Fashion is a fickle lover, and it jilted Louis Comfort Tiffany at the end of his career in the 1930s. He had been the American exemplar of Art Nouveau, or “new art,” which emerged in Europe in the 1890s after a century of revivals. But “new” eventually grows old, and by 1910 its curvilinear and sinuous lines were getting straightened out by the rectilinear Bauhaus aesthetic and Art Deco style. The Machine Age had triumphed over nature.

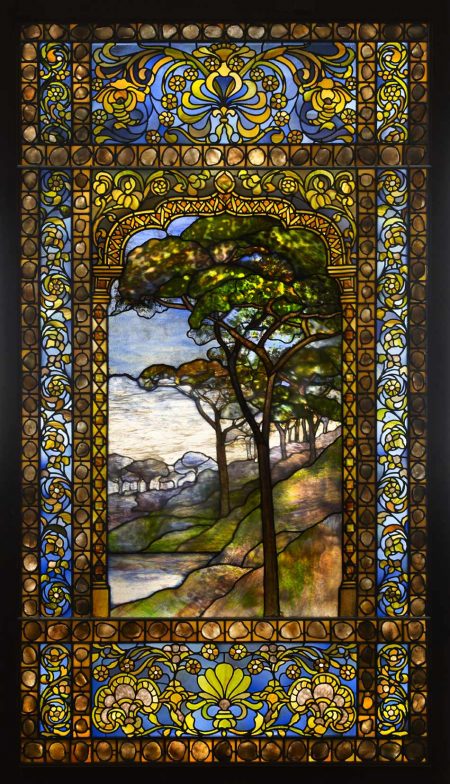

Tiffany Studios, “Garden Landscape Window”, 1900-1910, leaded glass. Photograph John Faier. © 2013 Driehaus Museum

Because of this shift in fashion, Tiffany’s work was consigned to museum storerooms and banished to the attics and garages of grandchildren not quite ready to let go of their grandmothers’ once prized treasures. (The Wisteria Lamp, 1901, made up of 2,000 pieces, originally cost $350 and went for $1.56 million in a December, 18, 2013, Sotheby auction.)

Scholars and collectors rekindled the public’s love affair with Tiffany in the 1950s. Thanks to two prominent collectors, Cincinnati has been treated to two splendiferous shows of Tiffany’s work in the past year. “Tiffany Glass: Painting with Color and Light,” shown at the Cincinnati Art Museum last spring, was drawn from The Neustadt Collection of Tiffany Glass in Queens. (See Karen S. Chambers, “Tiffany Glass: Painting with Color and Light,” aeqai.com, April 2017.) The collection was assembled by Dr. Egon and Hildegard Neustadt, who purchased their first piece of Tiffany in 1935: a lamp found in a Greenwich Village second-hand shop.

The Taft Art Museum is presenting “Louis Comfort Tiffany: Treasures from the Driehaus Collection” from the Richard H. Driehaus Museum in Chicago. Over the course of the last 35 years, the financier and philanthropist has acquired more than 1,500 Tiffany works, including vases, lamps, windows, furniture, and ornamental works. In 2008, he opened the Richard H. Driehaus Museum in a Gilded Age mansion to house this collection as well as one of the preeminent collections of American and European decorative arts.

Son of the founder of Tiffany & Co., Charles Lewis Tiffany1, the younger Tiffany did not join the family business until 1902, the year his father died and he became Tiffany & Co.’s first design director.

Tiffany Studios, “Landscape Window”, 1893-1920, leaded glass, quartz stones. Photograph John Faier. © 2013 Driehaus Museum

Tiffany’s first love was painting, and he studied with a number of the leading artists of the day, including George Inness, Samuel Colman, Léon-Adolphe-August Belly, and at the National Academy of Design in New York City in the 1860s. He also studied in Paris from 1868 to 1869. This training would particularly inform his designs of leaded glass as he sought to emulate oil’s nuance of color in the medium of glass. He helped to develop techniques and unusual glasses to achieve those effects.

Like many men of wealth, Tiffany made the Grand Tour to Europe and continued on to North Africa, and returned often from the 1860s through 1871. The decorative arts, or as the French call them objets de vertu, he had seen on his travels determined the artistic focus of his career.

Tiffany Studios, “Water Lily Millefiore Vase with Stand”, about 1910, blown glass, gilt bronze stand. Photography by John Faier. © Driehaus Museum

Tiffany’s distinctive look was informed by The English Aesthetic Movement, which began in the 1860s, and the international Arts and Crafts Movement born in the 1880s. Both movements valued the handmade over the machine-made and extolled beauty over strict functionality.

Tiffany Studios, “Snowball Hydrangea Floor Lamp”, about 1903-1910, leaded glass, bronze. Photograph John Faier. © 2013 Driehaus Museum

But to my eye, what most inspired his aesthetic vision was Art Nouveau, which he encountered at the 1889 Paris Exposition. He was particularly taken by Émile Gallé’s glass, a medium that appealed to Tiffany who had established Tiffany Glass Studios in 1885.

Tiffany had a natural affinity for Art Nouveau. He was enamored with nature and was inspired by flowers, birds, and insects, as was Gallé. Believing “Nature is always beautiful,” Tiffany often sketched outdoors. In the large gardens at his home on Long Island, Laurelton Hall, he grew many flowering plants, including peonies, wisteria (Wisteria Table Lamp, about 1901, leaded glass, bronze), daffodils (Daffodil Lamp, between 1899 and 1910, leaded glass, bronze), and hydrangeas (Hydrangea Table Lamp, about 1905-1920, leaded glass, bronze and Snowball Hydrangea Floor Lamp, about 1903-1910, leaded glass, bronze).

As his friend and art dealer Siegfried Bing, who popularized Tiffany’s work in Europe, commented, “Never, perhaps, has any man carried to greater perfection the art of faithfully rendering Nature in her most seductive aspects.”

Tiffany Studios, “Jack-in-the Pulpit Vase”, 1907-1910, blown glass. Photograph by John Faier. © 2013 Driehaus Museum

The Art Nouveau impulse may have been best expressed in Tiffany’s signature floriform vases with their slender “stems” that burst into extravagant blooms, obviating the need for actual flowers. The decorative clearly trumps functionality in these pieces.

Although Tiffany’s glasswork gets the most attention, his successive companies 2 produced a full range of decorative objects and even designed interiors, including rooms at the White House. 3

The exhibition presents some stunning examples of his non-glass decorative work. The gilt brass 1891 Altar Cross, bejeweled with topaz and amethyst, is stunning and is likely to have been inspired by medieval crosses he’d seen in Europe.

Tiffany Studios, “Covered Box”, about 1905, silver and transparent enamel. Photograph by John Faier. © 2013 Driehaus Museum

Less showy is a silver octagonal Covered Box, about 1905. The perimeter of the lid is accented with a row of luminous enameled circles that suggest emeralds. A line of strictly geometric oblongs march along the edge and morph into freer dots that bubble up. This arrangement is repeated on the sides. One can easily imagine it sitting on the dressing table of the wife of a robber baron.

Early in Tiffany’s career he was involved with fabricating the objects that came out his workshops, but he came to rely on artisans to execute his designs as demand increased. Tiffany’s studio system was not a simple enterprise; “he needed specialized employees — a hierarchy of artists and artisans—to accomplish his goals.”4.

Tiffany’s signature lamps were produced by “Tiffany’s girls,” the nickname for the Women’s Glass Cutting Department, which was established in 1892 with six women and headed by Clara Wolcott Driscoll. By 1897 Tiffany employed between 40 and 50 single women in this department (married women were not allowed to work.) He believed that “women were better suited than men for small hand work and possessed ‘natural decorative taste’ and ‘perception of color.’”5 The Tiffany girls had a free hand in the selection and cut the myriad pieces that made up the shade.

It was assumed that Tiffany was responsible for all of the designs coming out of the various Tiffany companies, but this was not the case. Driscoll, who Tiffany held in high regard,6 designed some of the most iconic Tiffany lamps. She was responsible for the Dragonfly Lamp, which won a Bronze Medal at the 1900 Exposition Universelle in Paris as well as the Cobweb, Butterfly, Poppy, Laburnum, Arrowhead, Geranium, and Wisteria lamps.7

Martin Eidelberg, professor emeritus of art history at Rutgers University, was instrumental in the acknowledgment of Driscoll’s contributions, which included designing moderately priced desk and boudoir accessories. He believed “Tiffany would have died’ if word had gotten out that Driscoll designed some of his most famous lamps.”8

Tiffany Studios, “October Night Table Lamp”, about 1910, leaded glass and patinated bronze. Photograph by John Faier. © 2013 Driehaus Museum

It’s worth noting that Tiffany required this department to be profitable, unlike others, so in addition to designing and overseeing the department, Driscoll also needed to have a sharp pencil.

Tiffany Glass & Decorating Company, “Eighteen-Light Lily Table Lamp”, prior to 1902, bronze, blown glass. Photograph by John Faier. © 2013 Driehaus Museum

The Eighteen-Light Lily Table Lamp’s glass shades drooped like actual trumpet flowers. This was only possible because the lamp was electrified, a major change suggested by Driscoll. This also allowed greater flexibility in designing the stand and base since they no longer needed to hold oil. The lamp was commercially successful, and customers could order the number of blooms and the base they desired.

A Tiffany trademark is the iridescent glass he called Favrile, which connoted handmade9. It was eventually applied to all of Tiffany’s glass as well as pottery and metalwork.

Favrile glass was inspired by the iridescence of the Roman and Syrian glass Tiffany saw at the Victoria and Albert Museum, London, in 1865. He described Favrile as having “brilliant or deeply toned colors, usually iridescent like the wings of certain American butterflies, the necks of pigeons, and peacocks, the wing covers of various beetles.”10

The glass was patented in 1894, and although Tiffany is generally credited with creating it, it was actually developed by Arthur Nash, a British glassblower hired by Tiffany to oversee the Tiffany glassmaking shop, which was known by various names.11 According to an article on The Corning Museum of Glass website, he never shared the formula with anyone, including Tiffany.12

Tiffany Studios, “River of Life Window”, 1900-10, leaded glass. Photograph by John Faier. © 2013 Driehaus Museum

Tiffany was most directly involved in his leaded glass windows, especially those with landscape elements. Here he could transfer his color sense as a painter into glass, layering mottled,13 striated, and opalescent glass to achieve painterly effects. In the River of Life Window, 1900-10, he placed two of his favored flowers – magnolias and irises — in the foreground, framing an atmospheric landscape that extends into the far distance.

Installed next to the River of Life Window is the absolutely captivating Seascape Window, made between about 1895-1902. Came (strips of metal that hold the glass pieces together) define the masts of a boat and outline the turbulent waves. It’s a masterful use of line, turning a technical requirement into an artistic statement. Tiffany layers different colors and patterns of glass sheets to create the raging thunderstorm. It is a tour-de-force and was displayed for a number of years in the Tiffany showroom at 333 Fourth Avenue in New York.

As they say, “everything old is new again.” Maybe Tiffany’s celebration of nature can be a message for those concerned with the fate of the planet.

–Karen S. Chambers

Taft Museum of Art, 316 Pike St., Cincinnati, OH 45202, 513-684-4516, taftmuseum.org. Wed.-Fri. 11 am-4 pm, Sat.-Sun. 11 am-5 pm. Admission: members free; adult $10 in advance, $12 at door; senior (65+)/youth (6-18) $8 in advance, $10 at door; children (5 and younger) free. Sun. free. Through January 21, 2018.

End Notes

1 Charles Lewis Tiffany and John B. Young opened a “stationery and fancy goods emporium” in Brooklyn, Connecticut. In 1837, it moved to Lower Manhattan as Tiffany and Ellis. The name was shortened to Tiffany & Co. in 1853 when Tiffany took control and established the firm’s emphasis on jewelry. “Tiffany & Co.,” “Tiffany & Co. For The Press | About Tiffany & Co. | Tiffany & Co. History | United States”. Press.tiffany.com. Retrieved 2015-08-01. Wikipedia.

2 “Although Louis Comfort Tiffany’s company is best known by the name of Tiffany Studios, established in 1902 and continuing until it filed bankruptcy in 1932, his vast creative enterprise operated under various names throughout the years: Louis C. Tiffany & Company, aka Louis Comfort Tiffany and Associated Artists, 1878-85; Tiffany Glass Company, 1885-1892; Tiffany Glass and Decorating Company, 1892-1900; Allied Arts, 1900-1902; Tiffany Studios, 1902-1932. Companies lending production support were Stourbridge Glass Company (after the center of British glassmaking), 1893-1902; Tiffany Furnaces, Inc., 1902-1919; and Louis C. Tiffany Furnaces, Inc., 1920-1928. Morsemuseum.org/louis-comfort-tiffany/tiffany-studios.

3 In 1882 Louis Comfort Tiffany, Associated Artists, decorated several rooms in the White House; unfortunately they no longer exist. “At that time we decorated the Blue Room, the East Room, the Red Room and the Hall between the Red and East Rooms, together with the glass screen contained therein. The Blue Room, or Robin’s Egg Room — as it is sometimes called — was decorated in robin’s egg blue for the main color, with ornaments in a hand-pressed paper, touched out in ivory, gradually deepening as the ceiling was approached.

In the East Room, we only did the ceiling, which was done in silver, with a design in various tones of ivory.” Quote by Louis Comfort Tiffany in Sarah E. Mitchell, “Louis Comfort Tiffany’s Work on the White House,” vintagedesigns.com.

4 “Secrets of Tiffany Glassmaking,” www.morsemuseum.org/on-exhibit/secrets-of-tiffany-glassmaking.

5 “Tiffany Studios Designers,” morsemuseum.org/Louis-comfort-tiffany-studios-designers.

6 Driscoll was highly regarded by Tiffany who gave her much artistic freedom, inviting her to Laurelton Hall, and including her on a three-month tour to Europe with other designers to sketch and photograph. Mark Bassett, “Breaking Tiffany’s Glass Ceiling: Clara Wolcott Driscoll (1861-1944),” www.cia.edu/news/sories/breaking-tiffany’s-glass-ceiling-clara-wolcott-driscoll-1861-1944.

8 Jeffrey Kastner, “Out of Tiffany’s Shadow, a Woman of Light,” The New York Times, February 25, 2007.

9 There are two theories about the origin of the name Favrile. It is most generally understood that it was derived from the Latin fabrilis meaning handmade. An alternative theory is that it comes from an Old English word for hand-wrought or handcrafted. William Warmus in his 2001 book, Louis Comfort Tiffany contends that Tiffany changed the name to Favrile because it sounded better.

10 “Tiffany glass,” en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Tiffany_glass.

11 The Tiffany Glass and Decorating Company, founded in 1892 produced glass, windows, and interior decorations, was renamed The Stourbridge Glass Company in 1893, Tiffany Furnaces in 1902, and Louis C. Tiffany Furnaces, Inc. in 1920. Arthur John Nash & Leslie Hayden Nash (Relating to Tiffany Studios) Archive, 1893-1957. The Juliette K. and Leonard S. Rakow Research Library, The Corning Museum of Art.

12 “TIFFANY TREASURES: FAVRILE GLASS FROM SPECIAL COLLECTIONS,” Jane Shadel Spillman. cmog.org.

13 “Ring mottle glass refers to sheet glass with a pronounced mottle created by localized, heat-treat opacifications and crystal growth dynamics. Tiffany invented ring mottle glass in the early 20th century. Tiffany’s distinctive style exploited glass containing a variety of motifs such as those found in ring mottle glass…” “Tiffany glass,” Wikipedia.