pictures at Caza Sikes suggest that Carothers is a habitual (and infectious) formalist, a mischievous realist who makes a carefully curated version of reality look random and haphazard, and—perhaps surprisingly–a visionary for whom the material world is only the beginning. It’s hard not to be impressed.

The show consists of some thirty substantial paintings of various sizes (some virtually monumental), along with perhaps a dozen or so much smaller works, many less than 2 inches by 2 inches. The works were selected by the gallery’s curators and managers along with the artist’s help, so there is something authoritative about the collection as a whole. There is a particularly well-illustrated catalogue that accompanies the exhibition which contains an essay by Karen Chambers, who contributes regularly to Aeqai. It is only the third show at Caza Sikes, which opened this year on September 15.

It is the show’s contention that Carothers’s work was shaped by his response to the artistic and intellectual dilemmas of starting out in painting towards the end of the 20th century, a time when painting seemed to have to acknowledge that it had a very, very mediated relationship to “reality.” Everywhere you looked, you saw not so much other landscapes but other painters’ solutions to painters’ problems; you saw other paintings. The painters and the types of paintings an artist might admire are blocking his view. In the mid-1990s, Carothers painted rooms whose windows were so literally paintings that they had actual framing materials collaged onto the canvas. In “Bologna Street” (1998), we look out through a window that is part picture frame from the vantage point of an enclosure that does not seem to be securely enclosed; it is part room and part terrace. The design is intensely symmetrical, with a few things weighted towards one side or other to break up the rigidity. In these earlier works, symmetry was a device that even when used with critical intelligence was not always the artist’s friend. Like many of the early Renaissance paintings of which Carothers seems so fond, the painting has a fairly strict perspectival scheme. The viewer is rooted in a single spot, but in an airless and almost oppressive way. These early works of Carothers are like devotional paintings where we offer our devotion to the painting within the painting. Because they are, at the core, highly illusionistic ways of looking at unnatural things, they also suggest Carothers’s ongoing interest in the surreal; there is an element of uncanniness that tends to haunt many of his works that depict naturalistically rendered scenes.

One of the earliest major paintings in the show is “Storm in the East,” from 1986. It is not a painting about a storm—Carothers is only very rarely interested in capturing a fleeting moment of time—but about a room, a space. The storm, such as it is, is barely visible through a slice of window. But it is interesting that the window is already there for Carothers, as early as three decades ago, adding space, as a Renaissance portrait might have, to a tight and narrow enclosure. On one of the two tables, there is an open packing box into which we cannot peer. While it might be a scene of moving out, I prefer to think of it as a scene about moving in—to a space and to a set of artistic concerns that would continue to occupy him as a painter for many years. The “storm in the east” might even conceivably refer to the picture pinned up on the wall, a reproduction of Gentile Bellini’s fifteenth century “Seated Scribe.” While the young man may be writing a diplomatic message, his notebook appears blank and he has the intensity of concentration of an artist sketching. The storm from the east might be the new conventions of depicting space that are going to be coming to Europe from Asia—flatter abbreviations of space while Europe was exploring and mastering techniques of opening space up through visual perspective. Situated over the face of the seated young man in a turban is a sort of bullseye—the crosshairs of a rifle sight or perhaps of a camera rangefinder. Either way, it reminds us of the mediated ways in which we encounter artwork, let alone reality.

It is an interesting pinup for an artist’s studio—and “Storm in the East” is, in this exhibit, Carothers’s earliest run at one of his favorite and most significant scenes, the corner of the artist’s studio, with the Bellini occupying the place that is often taken by a second window, or some other rectangle ready to be painted on and looked at, or through. There are the conflicting schemes of perspective—the tables and the tiled floor don’t seem to sit in the same space. There are the blandly, almost institutionally painted walls that on second look have far more painterly depth and nuance than first appears. There is the brush on the smaller table, which stands in for the absent artist. And everywhere, there are interrupted geometries—a composition made up almost exclusively of rectangles and trapezoids–plus one banana, which is turning brown in real time.

Carothers’s aesthetic is strongly shaped by traceries of geometries, sometimes bold, sometimes febrile, that he perceives or imposes everywhere he looks. It’s how he sees, and how he builds his compositions on a canvas. It’s a quality he shares with an artist like Diebenkorn—perhaps originally linked through a common interest in adapting Matisse—who is on the honor roll of artists important to Carothers listed in a footnote to Karen Chambers’s catalogue essay. The list is quite long and quite honorable, though it is one to which other eyes might add still more names, including the artists whose work tries to find the romance in the severe four-square look of American architecture (such as Childe Hassam) or who engage in the push and pull between nature wild and nature tamed (such as Inness). We can see these forces in his work in a painting like “Little Garden” (2005), a toolshed’s-eye view of a suburban backyard where two small greenhouses face a patch of yard that looks like it is being prepared for planting. Three rusted wheelbarrows are leaning up against a stone wall. The picture is one of many reminders that Carothers habitually resists the picturesque, both in subject matter and composition. Looking at the painting, one wonders a little bit just which “little garden” is being highlighted, the patch of dirt next to the well-trimmed hedge, or the glass houses where, presumably, the garden’s seeds have been started. The intrigue of glass is eloquently captured; it is mostly transparent but often shows at least a hint of reflection. The tiny buildings consist of frameworks of perpendicular lines braced by triangles, vivid geometries amidst the possibility of gentler curves in nature. The top third of the picture shows trees whose leaves are just starting to emerge. They are painted perhaps with less assurance—Carothers has been turning his attention to capturing natural forms in very recent years with works like “Vines” (2016) or “Before 3 Shots” (2016)—but it feels like an important choice on his part to include them at all: many of his earlier landscapes feature a pretty smooth horizon line, erasing all the natural forms.

For me, the core of the retrospective portion of the show is the selection of paintings done in, and of, his studio. Typically, they depict his studio as a corner. It’s where he goes to paint, the place where distractions end and creativity happens. In this corner where two walls come together–often at a highly acute angle–there are pipes, partly wrapped (insulation?) and often in the process of becoming unwrapped. There are tables where he allows us to see the artist’s clutter—brushes, tubes of paint, containers that probably hold solvents and cleaning agents of various sorts–with things carefully put back in their places, more often than not. The walls—sometimes painted, sometimes covered with wooden panels or drywall, sometimes with chips of paint peeling off brick—look flat and unprepossessing at first, but often turn out to have been rendered with painterly depth and complexity. And then, of course, there are the windows, often two facing each other (allowing in at least two different sorts and sources of light), with curtains or not, with ledges empty or full, open or closed, framing things as surely as the two taped mat corners do in his self-portrait. This is his most habitual painterly landscape, and possibly his psychic landscape. It is a vista that shows up again and again, with the insistence of dreams. I don’t think it’s out of line—and I certainly don’t mean it disrespectfully—to suggest that there is something both confining and liberating about this corner. There’s no place left to go and nothing left to do but paint. Sometimes it looks like the painter is imagining himself as sequestered, if not actually confined. Medieval monks, however dedicated they were to their work, may have felt the same way looking out their cloistered windows. This is the corner he chooses to paint himself out of.

“Fans” (2003) is a classic version of the studio corner. Out a window with a shade partly pulled down, we see the brightest and most colorful part of the painting, a vista of an industrial site; Carothers has an interesting relationship with unlikely subject matter such as light industry and suburban detritus, and gives a particular liberty to his palette for such things. (“Sixth Street Viaduct” [2007] will take as its central subject highway cones, masses of abandoned cars, and even overflowing dumpsters, all rendered in the brightest colors.) On and under a table are many of the artist’s usual cast of characters: bottles, jars, and containers of the sorts of stuff you would be wise to keep under tight control. Taking the place of the second window is a romanticized, if grey-brown, urban vista which is as likely to be Italy as anything else. To the left of this panoply of baroque stone, there is a thick grey rim, making it seem as if we are looking at his exotic street scene out a casement. But there is a rim of shadow under the city view, which makes it seem as if this view is actually of a second painting, a painting within the painting. The picture as a whole raises questions about where the artist is when he works, and the answer, whichever way we look at the second “window,” is that the artist is both firmly here and yet also far, far away. It’s worth remembering that the title of the piece is “Fans,” calling attention to the two fans on the floor, one that looks like it’s for venting noxious industrial fumes, and the other a white plastic personal window fan. As the artist puts away the tools of his trade, he has succeeded in making himself in two places at once.

Windows and mirrors: Do we look through things to an outside world, or do we look at the surface of things, and see a world—and a self—that the artist produces? We can enjoy some of the same perplexity in “Bare Necessity” (2000). A canvas is sitting on a table in a space that is both readily recognizable—we are in the corner of the artist’s studio in what seems like finely dispersed late afternoon light with a window on one side and a sort of faux window on the other—and yet impossible to comprehend rationally. It is another of Carothers’ paintings with incompatible perspective schemes at work, putting us in a space that exists only when looking at the painting. The walls that look like they meet in a corner might, on the other hand, be giving way to a corridor. A completed painting sits on a table, held rigidly upright by unimaginable forces. And on that canvas, which introduces altogether other schemes of perspective, we get what looks like a reflection of the room, except that cannot really be. On the distant back wall of that painting is another window, looking out into the night. It is not even clear to me whether we are looking at the front of the completed painting within the painting or at its back.

I don’t think it’s going too far out on a limb to think that these studio paintings are self-portraits of an artist and his vision. They are in touch with the elements of surrealism and the uncanny that were present in some of the earliest pictures in the show. To the viewer this may be nothing special, Carothers seems to be saying of this relatively barren corner where he works, but to the artist it’s the space of the imagination, who just paints what he sees. This is why it’s a little breath-taking and risky to do what he does. There is a placidity in these works that is entirely misleading. Under it is a wildness that is the other side of the coin of the works’ extreme restraint.

It’s possible even to wonder at what cost Carothers achieves his placidity. The corner of his studio is disarmingly neat and clean. I have had some very expensive house painters leave more mess behind them than Carothers portrays of his working space. This is complemented—and perhaps relieved—by “Journeyman’s Sink” (2008), which seems an homage to the effort to maintain order in a painter’s working spaces. It is a vaguely anthropomorphic view of a sink that will never get truly clean. There is a bar of soap in the awful pink color that some bars of soap have (especially when they have been put to work scrubbing unusually dirty hands), and a nail brush, and some cleaning product in a packet. It is a reminder of the earthiness of the artist’s work: it’s a dirty life and a dirty job capturing the alternate realities he sees.

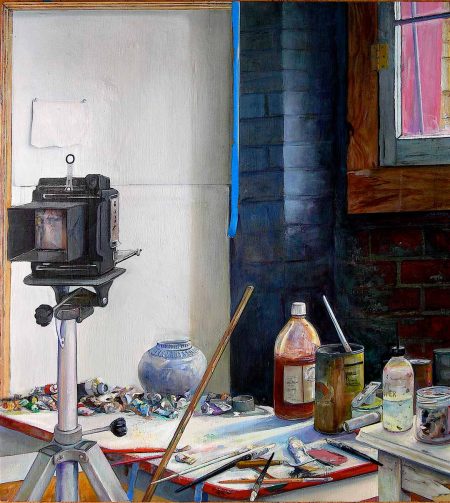

The masterpiece of the studio view in this show is “BIG” (2006). It features what is by now a familiar cast of characters, starting with the corner view, and including one real window and one small square (a scrap of paper or canvas?) pinned to the adjacent wall, taking the place of the second window. We’ve got the blue and white Chinese vase (that often shows up as a brush holder) and the bottle that looks like it’s holding ketchup or sriracha. There is the shimmering rust of the tin can and the luminous bottle of solvent. Brushes are scattered, pointing every which way. There is a wonderfully-rendered heap of tubes of paint, telling us where all the artist’s magic comes from, that reminds us that Carothers’s hyperbolic realism could be just one step from the abstraction of pure color. What’s different is the foreground where, mounted on a tripod, there is a 4 x 5 press camera with a bellows that we cannot see from this angle. Facing us is the ground glass plate that the photographer would use for composing and focusing. It is, in some ways, the extremely fancy version of the two taped mat corner pieces from “Livestrong”: its purpose seems to be to help the artist frame his subject matter. Part of what is remarkable about this painting is that in it, Carothers has given us an abbreviated self-portrait. We see his face in the ground glass as if it were what the camera is seeing, but it turns out to be just a reflection, a mirror, not a window. He is somewhere behind the camera, not in front of it. It is a self-portrait of an invisible artist. But just as he is not standing in front of the framing eye of the camera, neither, really, is anything else. The camera is pointing at the empty space of the wall. This, the painting seems to suggest, is the true source of the artist’s realism. He looks off into empty space and populates it largely from his imagination. If his style is intensely realistic, it is nonetheless not at all clear what reality is. It is, in any case, not necessarily what is tangible. The drama of this painting comes from his wanting us to recognize that the painter is a visionary. In his own little corner, he can paint what is not there.

I don’t want to give you the sense that Carothers doesn’t get out much. There are a fair number of outdoor paintings and there seem to be more and more of them as this career retrospective draws closer to the present. In one work, “According to Code” (2000), he works at merging the qualities of the outdoors and the indoors. Superimposed over a panoramic landscape, Carothers has painted a contemporary architectural space with a floor and ceiling and vertical supports, which may or may not be holding floor to ceiling windows. It is hard to say what the dimensions of this room are because its layout is made puzzling by a riot of lines suggesting, once again, more than one perspectival arrangement. It looks like a millionaire’s treehouse, an imaginary space from which landscape can be appreciated. But isn’t this where artists situate themselves most of the time?

The show as a whole suggests that Carothers’ work has changed in the last five to seven years. His painting style is looser. He is far less concerned with glazes—there is something opaque and almost chalky about the painting style in the newer work–and more of his marks are gestural; we may still be in rooms, but there are no ruled lines. I am especially interested in the ways that the new work continues to develop his interests from the older work, reinterpreting his own body of work in new styles. “Raw” (2014), for example, seems to be in direct conversation with his earlier career concerns. We are looking into the corner of a room—quite bare and certainly not yet equipped to be an artist’s studio–but we have a relaxing distance from it. There is still a window and a faux window, in this case a fictive version of the bright sunlight streaming in. (The light coming through has more panes than the glass that lets the light in.) There are elongated geometries everywhere we look. There is still more than one type of perspective; to the extreme left of the painting, there is a door, open just a crack, that leads to a long corridor in some other space. But while there is still something spooky about the door and the long dark hallway behind it, the looseness of the work makes it more provisional.

In “Light Dissolves” (2015), we seem to be in a barn. A heavy wooden shutter has been swung open, framing—as always—our view. But we are only looking at one frame at a time. It is hard to say whether we are overlooking a garden or a profusion of wildflowers. They are random and indistinct which argues for wild, but there seems to a wall in the middle distance, which suggests property and purposefulness. The world of nature is here made of color, not of line; this is what happens when you give in and just squeeze those paint tubes. It is among the most impressionist of Carothers’ paintings on view; perhaps the point of the title is that light dissolves form. But there’s more dissolving going on. The sun is hitting the very top of the barn shutter so brightly that the thick, bulky wood is starting to dematerialize, as if it were sublimating directly into the atmosphere. The frame itself is capable of disappearing. As the camera pointing at the blank wall told us in “BIG,” we are once again back to a world where the tangible is as much a feint as it is an end in itself. A visionary impulsiveness outweighs his habitual carefulness. Materiality is willing to sacrifice itself for a few breath-taking moments in Carothers’s most recent work and allow that there are spiritual qualities that rulers can’t measure or confine.