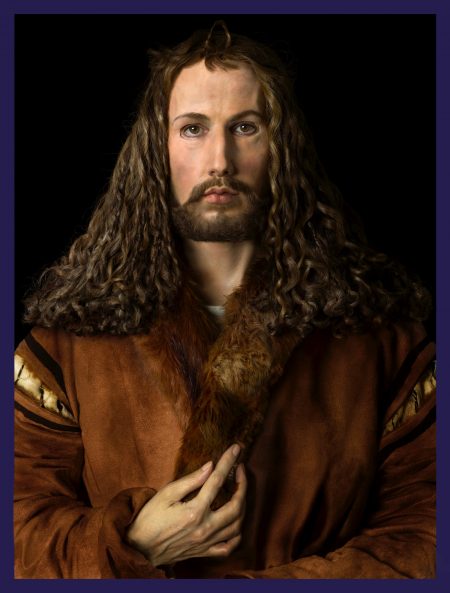

Gillian Wearing (b. 1963), Britain, Me as Dürer, 2018, chromogenic print. © Gillian Wearing. Courtesy of the artist, Tanya Bonakdar Gallery, New York / Los Angeles, Maureen Paley, London, and Regen Projects, Los Angeles.

Masks serve multiple metaphorical and social functions in the world. In ancient Rome, wax masks were cast directly from the faces of the dead, preserving the countenance beyond the life of the body. Ritual societies often employ masks spiritually, transforming the wearer into a being from the spirit world as part of a rite of passage or seasonal transition. Colloquially we think of identity as a mask, as a means of producing an interface between our private selves and the world of others. Masks can also be used to evade identification, for reasons ranging from the liberatory to the criminal. Masks are also cultural emblems of the theater; though no longer worn by most performers as they were in ancient Greece, the dual masks of comedy and tragedy still stand in for the art of performance itself.

British conceptual artist Gillian Wearing asks us to ponder the many social and psychological performances of masks in her current exhibition Life: Gillian Wearing at the Cincinnati Art Museum, part of this year’s robust FotoFocus Biennial across the Cincinnati region. Wearing’s practice, which spans many media, earned her the prestigious Turner Prize in 1997, and is collected in major institutions all over the world, is interested in questions of identity at the boundary of public and private, personal and universal, performative and authentic—in short, in the liminal space of the mask. The small show at CAM features seven artworks that engage photography or video, including four new pieces making their world premiere in Cincinnati, though it would be an oversimplification of her work to limit it within prevailing definitions of contemporary photography. Her most well-known series, for example, Signs that say what you want them to say and not Signs that say what someone else wants you to say (1992-1993), which is sadly missing from the show, is as much a work of relational aesthetics and collaboration with members of the public as it is a series of photographs. Wearing employs lens-based media less for pictorial goals or as documentation than as a means of activating a set of relational and performative vectors between artist, subject, and viewer. In her words: “I’m interested in process, I’m interested in people, but I can’t bear the idea of the technology being something that represents me.”[1]

Dancing in Peckham (1994), the earliest work in the show, plays on a small monitor in the gallery and features a single shot of the artist comically dancing silently in a public shopping mall in London. Clashing with the reserved movements of shoppers around her and prompting suspicious glances, Wearing’s uninhibited movements prompt feelings of liberation, embarrassment, and confusion and ask us to question why certain behaviors are coded as belonging or not belonging in particular places. Though this was the only work in the show that could be understood in the context of performance art (and the only one where we see the artist not wearing some kind of mask), it underscores how identity is understood as essentially performative throughout her work.

Left to right: Gillian Wearing, Me as an Artist in 1984 (2014), Me as O’Keeffe (2018), and Me as Madame and Monsieur Duchamp (2018), chromogenic and bromide prints. Installation view of Life: Gillian Wearing at the Cincinnati Art Museum, October 5–December 30, 2018. Courtesy Cincinnati Art Museum.

Wearing similarly presents herself centrally in front of the camera in the four large still photographs in the exhibition—the works that most resemble what viewers anticipate seeing at a FotoFocus show. Instead of radically exposing herself in a public space, in these highly staged images she peers out from over-sized eye holes in otherwise uncannily realistic masks of her artistic forebears. Three of these works feature the artist in the guise of famous figures from the history of western art, donning the mask as a means of ritual ancestor veneration and spiritual transformation. The selection is not simply based on people she admires, however, as each of these artist’s public images and self-portraits were as intrinsic to their legacy as their artistic production. The tropes of artistic identity employed in her source material already push the boundaries between inner self and outer shell, making her masked performance an amplification as much as a subversion. Dürer’s iconic self-portrait from 1500 was a revolutionary image of an artist as a divine creator, arguing that artistic identity comes from an inner source of genius rather than a learned craftsmanship. Duchamp’s dual images (taken by Man Ray) as both himself and his gender-bending alter ego Rrose Sélavy deliberately thumb their nose at Dürer’s claims to any essential inner self or genius and subvert expectations around authorship, originality, and gender expression. Wearing’s occupation of these iconic images of male artists (or of a male artist dressing as a woman) are meticulous. Textural details of hair and fabric sink these works deep into the uncanny valley.

The black-and-white photographs of Georgia O’Keeffe taken by her husband, photographer Alfred Stieglitz, (none which are not directly quoted in Wearing’s image) are already entwined within complex cultural formulations of how women make and appear within works of art. The famous photographic series (which some scholars contend was a performative collaboration between partners, others a proto-#MeToo exploitation) cannot be separated from Stieglitz’s problematic, biologically-determined praise of O’Keeffe’s genius, often claiming that her imagery came from “the womb” or her inherently feminine intuitions. Breaking from this archive of imagery, Wearing instead imagines a new, defiant pose for O’Keeffe and projects an early Stieglitz photograph behind her, transforming the source imagery into a grainy backdrop for the perfectly articulated textures of her historical costume.

These photographs of the artist in disguise, in their meticulously composed images culled from a shared visual archive, seem to recall the work of Cindy Sherman: they ask questions about gender, originality, and artistic identity using the artist’s body. Sherman’s work, however, most often achieves a near-complete erasure of Cindy the person, whereas Wearing asserts her presence behind the mask—not in the sense of the genius self-portrait, but rather as a performer. The titles Me as Dürer, Me as Madame and Monsieur Duchamp, and Me as O’Keeffe (all 2018) speak in the first person and underscore the tension between self and costume. The fourth mask photograph, Me as an Artist in 1984 (2014) asserts this connection to the personal and connects to Wearing’s earlier series donning masks of members of her family. Quoting a personal snapshot at the age of 21 instead of the art historical canon, this work engages an entirely different, vernacular archive of photographic self-presentation and alludes to the intense “prick” of time’s progression we feel when looking at photographs of our younger selves.[2]

Gillian Wearing (b. 1963), Britain, Snapshot, 2005, 7 videos for framed plasma screens, 6 minutes 55 seconds. Installation view of Life: Gillian Wearing at the Cincinnati Art Museum, October 5–December 30, 2018. Courtesy Cincinnati Art Museum.

The same elegiac tone and vernacular source imagery inform Snapshot (2005), the largest installation in the show, and the only work where Wearing remains behind the camera (an odd curatorial decision for an artist who is just as well-known for her work documenting the thoughts and images of strangers as of herself). Snapshot features seven framed monitors, each containing a looped video of a girl or woman based on a photograph from a particular stage of life and a specific historical period. Each image appropriates the visual codes of family photographs, reminiscent of photographs of my own family and the preciousness of those personal archives, yet the multiple sitters and chronological span in the gallery read less like a personal photo album than a cultural one. Over headphones an elderly woman whose lifespan corresponds to the stages of life and historical periods quoted in the videos reminisces about her younger self and complains about the inconveniences and invisibilities of old age, her singular verbal testament stitching together the shared photographic archive recreated in the videos. “I’ve walked in shops before now, and they’ve literally, walked away from me to serve somebody else,” the woman recalls, “An that’s how life goes unfortunately—if you’ve got a pretty face, er, you know, you get away with murder. Um, not that I’ve become a pensioner, I’m not even noticed. I’m…ignored, in fact.”[3] Listened to over headphones while images of subjects strain to hold poses or otherwise shift and move while adopting particular established photographic conventions of women-being-looked-at, this testimony of women’s (in)visibility at various stages of life exposes the psychic damage of the masks our culture asks women to wear throughout their lives and painfully underscores the many ways in which women’s experiences and memories have been erased or silenced in recent events.

Gillian Wearing in collaboration with Wieden+Kennedy, Wearing, Gillian, 2018, color HD film with sound, 5 minutes. Installation view of Life: Gillian Wearing at the Cincinnati Art Museum, October 5–December 30, 2018. Courtesy Cincinnati Art Museum.

The most current work in the show, set in a darkened space on the other side of the diagonal wall that hosts Snapshot, is the short film Wearing, Gillian (2018), completed at the London studios of the advertising agency Wieden+Kennedy and with their collaboration. Like much of her other work, this project involved an open call to the public to perform identity. Only in this project Wearing asked participants to play herself and the masks in question were created through artificial intelligence and digital imagery. A set of actors spanning various ages and genders deliver lines about identity, only their faces have been replaced by a “digital mask” of Wearing’s. The seemingly-improvised script appropriates codes of the confession and the commercial, constantly destabilizing what’s true and what’s not, and the faces are similarly unsettling, being at once humorous and unnerving. The slick style of the film inherited from its advertising collaborators—its poppy score, zippy editing, and white, space-less backdrop—never let any of the work’s weighty philosophical questions land, instead moving us along until the final conclusion where we see the actual Wearing for a brief moment in an existential scream. The film deftly demonstrates Wearing’s themes of masking and identity through the employment of a new technology, but stops short of engaging machine vision on its own terms and asking what new systems of power, performativity, and public and private lives are part this new visual regime, as in the work of Hito Steyerl or Trevor Paglen. The film instead is a provocation, an introduction, much like the advertisements produced by her collaborators, leaving us (or me at least) wanting more.

Wearing’s employment of physical, virtual, and cultural masks in the seven works selected for Life: Gillian Wearing destabilize our shared commercial, vernacular, and art historical image archives, connecting to the theme of this year’s FotoFocus Biennial, “Open Archive.” Though perhaps leaning a bit too heavily on a photographic definition of Wearing’s practice, overlooking the importance of her relational work in her exploration of life, this exhibition hopefully expands the definition of what lens-based art will be included in this growing regional event.

–Annie Dell’Aria

[1] “Interview with Donna de Salvo,” in Gillian Wearing, eds. Russell Ferguson, Donna de Salvo, and John Slyce (London: Phaidon), 1999, 15.

[2] Roland Barthes referred to this as photography’s “punctum,” that element which pricks the viewer with its nearly indexical relationship to the real (and thus to the passage of time and to death). Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida: Reflections on Photography, trans. Richard Howard, First edition (New York: Hill and Wang, 1982).

[3] Transcript of Snapshot in Gillian Wearing and Daniel F. Herrmann, Gillian Wearing (London: Ram Publications, 2012).