Traversing the Art Academy of Cincinnati’s galleries via the looming, metallic stairwell, Covergys Gallery is perhaps the easiest to miss between the larger Pearlman and Childlaw Galleries. A sweeping horizontal pocket within a wall, the second floor gallery is at once invitational and necessarily participatory – it simply can not be ignored, as it effectively a continuation of the hallway corridor that it occupies. On display from February 9 to March 9, 2018 is a curious exhibition titled Fiction (with only daylight between us), an expansive group exhibition organized by painter Jeffrey Cortland Jones, in which each participant submitted an 8.5 x 11” black and white image. Each image was subsequently xeroxed and sent for exhibition, and the show has traversed an international semblance of gallery spaces over the last few years, with the Art Academy of Cincinnati’s Convergys Gallery as the final display. Fiction penetrates and fertilizes the gallery’s empty space, which is unframed by a border, door, or walkway. The beguiling immersive gallery is aptly appropriate for the current show, which facilitates virtual discourse between a multitude of international artists – curator Jeffrey Jones reached out to his “friends” on social media platforms such as Facebook with the intent to string connections with otherwise strangers. Jones explores the “endless design possibilities of the grid” (Muente, Tamera Lenz) in his painting oeuvre, and, similarly, his curatorial project Fiction implores virtual grids alongside their discursive metanarratives, traversing the psychologies and economic patterns of net-based dissemination.

As media theorist James Reveley evinces in “Understanding Social Media Use as Alienation: a review and critique,” social media networks such as Facebook facilitate opportunistic agential expressions relative to the digital era of capitalist production. Reveley borrows a post-Marxist language from Jean Baudrillard’s The Consumer Society: Myths and Structures, denoting that consumer society’s virtual emergence has ushered in an age of radical alienation, resulting in media consumption as an active, collective behavior enforced through institutions, group integration and social functions. Hence, social media platforms, brimming with content producers and aesthetic defalcators alike, foments a new mode of socialization related to the predominance of algorithmic productive forces and the monopoly of restructuring materialism, ushering cultural artifacts into immaterial virtual form. Socialization is a central pillar in the exhibition, allowing for the show to operate metaphorically and materially. The exhibition title reads Fiction (with only daylight between us), an exhibition and social experiment. Jeffrey Jones qualifies Fiction as a “social experiment,” using the show’s headline metaphor of the immaterial ephemera of “sunlight” as a connective binding agent between artists.

Hence, the circulation of immaterial media objects – photographs, memes, videos, and audio – often accompanied an “affect of alienation,” rendering the exploitive loss of creative authorship and reductive readings. Jones’ curatorial endeavor – which features 200 artists from 16 countries – undertakes a sizable project, where a multitude of visual and literary artists’ works are presented in amalgamate fashion. Jones states that “The project came about through a conversation with a friend about how many “friends” we have that we never interact with or who we don’t even really know on the various social media platforms, and how we tend to collect ‘friends’… So I wanted to change that, and know the people who came across my screen daily. This project has given me the opportunity to reach out to my Facebook ‘friends’ and start a true friendship and collaboration with them.” Consequently, consumer sovereignty and active participation – both in social media and in Jones’ “social experiment” – allot for Fiction’s sociological parlance. Much as Facebook users and social media participants specifically choose to share posts, images, and content to engage with other platform users, Jones explores the conscious participation in the virtual process of commodification re: personal information stripped from the user, manifest in these monochromatic renderings of artworks. Jones makes use of consenting participants in their own alienation while submitting the system to analysis.

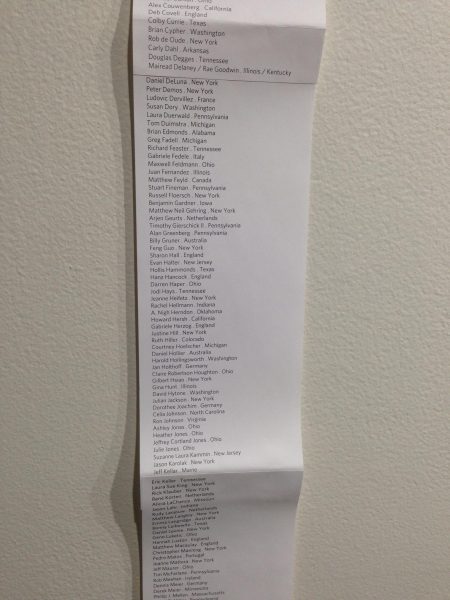

Fiction’s imagistic relay consists of homologous monochrome paper prints that sprawl across gallery walls, changing form with every showcase. For instance, Findlay, Ohio’s The Neon Heater Art Gallery presented the group exhibition in 2014 with segmented blocks of images trailing across a few walls, facilitating a reading that follows a narrative gaze. Convergys Gallery’s exhibition coordinator Matt Coors has opted to present Fiction as a large, unified mass, underscoring the economy of neo-liberal distantiation in virtual modes. At Convergys Gallery, a homogenous blockade of black-and-white xerox copies pair laconic poetry and photographic object studies beside one another. Despite the show consists of 200 hundred artists, the artists’ names are presented in list-form as the works, themselves, are devoid of subjective signifiers. Hence, the virtual affect of alienation is visually palpable, as the insurmountable and impossible task of connecting works with their authors invites textured associations, pairings, and interpretive readings.

Some of the show’s ambigious and surreal images of marred subjects, portraits, and case studies mirror the aesthetics of Outsider Art and Art Brut, where demonstrative elaborate fantasy worlds reverberate with diverse subconscious psychologies. The “outsider” artist is historically ascribed to children and mentally ill patients in Outsider Art’s cannon. Fiction’s “otherization” is a consequence of black-and-white uniformity, where thumb tacks buttress the paper prints, suggesting the cool estrangement of court-martialed evidence Infamously, Outsider Art championed interloper creatives such as Adolf Wolfli, a mental patient whose epic geometric drawings were documented in 1921 by Dr. Walter Morgenthaler in his book in Geisteskranker als Künstler (A Psychiatric Patient as Artist). Similarly, etched contorted geometric figures accompany abstract monochrome color field photographs while representative figures – a standout being a cartoonishly printed flamboyant court jester – invite the Fiction audience to meditatively consider each work through autonomous and collective lenses. There are brazenly detailed works, a favorite of which presents the object study of a fetid, moldering soccer ball, rotting in its core like a discarded apple. A parallel to social media’s schizo-social relay of alienation, the works are absent of any signature or index of authorship and are reduced to ubiquitous black-and-white renderings. Hence, this invites a more collective question – particularly pronounced when considering Coors’ decision to marry the works in a uniform figure. The collective works’ variable harmony promotes pattern recognitions, as the soccer ball photograph is closely tied to an etched representation of the planet Earth, which occludes a reproduced action painting and hexagonal mesh of shapes.

Unfortunately, the exhibition is patently indiscriminate, which results in instances of sophomoric admission, Fiction’s most detracting feature. One poem’s concise description of a chance sexual encounter resounds of hipster “indie poetry” and lacks substance when autonomously considered. Nonetheless, the indiscriminate engagement here – albeit, idle and threadbare at times – is a necessary and unique function of Jones’ social experiment of a project.

Having reached out to an assembly of extraneous artist friends, Jones’ decision to present each work in conjunction invites questions of immaterial labor, and the social factory lens, where the virtual sphere’s system of “value-creation” depends on the success of dissemination. Often times, platforms such as Facebook, Tumblr, and Instagram’s most widely dispersed visual culture artifacts are those prone to algorithmic prowess and “shareability,” hence allotting for buzzfeed quips in meme form to comrpise “trending” pages alongside faceless artworks (authored by an artist now estranged and removed). Such is the net-networked form of subjectivity, which functions to reproduce capitalism’s social relations where systematic estrangement and value extraction operate in parallel to social clout (Pybus, Jennifer) – the Instagram user’s athletic, fixed thumb refreshing an infinite feed, as “likes” and “shares” amass.

Consequently, Jones’ decision to ubiquitously invite Fiction’s contributors into an omnipresent aggregate, coupled with Coors’ conglomerate corpus, facilitates a rather interesting function. Fiction’s operating fulcrum is that of a framing device – borrowing the language of institutional critique from new media bastions like Brad Troemel and Artie Vierkant in framing the internet’s tendency to forward visual culture’s objects into immaterial haptic discourse. Every artist’s work, estranged and stripped of their subjective economy, convoys the contributors to participate in the alienation affect of social media while drawing distinct attention to social media’s mystified economic processes. Fiction’s extant works mirror social media engagement, where users bolster metadata collection and algorithmic development, facilitating the virtual affect of alienation. Fittingly, an aptly quizzical, inviting silkscreen portrait of a man with a raised eyebrow is subtitled with the text “have you seen me?” Fiction’s response denotes the impossibility of justly answering this inquiry and the ushers metaphorical readings to rectify the varied quality of the works when individually considered.

–Ekin Erkan

Works Cited

Baudrillard, Jean, et al. The Consumer Society: Myths and Structures. Sage, 2017.

Muente, Tamera Lenz. “Jeffrey Cortland Jones.” CityBeat Cincinnati, 20 Aug. 2008, www.citybeat.com/home/article/13019110/jeffrey-cortland-jones.

Pybus, Jennifer, et al. “Hacking the Social Life of Big Data.” Big Data & Society, vol. 2, no. 2, 2015, p. 205395171561664., doi:10.1177/2053951715616649.

Reveley, James. “Understanding Social Media Use as Alienation: a Review and Critique.” E-Learning and Digital Media, vol. 10, no. 1, 1 Feb. 2013, pp. 83–94. Sagepub, doi:10.2304/elea.2013.10.1.83.