Christian Boltanski, Animitas blanc, île d’Orléans, Canada, film couleur, 2017 (installed and viewed) © Christian Boltanski, Adagp, 2017. Courtesy Collection Marin Karmitz, Paris

Bittersweet is a term often used to describe simultaneous positive and negative feelings. What I felt recently upon leaving the exhibition Étranger Résident: La Collection Marin Karmitz at Paris’ La mason rouge requires a stronger term, something connoting being both energized and enervated, for quite different reasons.

Since it opened ten years ago La mason rouge [lower case not a mistake] has been one of my favorite exhibition venues in Paris, or for that matter anywhere. I always look forward to seeing what has been accomplished in this relatively small and somewhat labyrinthine space with a tiny cafe and bookshop, and am seldom disappointed.

I had the opportunity to view the current exhibition while in Paris recently for the World Congress of l’Association International des Critiques d’Art (International Art Critics Association). During the Congress, AICA arranged a several exhibition and studio visits and to my delight La mason rouge was scheduled for the first stop (breakfast) of a day long bus tour. If you ever have been to the Centre Pompidou you probably walked by a movie theatre called mk2; they’re all over Paris. I learned only on this trip that the mk stands for Marin Karmitz, a Romanian refugee who became a filmmaker in Paris in the ’60s and in 1974 founded a very special sort of cinema, celebrating the art of film not only exhibiting films but promoting film production by promising and established filmmakers (particularly independent or “auteurist” films), and selling and distributing the films. Among those he enabled are Chaplin, Godard, Malle, Renais, Chabrol, Truffaut, Tanner, Loach, Kieslowski, Hallström, Frears and Van Zant. He was instrumental in shaping modern world cinema as well as helping create its audience. Wherever mk2 cinemas have opened in Paris they have transformed the surrounding district, not only showing films but supporting them with related books, lectures, photography exhibitions and music performances. Additionally all foreign films were shown VO (their original version, with subtitles rather than dubbed into French as was then the custom).

The maison rouge is in the Bastille neighborhood, in which Karmitz’s first cinema was opened. Its exhibition of Karmitz’s collection is part of an annual cycle of exhibitions of private collections, including that of Bruno Decharme in 2014, Artur Walther in 2015, and Hervé Di Rosa in 2016, continuing with Debbie Neff’s collection, Black Dolls, in 2018. Karmitz patiently assembled his collection over 30 years and, as exhibited a La mason rouge, it consists primarily of black and white photography mostly from the second half of the 20th century, interspersed with exquisite examples of pre-Christian tribal sculptural objects from around the world, a small collection of paintings and sculptures by Jean Dubuffet (given their own small room), a handful of other paintings and drawings and compelling large installations by Christian Boltanski, Annette Messager, Chris Marker and Abbas Kiarostami, also predominantly black and white.

A photographer and photography curator, I’d previously seen some of Karmitz’s photography collection exhibited at les Rencontres d’Arles in 2010 (Traverses); but wandering through Resident Alien at La mason rouge was especially thrilling for me (and I’d advise anyone interested in the medium to hurry over to Paris and see it before it closes in late January). The show is installed often in long dark corridors, some with small intimate rooms opening at intervals, some opening onto larger campos (reminding me, in hindsight, of Venice, with surprises at every turn). Surrounded by some of the greatest photography of the 20th and 21st centuries, like a kid I ran to get a fellow curator from Sweden to show him “Look, he not only has Petersen but Strömholm” or pull an American curator over to see the work of the underexposed, American-born, Canadian David Heath.

It seemed to unfold like a personal letter, and not unlike a challenging film. Indeed Karmitz writes of the exhibition “I entered into this project the same way I would write a scenario before bringing it to the screen. In fact, many similarities exist between this project and the making of a film… I wanted to tell a silent story with a lot to say, a story with images instead of words.” And, of course, as with most personal art collections, a portrait emerges of the collector himself, usually one among many possible portraits depending upon the work selected and its arrangement. But here, the portrait is nearly complete, as the mr exhibition presents virtually the entirety of Karmitz’s collection, almost 400 works.

The title, Resident Alien, gives a clue to this self-portrait. English rather than French, it likely describes the nine-year old son of a Jewish family from Bucharest in exile, become a citizen of France and an eventual Parisian cultural institution (even awarded the medal of the Legion d’Honneur), just turned 80… yet still not French. We’re told it also references a passage in Leviticus, the third book of the Jewish Torah, in which the divinity puts humanity on notice “…for the land is mine; for ye may reside as strangers and sojourners with me”, reconciling humans with the knowledge of their temporality, merely passing through this world (as are we visitors passing through the exhibition). And, no doubt, it is meant to remind of the contemporary political situation in France and Europe respecting the current influx of refugees.

The entrance to Resident Alien is an installation created by Christian Boltanski: a revolving door made of large plastic fringes on which are screen-printed extracts of F.W. Murnau’s 1924 film The Last Laugh, a film which largely eschewed the title cards of spoken dialogue or description that characterize most silent films, in the belief that the visuals themselves should carry the meaning.

Many of the artists whose works are presented in Resident Alien are themselves transplants. The first work encountered is André Kertesz’s photograph East River, New York, 1938, of a bearded man dressed in black clothes and hat sitting next to a mooring post, turning to look at it momentarily as though recognizing it to be a human head absent all identity. Kertesz was a Hungarian emigrant, also Jewish, who lived and worked a highly productive decade in Paris (among to the surrealists) before moving to New York in 1936 to escape increasing anti-Semitic persecution in France. But he always felt out-of-synch in New York, and America was slow to appreciate him. It’s easy to interpret the image functioning as a self-portrait (for both Kertesz and Karmitz)

André Kertesz, East River, New York, 1938

© Rmn – Grand Palais, Courtesy Collection Marin Karmitz, Paris

The next work encountered is a large number of images on both sides of a long corridor by Israeli-born American photographer Michael Ackerman, who worked for the Paris-Based agency Vu and is greatly admired in France. The work, like much in this exhibition, is dark, visually and emotionally, and “captures the brutal grace of damaged individuals and shifting urban landscapes.” It leads us to a variety of works exploring blackness and the legacy of slavery by another American artist, Kara Walker. These two artists’ take on the American experience funnel us to a space set aside for prints and projections of Lewis Hine’s earlier documentations largely of European immigration to America and child labor and working conditions for the poor in the America of the 1920s.

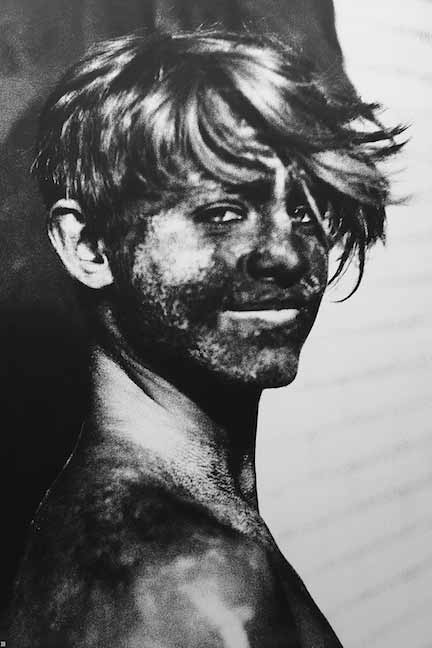

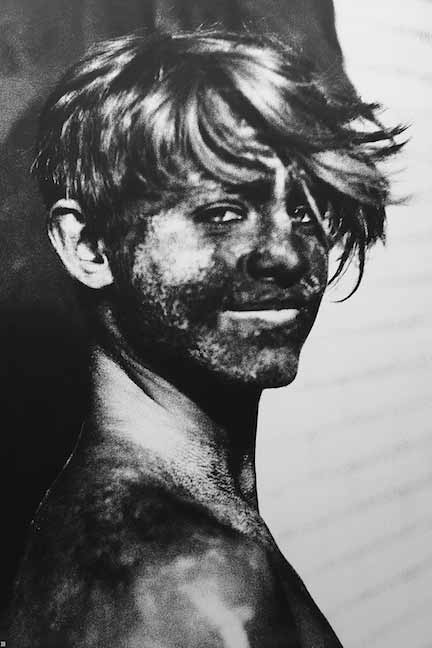

The corridor ends with a large print of Karmitz’s first acquisition as a collector: a 1938 photograph of a smiling, soot covered young miner by the Swiss photographer Gotthard Schuh. Schuh is regraded as formative in the development of modern photojournalism and later a personal style called “poetic realism” (an echo of early “documentary expression” in the US). The photo inspired the poster for Claude Chabrol’s 1988 film Une Affaire de Femmes.

Gottard Schuh, Grubenarbeiter Belgique (Belgian Coalminer), 1937

© Gottard Schuh, Courtesy Collection Marin Karmitz, Paris

The exhibition then turns and broadens into a wider space, populated largely by Europeans. Unknown to me in this space were a book by Lithuanian photographer Moï Ver, Kibbutz in Eastern Europe, and related, familiar images by Roman Vischniac recording poor Jewish communities in Central Europe (accomplished despite Nazi laws forbidding a Jew from acquiring a camera and film or photographing in the streets). Jewishness is an omnipresence through the artists of the exhibition. This historic work yields to exquisite work by the well-known Czech-born, resident French (and also itinerant) photographer Josef Koudelka, engaging his first major subject: European gypsy communities in the 1960s.

Another Boltanski piece (he has four in the exhibition, that I counted), Resistors, catalogues the faces of anonymous, executed German resistance fighters, and is close by a L’Inconnue de la Seine (Unknown Woman from the Seine) by Man Ray, a bronze sculpture utilizing the ubiquitous death mask said to have been cast by a pathologist in the Paris morgue of a woman drowned in the Seine. Ray was born Emmanuel Radnitzky in Philadelphia, but the family change the name to Ray due to anti-semitism in the US before “Manny” moved to Paris. Earlier he had used the same mask in a photograph, superimposing open eyes over the mask’s closed eyes.

Struggle and resistance continue on a facing wall with two and three-dimensional work by the identified Catalan, Polish and German artists Julio González, Maryan S. Maryan and Otto Dix, all in different ways victims of the Second World War. A drawing by Nancy Spero references her anti-Vietnam War activism and more explicitly feminist resistance. These face two large multiple grids of photographic self-portraits by German Deiter Apelt proposing his battered body next to Françoise Janicot’s self-portrait Cocoon of her body totally bound with rope.

It’s a rather depressing space which terminates with French photographer Antoine d’Agata’s color reflections Auschwitz; then, as the room began, with Gottard Schuh, who in later years retreated from the active world of reportage to promote the work of other photographers as a picture editor and traveling in South-East Asia to make more inward, subjective images.

Two works lead us to the exhibition’s signature corridor: a rough Alberto Giacometti painting, Nude, depicting a woman’s naked form superimposed over a man’s clothed trunk, oddly reflected in American photographer Duane Michaels’ directorial narrative The Spirit Leaves the Body.

The corridor itself is long and dimly lit, with seven openings on the right to seven small rooms, while on the left side are glassed niches containing single objects: first a ceramic sculpture Personage by the Catalan Joan Miro, then six artifacts from Mesoamerica (including Mayan and Alaskan Okvik cultures) dating back to pre-Christian times. The niches and room entrances glow in the darkened hallway, reminding of a cinema, or perhaps monastic cells.

Even in the well lit rooms, darkness pervades the imagery inside. In the first are featured the powerful Swedish photographer Christer Strömholm’s black and white portraits of the transvestites and transsexuals of Paris’ Place Blanche red-light district in the late 1950s and early ’60s, paired with a George Groz painting, drawings by Polish sculptor Alina Szapocznikow and the Swiss painter Ferdinand Hodler (a preparatory sketch for The Disappointed Should or Weary Life), along with another Strömlolm image, a self-portrait. A self-reflective feeling pervades.

Strömhol’s influence continues into the second room with one of his students Andres Petersen’s intimate recording of the patrons of Hamburg’s working class Cafe Lemitz, and “ghosts” from the short-lived photographic career of Chilean photographer Sergio Larrain, photographing street children in Santiago and the dockland of Valparaiso.

The third room is given over to the French “Art Brut” (raw art) artist Jean Dubuffet’s early slash and scratch impasto paintings; then the fourth to American photographer W. Eugene Smith, best known for his photo-essays – including his extended portrait of Pittsburgh at its sooty industrial peak, extracts of which are here along with his images of jazz musicians and surreptitious shots from his apartment window in New York – and the technical brilliance of his prints, with deep, rich blacks and shimmering highlights.

The logical segue occurs in the fifth room with the work of the brilliant Roy DeCarava, also photographing the world of jazz and many other aspects of New York’s post-war African-American community. DeCarava virtually invented a visual language for blackness in American photography. The work is juxtaposed with that of Saul Leiter, photographing in NYC in the same period, developing his own photographic language: an almost jazz-like play of reflections, silhouettes, blur and framing. Leiter, who studied to be a rabbi before abandoning his studies and moving to NYC to become an artist, was persuaded to pursue photography by Smith (fourth room) and is often identified as being among the “New York School” photographically. The two bodies of work are offset by Profile (which, unfortunately, I can’t remember) by the German Bauhaus artist, designer and choreographer Oskar Schlemmer, much of whose work was destroyed by the Nazis as “degenerate art”.

Another “New York School” photographer, Leon Levinstein, shares room six with Philadelphia-born, Canadian émigré Dave Heath, both solitary wanderers whose mannered imagery evokes filmic depictions. Levenstein likes to get close, often employing low angles, in visual confrontations with the city’s humanity, while Heath explores isolation, often depicting non-connecting subjects in a pervasive, almost theatrical darkness of alienation or despair. Abandoned by both parents before he was four, Heath grew up in foster homes and an orphanage, profoundly affecting his artistic sensibility, as did time spent studying with Eugene Smith. Despite major museum exhibitions and Guggenheim Fellowships in the early 1960s and his moving 1965 monograph A Dialogue with Solitude, for most of the rest of his life he endured obscurity. Finally, a major retrospective of Heath’s work opened at the Philadelphia Museum of Art in 2015 and toured until just recently. He died on his birthday in 2016.

Dave Heath, Vengeful Sister, Chicago, 1956 © Howard Greenberg Gallery, New York and Stephen Bulger Gallery, Toronto.

For me, loomingly powerful in absence, is another “New York School” photographer, the Swiss-Jewish immigrant to the US (and then Canada) whose own gritty and seemingly depressing (for the time) depiction of America in his book The Americans, probably has had greater impact on the medium than any other photographer of his century (first published in 1958 in France, as US publishers found the work too dark). He was listed among the artists in the exhibition but I never found him. (Since then I have identified a lone, atypical photograph of Frank’s in the exhibition: a night image of silhouetted apartments against a dark sky, with a single, empty window lit from within. And I am reminded of Karmitz talking about night. “Night is the relation to mystery, to death, to rebirth and life…what I look for in photography without knowing it, and often find, is that nocturnal presence”) Another I thought about but did not find was Portuguese photographer (and student of Frank’s work) Paulo Nozolino.

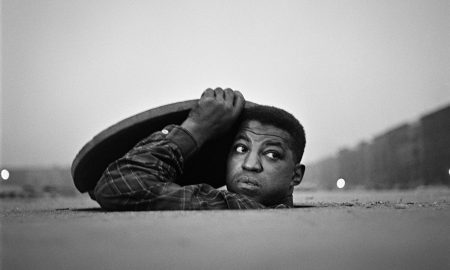

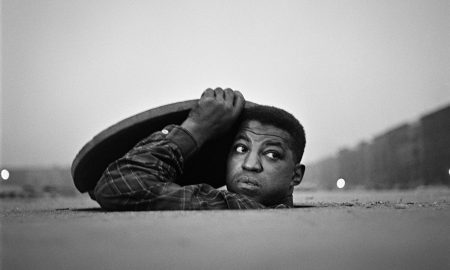

In the seventh and final room a dialogue is established between photojournalists and filmmaker Gordon Parks and James Karales. Parks I know well from his many Life magazine essays but I was far less familiar with Karales’s work a decade later for Look. Both often focused on the African-American struggle for civil rights, Parks as a creator of essays and films, Karales more as a recorder of the struggle as it evolved through the ’60s. The discourse is encapsulated by Park’s iconic image of a young African-American man’s head and arm emerging from under a manhole cover in a Harlem street (The Invisible Man, Harlem, New York,1952) and a Karales photo a decade later of a crying woman named Ellen. The notion of resistance connects to the Boltanski piece in the earlier section and also recalls the last thing Karmitz said in an interview I recently read, echoing well beyond the art world: “Resist to Exist”.

Gordon Parks’ The Invisible Man, Harlem New York, 1952 (courtesy the Gordon Parks Foundation)

The photo-essay is essentially a still form of a film, usually a newsreel. The French press predictably has jumped all over the exhibition as an equivalent of film: “a screenplay of multiple storylines”, a “silent production” and so forth, making the most of Karmitz’s cinema connection and leaning on the dominance of photography in Karmitz’s collection. Of course, the connection to the camera is significant – the power of the trace of actuality rather than the invention of the image. And there are the visible references in the dark corridors and faint spotlighting of the work installed, making each piece glow, activating our receptivity to the image as though audience facing a movie screen, plus the feeling of the layout suggesting something like mini film studios and set building. Additionally these superficial (in a non-perjorative sense) relationships are echoed in deeper understandings, relatable to direction and scriptwriting, and even dialogue in how the work is asked to converse among itself.

But Karmitz’s makes clear that his reverence to the single image (and sometimes grouped images) and appreciation of photography is profound, as a medium which of itself can propose multiple meanings and stories; “a thousand films in a single image” is how he puts it (dispelling/inverting the idea of as many words in a single picture). Photography, after all, is embraced by the French as a French medium (along with cinema), its invention at the hands of the Frenchmen Nicéophore Niépce and Louis Daguerre (notwithstanding the British contributions), with reportage photography, rooted as it is in the real, very much alive and well in France. The original idea of documentary photography was a subjective, dramatic mode of expression containing real people and real situations, an idea to which Karmitz seems to have connected.

Someone (perhaps from mr) has bestowed titles to several groupings through the exhibition: the initial corridor is called “A voice for those who have no voice”; the section which begins and end with Schuh is called “Contradictions of history”; the central corridor we have just traveled is “Taking a stance.” I have been hesitant to reveal them as they don’t feel to me as though Karmitz would have fastened them to the exhibition, which I believe he wants to contain undirected meaning, for each viewer to derive for her/himself.

Karmitz told one French interviewer “What touches me in a photo is linked to my own history, the history of a part of the 20th century,” locating the Barthesian punctum of each as much inside himself as in the image; it’s his own history the art references, so not all the art is made in the latter half of the 1900s (although most is).

The succeeding section in mr’s small guide is called “The shadow of Beckett” and juxtaposes works of similar subject matter, from different eras. I won’t attempt to cover them all, but the initial groupings address children and families. Then an entire wall engages eyes, from Eikoh Hosoe’s portrait of Japanese actor Yukio Mishima from his 1963 opus Barakei (Ordeal/Killed by Roses), to the great British photographer Bill Brandt’s large close-up of sculptor Louise Nevelson’s eye, a “post-surrealist” self-portrait by the Portuguese photographer Jorge Molder and Andy Warhol’s three-piece painting Eyes Looking Right. Other body bits include Christian Boltansky’s Prague Hands; two nearly full body-sized black and white photographs of isolated Ears by Annette Messager, then painted on directly, resembling tattoos, but also drawing on the tangential arts of palmistry, chiromany, children’s book illustrations and medieval manuscript illustration (from her series My Trophies 1986-88); and Gérard Fromanger’s absent body part but self-descriptive Electrocardiogram-Painting, Ivory Black from his series of such enlarged ECG printouts, The Heart Does What It Wants (2013). Another grouping looks at the body in motion and corrals Richard Avedon, Constantin Brancusi, Alexey Brodovitch, Man Ray and the Czech photographer Joseph Sudek.

For this section exhibition guide waxes interpretive. “The body falls apart, its constituent elements coming under sometimes sensual, sometimes savage scrutiny. Such fragmentation introduces the absurd into this contemporary theatre, haunted by the ghost of Samuel Beckett… One can’t help but think of how the body is treated in Beckett’s work… “ It may be my failing that it was not foremost in my thoughts. Beckett and Karmitz, it tells me, were often collaborators and drinking companions. In yet another room of the exhibition a film adaptation of Beckett’s play Play (1963) is screened.

The second to last section as titled in the program “Artists in history”, begins with one of the German Neo-Expressionists Gerog Baselitz “upside down” paintings from the 1970s. By this time I’m almost running through the exhibition, partly because it so fills me with energy and partly because I’ve spent so much time in it that our bus will soon leave. Appropriately I am pushed or chased by a looming Praying Mantis (1946) by French sculptor Germaine Richier and a 20-second, tortuous Hostage Head by Jean Fautrier, from his Hostages series of faceless heads and torsos evoking torture victims made while in a mental asylum during WWII.

After a visual dialogue between drawings by the Polish dramatist Stanislaw Ignacy Witkiewicz who committed suicide in 1939 and theater director Tadeusz Kantor, founder of Krakow’s Independent Theatre during the Occupation, who staged his plays in the 1950s, I turn to face a brand new installation/film by Christian Boltanski, White Animitas (2017): a very large, very white, seemingly endless space drawing the viewer into a featureless landscape inhabited only by black stem-like poles, each with a single bell dangling. The tile references roadside shrines erected by Latin American Indians to honor their dead, and Boltanski comments it’s “the music of the stars and the voices of floating souls.”

Nearby is the Swiss artist’s Louis Soutter’s haunting, terror-filled painting Before the Massacre, pushing me on. Turning once more, in a sunken space, I enter a vast installation, The Ghosts of Seamstresses (2014-15) by Boltanski’s equally renowned wife, the artist Anette Messager, featuring black, stuffed suspended pins, needles and scissors.

front: Louis Soutter, Avant le massacre, 1939 © Louis Soutter, Courtesy Collection Marin Karmitz, Paris;

back: Anette Messager, Les Spectres des couturières (The Ghosts of Seamstresses) 2014-15 © Annette Messager, Adagp, 2017, Courtesy Marian Goodman Gallery

Also in the darkened basement gallery is a video installation by the later Iranian filmmaker Abbas Kiarostami, Sleepers (2001) allowing a sleeping couple to sleep as dawn and street noise threatens to intrude and awaken them. Renaissance man Chris Marker, best known for his film essays and films, contributes photographs merging portraits of women with the faces of First World War veterans.

The exhibition proper ends (there are two more pieces in the cafe) with a single black and white photograph from Hiroshi Sugimoto’s portraits of cinemas, exposed only by the illumination from the screen during the entire run of a film, the result of which makes the screen glow piercingly white. The invisible film in this photograph is Michael Haneke’s 2001 psychological drama La Pianiste (The Piano Teacher) and the cinema is the mk2 Bibliotheque (Library) cinema. Seen from behind, the actor Isabelle Hupert views this blank screen, which when viewed over normal time, contains perhaps her most iconic performance. This is its own psychological drama encapsulated as a photograph, subverting Karmitz’s love of the instance of a photograph while still having the semblance of an instant, with the framed image within – where the movie should be – erased by allowing approximately 150,000 photographs, each one a frame of the film, to glide by Sugimoto’s camera until they erase all trace of themselves, Hupert and the film. I imagine a grim laugh from Karmitz every time he looks at it.

Karmitz is in awe of photography, and what a single photograph can do in an instant, which for him is unparalleled in art, “when you need so many to get things across with a film.”

In writing about this exhibition, many critics have seized on its physical and emotional darkness, which is there to be sure, and of course overt and covert connections to cinema. But I think what is more interesting is a quality nearly all of the pieces have, which seems almost a non-identifiabity – not only despite but because of the specificity of their medium (I am speaking here primarily of the photographs) – works which elicit mystery and provoke the viewer to find their own readings, work Karmitz calls “open.” He says “I have always liked open works, works that don’t impose a vision of the world but, on the contrary, open onto a vision of the world, a proposition… Open works secrete incredible mysteries… in contrast, [I have a] loathing of all those works that underscore all their intentions and play us for fools.”

So this collection is closer to what the Italian novelist and poet Erri de Luca calls “a museum of a man.” It’s a joy to move among the works gathered by this man and exhibited in this space, a man with a filmmaker’s eye whose regard for photography is so strong it’s almost a reverence. Karmitz here proclaims each photograph as a creation in its own right, placed unquestioningly among paintings, drawings, sculpture and film he loves, and then yields it dominance. Karmitz’s appreciation glows from these walls.

La mason rouge deserves enormous credit for the exhibition, clearly a collaborator with Karmitz. Tremendous thought and attention have been paid to revealing Karmitz’s relationship to the works, and the works’ to each other. Here is where the “bitter” part of the experience arrives, that enervating feeling I experienced just before having to leave the mr. Before the end of 2018 the mason rouge will cease to exist. La mason rouge is a private art center funded by a private foundation, the Fondation Antoine de Galbert, and Monsieur de Galbert has decided to close it in a desire to seek “a new direction for my foundation.” Such is the prerogative of private ownership, even of a space which has become so public and so much a part of the cultural landscape in its 14 years. “I am neither ill nor financial ruined” he told the newspaper Le Monde “Everything is fine… I just can’t see how we could do any better or go any further.” I guess people in Paris have known about this since its announcement earlier in the year and have got accustomed it, but it came as a profound shock to me, and, a month later and a continent away, I still feel myself in something akin to mourning for its impending loss. I suppose one must applaud and thank Monsieur de Galbert for his initiative in creating the mr, but right now I mostly feel disappointment. Two more exhibitions to go, then it’s gone.

–William Messer

a list of artists

Michael Ackerman, Dieter Appelt, Richard Avedon, Francois-Marie Banier, Georg Baselitz, Gao Bo, Christian Boltanski, Constantin Brancusi, Bill Brandt, Alexey Brodovitch, Vincenzo Camuccini, Geraldine Cario, Roy Decarava, Otto Dix, Jean Dubuffet, Bernard Dufour, Antoine D´Agata, Patrick Faigenbaum, Jean Fautrier, Fernell Franco, Robert Frank, Gisèle Freund, Gerard Fromanger, Alberto Giacometti, David Goldblatt, Julio Gonzalez, Beatriz Gonzalez, Sid Grossman, George Grosz, Vilhelm Hammershoi, Dave Heath, Lewis Hine, Ferdinand Hodler, Eiko Hosoe, Tadeusz Kantor, James Karales, Andre Kertesz, Johan van der Keuken, Abbas Kiarostami, Josef Koudelka, Sergio Larrain, Saul Leiter, Leon Levinstein, Vivian Maier, Stephane Mandelbaum, Juan Manuel Castro Pietro, Chris Marker, Annette Messager, Duane Michals, Joan Miró, Jorge Molder, Juan Munoz, Oscar Munoz, Jeremie Nassif, Panamarenko, Gordon Parks, Anders Petersen, Man Ray, Martial Raysse, Germaine Richier, Gerhard Richter, Maryan S. Maryan, Oskar Schlemmer, Gotthard Schuh, Louis Soutter, Nancy Spero, Christer Strömholm, Josef Sudek, Hiroshi Sugimoto, Alina Szapocznikow, Ulay, Moi Ver, Virxilio Vieitez, Roman Vishniac, Kara Walker, Andy Warhol, Stanislaw Ignacy Witkiewicz