“The face is a living presence; it is expression… The face speaks,” writes the French philosopher Emmanuel Levinas in his book Totality and Infinity. The face speaks of the “other” that it represents, to the “encounterer” who meets it, but also to the artist who depicts it in his/her portraiture artwork and to the viewer who is exposed to it. It speaks of the human subject, but also in the case of an art piece, of the creator artist, of the times it reflects, of the psychological, socioeconomic and political conditions that gave it birth. The face, and in particular in art the portrait that shows it, tells a story, the story of humanity, of its progression, of its successes and happy moments, but also and not rarely, of its upheavals.

I just returned from a trip to Lebanon where I had the chance to see the beautiful show “Face Value: Portraiture (A Gallerist’s Personal Collection)” at the newly and handsomely designed Saleh Barakat Gallery in Beirut. The show consisted of 100 portraits that the gallery owner and patron of the arts, Saleh Barakat, had collected over the years. It included works that spanned the early twentieth century up to our present day, all reflecting the exquisite sensibility of the owner gallerist, and making multiple statements about the subject, the artist, the times, and the evolution of this particular type of art. Works were in various media, including drawing, painting, print, sculpture, photography, mixed media, all by Lebanese and Arab artists.

Starting by an idealized representation of notable bourgeois individuals at the beginning of the century, the works included progressed to depict friends and family, loved ones, self- portraits, political figures, portraits that made political statements, and others depicting social conditions, representing the oppressed, the marginalized, the discriminated against. They also showed a progression not only in the themes addressed but as well in the representational techniques utilized. They moved from the classical academic execution of the early century, focusing on the literal realistic representation of a person, to a freer approach, exploring new ways of addressing the symbolic aspect of the subject, going beyond his/her physical appearance, depicting the sitter’s character, her/ his inner feelings and emotions. This was achieved by different uses of composition, of color, giving in many instances additional importance to the background as a reflection of both the psychological and other attributes of the subject as well as those of the artist.

In his two oil portrait paintings dating circa 1900, Lebanese painter Habib Srour (1860-1938) represents with an exquisite technique a woman and a man each occupying most of the canvas. Using a muted and neutral background, Srour focuses on their illuminated faces which shows stern and determined looks, depicting their social authority; he underlines, at the same time, by their dark, yet elegant cloth, their bourgeois belonging. In another painting from 1910, Srour represents the portrait of a poor bedouin woman. He uses softer colors throughout the canvas, depicting a less severe and somewhat resigned hagard gaze of the sitter, thus alluding to her lesser social class and personal circumstances.

Many self- portraits were included in the show, earlier ones classical in their approach and content, others and later ones more modern in their concept.

Sacha Abou Khalil’s (Lebanon, b 1964) “Notes from Underground, by Dostoievski 1864”, painted in 2017, represents him as the isolated and somewhat lost actor of that existential story by the renowned Russian novelist. The sitter is seated at a table, his feet bare, looking straight ahead as if asking what to write in the open notebook laid in front of him. Behind him life seems to be passing in the form of indistinct dark silhouettes, only one of them well outlined, that of a naked female with the same red color as his vest. Is she his only pressing connection to life? Abou Khalil’s self-portrait is less about how he looks but more about who he is, what he feels, how he connects as an individual to life.

Huguette Caland’s (Lebanon, b 1931) earlier 1972 pastel drawing, daring by its content for the time, represents her face split in half by what can be a reference to female genitalia. It thus affirms her femininity, her sexuality, and therefore, that important facet of her being, the specifics of her gender.

In addition to portraits of political figures like the 2007 painting by Rima Amyuni (Lebanon b 1954), representing the faces of 3 politicians as seen in posters pasted in the streets of Beirut, many portraits made political statements about issues of the times or of reflections of the artist’s views.

Ayman Baalbaki’s (Lebanon, b 1975) fifteen acrylic paintings done between 2011 and 2018 and displayed side by side as a single piece, hide the human face of the subjects either behind a ski mask, or a gas mask, or safety goggles… Baalbaki is seemingly alluding to the disappearance of the face of humanity and to its replacement by protective and isolating gadgets, confronting the barbarity of current life, necessitating continuous struggles, hiding, and the oblivion of what is human.

In his 2014 ink and acrylic (mixed media) drawing, Houmam Sayed’s (Syria, b 1981) portrait is that of a dead mummified individual wrapped in a typical national ethnic cloth. It is his painful comment on the face of Syria devastated then by an emerging civil war, a war effacing the humanity and the history of his country.

Salah Saouli (Lenabon b 1962) on the other hand, calls attention, in his 1992-1994 mixed media portraits, to the unknown fate of the disappeared of the Lebanese civil war. His installation, realized a couple of years after the end of that war (1990), sheds light on the situation of the disappeared and brings them back to life. He uses light to highlight their outlined faces which seem to beg the viewer to notice them and not to forget their destiny.

Addressing the Iraq war, Serwan Baran (Iraq, b 1968), in “The Last General”, his 2015 acrylic painting, depicts a heavily decorated general, dressed in his military uniform, leaning on crutches and with an indistinct, almost effaced, disappearing face. He stands in a desolate background, one devoid of structures and with no clear reference, adding to the feeling of instability, collapse and impermanence.

Artists also used their own version of portraits to make comments regarding their personal political beliefs.

Seta Manoukian (Lebanon, b 1945) and Omar Fakhoury (Lebanon, b 1979), both use their portrait paintings to convey their views of our capitalistic and for profit society. In her 1989 “Untitled” acrylic painting, Manoukian represents, in the lower half of the canvas, a horizontal recumbent well- suited businessman holding his leather attache case, and above him, two ceremonial empty, unstable and falling chairs. It is obviously her negative comment on the futile and collapsing business world in which we live.

Fakhoury uses the same idea in his oil painting “Building with Tie” completed more recently in 2018. The large upper half-faced portrait of a corporate man with a tie, either a businessman or a politician, is roped to the empty shell of an unfinished cement building. The association and juxtaposition of both elements speak of the current deteriorating reality in the country and of the devastating one to be expected, of the empty promises and half truths corporations, businesses and politicians give.

Artists also used portraits to address certain social realities they live and to make comments about socially important and timely issues.

In their portrait paintings both Rima Amyuni (Lebanon b 1954) and Tagreed Darghouth (Lebanon, b 1979) give voice to their foreign domestic helpers, adding a gentle attention to these individuals who are many in Lebanon and not always treated well. Amyuni’s 2014 oil painting “Dani and Sunflowers”, represents tenderly Dani, her Sri Lankan helper, sitting restfully in front of a colorful vase of flowers. And Darghouth’s 2010 acrylic painting surrounds the central image of her helper cook with various cooking elements, important to her daily life.

Serwan Baran (Iraq, b 1968), on the other hand, gives the stage to a Down syndrome trisomic person he knows. He depicts him beautifully and tenderly in his 2017 acrylic painting “I am a Number Like You”. He elevates him to the level of any other worthy individual, stressing through the use of numbers in the background, that we are indeed all the same, just numbers, in the big scheme of life.

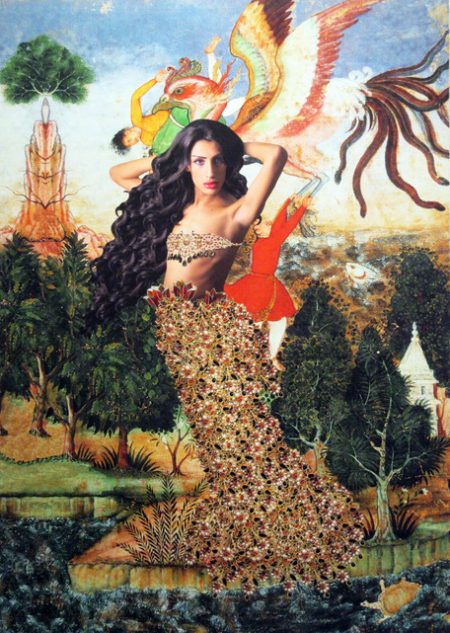

Chaza Charafeddine; “L’Ange Gardien II, from The Divine Comedy series”, photomontage, digital print on canvas, 10x70cm, 2010

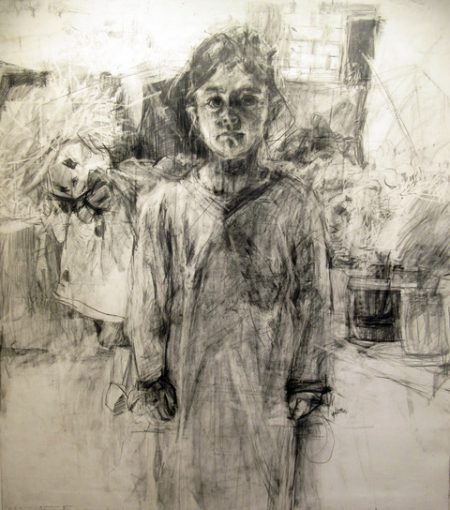

Using some appropriated art images Chaza Charafeddine (Lebanon b 1964), propels, in her 2010 photomontage digital print “L’ange Gardien II, from the Divine Comedy Series”, the image of a transgender individual as a hero and an angel. And in “Shahd”, her 2016 pencil drawing, Hala Ezzeddine (Lebanon, b1989) represents the portrait of a noble, yet, unfavored and sad child, most likely a refugee product of one of the many current wars in The Middle East.

Finally some of the portraits included were mere representation of psychological states that the artist wanted to address.

Nadia Safieddine’s (Lebanon, b 1973) 2017 oil painting “The Envious” uses heavy, thick, somewhat abstract strokes of paint to barely outline the shape and elements of the face of an individual difficult to recognize. It is as if envy, the topic that she is addressing, has consumed its subject.

And Farid Aouad (Lebanon, 1924-1982), in his 1965 oil painting, represents the silhouette of a man, with obscured facial features, almost floating in the background like a ghost, a furtive passerby in this somewhat fuzzy world.

There were many more beautiful and meaningful “portraits” included in the “Face Value: Portraiture” show. Suffice it to say that they all worked together to compose a cohesive body of work, one that enlightened the versatility and power of the portrait art genre to speak of humanity, of the subject, of the artist and of the evolving times. The panorama Saleh Barakat presented spoke in addition of the evolution of this genre, of the changes in its techniques over the years, and of the freedom artists have been taking increasingly to reinvent it and to incorporate themselves in addition to their subject in its content.

–Saad Ghosn