Gallery exhibits often feature artists at a specific stage of their career, a period marked by consistent subjects or stylistic choices. Some shows take a more contrastive approach, capturing the creative process at distinct moments and inviting audiences to consider the evolution of perspective, tonality, and preferred media. Less common, however, are shows that feature multiple artists adapting their practices to changes in their own bodies over a lifetime. The summer show at the Philip M. Meyers, Jr. Memorial Gallery at the University of Cincinnati affords precisely such historical portraiture, investigating performative convergences among eight different artists while also insisting on their specificity. The Persistence of Vision: An Exhibition of Early and Late Work by Artists with Macular Degeneration features a total of 50 pieces by people including Lennart Anderson, Serge Hollerbach, Dahlov Ipcar, David Levine, Robert Andrew Parker, Thomas Sgouros, Hedda Sterne, and William Thon. The show spotlights compositions from before and after the artists experience changes in their central visual perception. For some of the artists, the changes produce an almost total inability to see in the conventional sense. But as the exhibit’s title indicates, their vision remains, sometimes conveying its transformation through shifts in palette or resolution, and other times through the uptake of new genres and materials. For multiple contributors, the later works depend almost entirely on the interplay of imagination and muscle memory, with results that recall efforts from decades before, while establishing an aesthetic with its own focus and integrity.

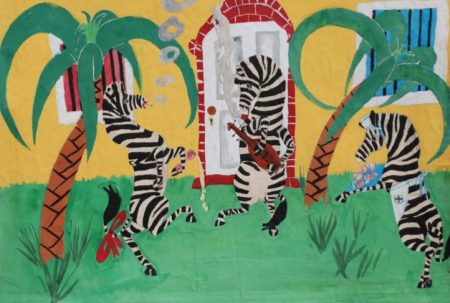

Such metamorphosis becomes especially clear in Dahlov Ipcar’s paintings of animals over three quarters of a century. Working as a children’s book illustrator while also producing tapestries, rugs, and collages, Ipcar produced a solo show at MoMA in 1939, making her the first woman and, at the time, the youngest artist to hold that honor. In Flapper Jungle, we see the whimsy of the illustrator converge with cultural commentary on the roaring ’20s, as she depicts zebras dancing, smoking, drinking, and playing instruments in a setting that evokes lavish spending and tropical wilds. Bold blasts of primary color coexist with bands of black and white as crescent shapes and loops move in rhythm across the visual expanse. Patterned striping links the animals to trees, window bars, and a brick doorframe. Although the flapper zebras augment the image’s sense of festivity, they also bring to the scene a certain reserve, a subdued and world-weary hedonism.

When macular degeneration set in, she retained much of her subject matter and style but found it difficult to render the finer details of her compositions. By her final years, the condition compelled her to work mainly from memory, relying on decades of rehearsed brushstrokes to craft fanciful new worlds. In an interview with curators A’Dora Phillips and Brian Schumacher, she stressed the delicacy of the process: “The hand knows a lot, but it can’t see through the fog” (21). We witness that delicacy in the unfinished Sunlight in Forest Glade, where the animals have become more translucent and fragmentary than in earlier paintings. But despite the changes in her perception, the scene overflows with intricacies. Diamonds of light pierce the jungle, producing a haze where a tiger and leopard seem barely to hold together while deer scatter in opposite directions. Boars and large insects populate the wooded expanse. A powerfully built puma spies the running deer. Symbiosis exists alongside predation; play and danger present themselves in equal measure. Vegetation and flowers provide scenic beauty and a degree of cover, though the penetrating light puts everything briefly on display. That shaft of sun, we may surmise, cuts against the fog that arrived late in Ipcar’s life.

Even as the fog thickened, Ipcar remained creative until after her hundredth birthday. The same is true for Hedda Sterne, who negotiated macular degeneration by relying on the memory of long-loved forms, and slowly shifting from painting to drawing. Like Ipcar, she had great success as a young artist, eliciting acclaim from Jean Arp for collages at a Parisian show in 1938. She worked in multiple media over the next half-century, experimenting with a range of subjects and genres. When vision began to dim in her eighties, she narrowed her focus to faces and natural objects. According to Lawrence Rinder, she drew with the support of a powerful magnifying glass, and “may have been unable actually to see the images [the late drawings] in their entirety. She probably only saw small sections of them, the highly magnified sections…but not the overall composition” (Phillips 28). The technology helped her attend to the small details, but Rinder hints that it was embodied memory, or the practiced feel of generating shape and texture, that primarily guided her hand.

As she neared her ninetieth year, she had not yet turned entirely to drawing, and was able to finish the mixed media piece In Memory of a Defunct Birch. The image evokes her identification with trees, which express the tension between the ambition to rise and the pull of gravity. The movement of branches upward and outward exists in graceful counterpoint to the slow drain into earth. A smattering of crystal against onyx boughs amplifies the energy of the piece, releasing fireworks at the core of the canvas. Given the grayscale character of Sterne’s surrounding works, splotches of mustard bring enhanced charge to the work, distinguishing it from its more restrained counterparts. The work’s title lends it an elegiac quality, designating not a birch in present bloom but rather the recollection of striving against the inevitable.

In the years after In Memory of a Defunct Birch, she began drawing figures she thought of as “ghosts,” or “faces from a remote past that appeared to her and wanted to be portrayed.” Untitled (January 17, 2002) contains one such ghost. At first encounter, the drawing presents a mass of wriggling strokes hovering in mist of varying density. Dwelling on the image, however, reveals things at once leafy and birdlike, along with one of the faces from Sterne’s personal history, resting on a hand bent at the wrist. The figure poses as if to attract the artist’s attention or playfully mimic the conventions of studio portraiture. With its slow self-revelation, the face connotes the longevity of remembered bodies long after they have moved on or become “defunct.”

Like Ipcar and Sterne, Lennart Anderson learned to rely on intuition as macular degeneration occurred, feeding the work forward without being able to count on holistic feedback from the canvas. The condition first affected his right eye, obliging him to rely mainly on his left. Six years later, the left eye underwent a transformation as well. Anderson’s Idyll series shows the changes over a forty-year period, with the third and fourth installments providing evidence of perceptual variation across the decades. He began the third entry in the 1970s, continuing to supply new details until shortly before his death in 2015. The painting vibrates with motion, music, and dance, all of which comes together as an affirmation of life. The scene also depicts intergenerational embrace in varied ways—some understated, as with depictions of children partaking in dialogue and games with adults, and others grandly demonstrative, as when a man in the background raises an infant to the heavens. Rolling hills extend the narrative throughout the natural world. Anderson returned to similar concerns forty years later in Idyll 4, where the palette darkens and the characters become smoky and soft. Unfinished bodies float in space, trying to come fully into being. Wrestlers and dancers bleed into on another. A muscled figure still raises a child to the sky, though this time with an angelic onlooker placed deeper in the field of view. The white of her garment at the center of the image pulls the focus to the celebration of birth.

Although less dramatic than the transition from Idyll 3 to 4, Anderson’s still life paintings also manifest profound alterations over the six years from 2001 to 2007. Salami on a Red Plastic Dish (2001) boasts exacting detail and texture along with an emphatic tangibility. Electric colors and photorealist splashes of light permeate the image plane. Lion’s Mask (2007) retains the affect of thickness and the fine-grained surfaces of things, but the color scheme has darkened, as with Idyll 4, to shades of late autumn.

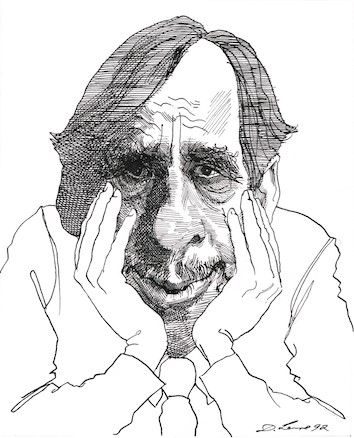

David Levine shared Anderson’s capacity to convey haptic experience through figurative painting, though he built his reputation on drawing caricatures of political and literary figures over nearly fifty years. The New York Review of Books ran those caricatures in every issue from 1963 to 2007, when editors stopped hiring him due to the effects of macular degeneration on his work. His 1992 depiction of Vaclav Havel finds Levine at the height of his powers, delineating subtleties of character with frank yet sympathetic pencil and ink. A former president of Czechoslovakia and the Czech Republic, Havel developed a reputation as a playwright who kept an eye on the dehumanizing effects of bureaucracy. Levine accentuates the political artist’s bemused expression, rendering the deep-set eyes with painstaking care, the etchings of compassion and worry on the forehead, the sweep of hair culminating in points on both sides. Heavy shading and wispy blurs emphasize the curve and shine of the facial features. The upper body discloses itself in the sparest terms, an uncomplicated support for the intricate countenance, accentuating its sophistication by contrast.

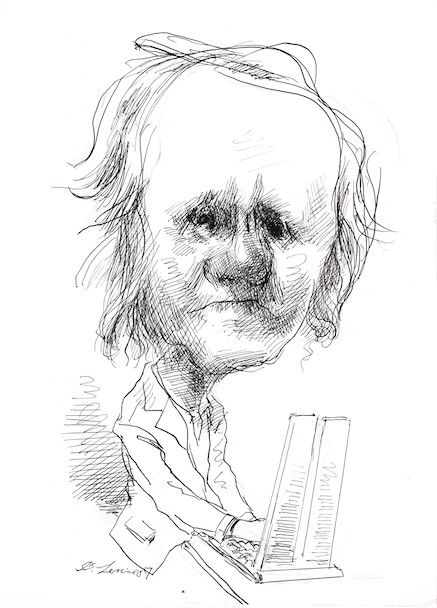

Fifteen years later, the thickness of detail has receded but the evocation of personality is, if anything, stronger. His 2007 caricature of Don DeLillo appeared the year he stopped receiving assignments, but it ranks among the more satisfying pieces in The Persistence of Vision. In novels such as White Noise, Underworld, and Zero K, DeLillo confronts the starkest of global problems—waste and pollution, nuclear proliferation, authoritarian politics, the commodification of everything—while cutting the tension with consummate wit. Levine’s portrait captures the contrast, juxtaposing the writer’s impish charm with a tightly drawn mouth and haunted eyes. The sketch makes DeLillo look older than his 71 years (at the time of the drawing), imparting an almost ancient quality to the face. But the effect is less cruel than heartwarming, a loving hint at the old soul that inhabits his prose.

Once the caricature assignments stopped coming, Levine gave his time to painting instead, spending some of the next year working on “The Last Battle.” Given the title of the piece, we might initially perceive silhouettes in the heat of struggle, arms flailing and punches landing as people double over with pain or exhaustion. But once we learn that bathers at Coney Island provided the inspiration for the image, the tone changes and the scene emanates joyful abandon. The battle takes place in the surf, with people splashing and squaring off on all fours. As with Anderson’s Idylls, adults and children take pleasure in each other and the physicality of place. A hymn to togetherness, the painting finds distinct identities to be less important than collectivity. As exuberant as is the sense of community, however, the scene also includes mysterious forms draped in towels or cloaks, forms that at first fit seamlessly into the oceanside tableau, but gradually infuse it with notes that are discordant and a little ominous. Those notes suggest a battle with mortality rather than just a romp among beachgoers.

Levine’s painting thus exemplifies the ambiguity that characterizes numerous works in the exhibit. Natural beauty brings danger, a beach outing doubles as combat, and ghosts hover amid celebrations. Sometimes the ghosts haunt the artists themselves, occupying an affective space between the comforts of memory and the dread of the otherworldly. While negotiating that space, the artists also confront the duality of everyday objects, inert or cast-off things that nevertheless hum with inner life. Doing so often means trusting an array of bodily sensations, and a lifetime of patterned movement, when optics no longer function in familiar ways. For some, adapting to the new situation involves shifting from painting to drawing or vice versa; for others, it entails taking up sculpture or multimedia design. On occasion, it means moving toward meditative forms of invention that resist expression through conventional means.

David Levine’s son Matthew captures the deviation from convention in a reflection on his father’s last years. After experiencing growing frustration with what appeared on the canvas, and revising his figures with charcoal again and again, the artist brought his work to what seemed an abrupt close. Yet one evening, when Matthew came to look after his father, he found him “slouched in the easy chair” before “The Last Battle.” When Matthew asked what he was doing, he answered,

“Painting.”

“You’re painting?” I said. No paints or brushes were out. And there was no smell of turpentine, which I’d associated with him all of my life.

“Yes,” he said. “I am imagining how I’d handle the sky.” (Phillips 23)

In such instances, the poignancy comes from knowing that vision persists in ways viewers cannot share. Then again, the prospect of giving perceptible shape to an idea is always uncertain. Distinctive as the show is, perhaps it only brings out the general problem of realizing those ideas, while drawing more than usual attention to creation as a precarious process, fully embodied and thus necessarily fragile.

–Christopher Carter

Works Cited

Phillips, A’Dora, and Brian Schumacher. The Persistence of Vision: Early and Late Works by Artists with Macular Degeneration. University of Cincinnati Library Publishing Services, 2018. get.html

August 27th, 2018at 12:45 pm(#)

“Thank you” to Christopher Carter for this insightful review. There is a minor error that gives me an opportunity to make a point. My father, David Levine, did not turn to painting only after his career as a caricaturist came to an end. He had been painting his entire life and, despite notoriety as a caricaturist, considered himself first and foremost a painter. His paintings, while derived from life, were entirely imaginative in their composition, coloration, selectivity and the exploration of the capacities of paint. He used to always say that “painting is play.” It was that attitude toward the making of art — and toward the living of life — that allowed him to retain his sense of self despite concessions to the aging process and the progression of his vision loss.