High modernism is well over a century old by now, and its roots are even older. How could that even have happened? The Phillips Collection in Washington D.C. was the first American museum devoted to modern art, opening in 1921, some eight years before MOMA. Though the title of the loan show at the Taft suggests that it will feature American art of about 40 years (from the late 1880s through late 1920s) to take us to and through high modernity, it actually starts a bit earlier and ends with works a good deal later. The Collection at the D.C. mothership covers European as well as American art, and starts chronologically as early as El Greco (of whom Duncan Phillips once wrote “It is possible to be classic or romantic, realist or abstractionist, impressionist or expressionist in a baroque way”); in addition, it continues to collect, primarily in contemporary art. The show at the Taft ends with works from the late 1960s and begins with a gallery of pre-moderns to help set the stage for the long arc of modernity as American painters found it, followed it, adapted it, and eventually led it.

Midway through the show, there is a detailed wall posting explaining the natural fit between The Phillips Collection and the Taft Museum. Both are private collections that are now public museums (though Phillips seems to have collected expressly with the idea of sharing of his tastes with a prospective audience of museum-goers in mind), housed in what used to be their residences. The posting also suggests some clear differences in what interested each of their founders. The Taft collection is, of course, predominantly classic and historical in nature; the Phillips is predominantly about the new. (Almost two dozen of the works in this show were purchased within four years of having been produced.) It points out that the Taft collection is largely frozen in time, while the Phillips continues to grow and acquire. It is also true that, for better or worse, the Tafts are silent partners with their visitors; whatever they thought and hoped in purchasing their pieces over the years is not readily accessible. Phillips, on the other hand, loved nothing better than to share his opinions and convictions; his museum was to present not just a personally curated collection of modern art, but would illustrate his ideas about it. He comes across as affable, opinionated, and something of an optimist when it came to art, artists, and modernity.

It is hard not to read the show, in its individual parts and taking the 54 paintings as a whole, as Duncan Phillips’s strong-minded reading of what constitutes modernity, and why it’s worth dedicating a museum to it. In developing the Collection, nothing was left to chance or to committee. This is his show; there are things he wants to tell us about modern art, and he has the floor. To Phillips, modernity was not just the historical period in which he found himself—it also constituted an implied value judgment; the closer an artist’s work got to it, the more significant it was. From where Phillips stood when his ideas and sensibilities were being formed, abstraction must have felt like destiny. Various forms of realism were way stations along the path, stages certain artists and whole movements would have to pass through on their ways to truer callings. Phillips was demanding but patient.

The show starts with a room of precursors. There is a relatively early Inness, “Lake Albano” (1869), a work that is an odd choice for this show. It is not one of Inness’s considerably more abstract and luminous later works, and seems in general to be more a figure-crowded vacation scene. It does not seem allied to the cornerstones of early to mid-19th century American landscape, in which the Collection seems to have little interest. The wall tag suggests that Inness was drawn more to the idea of “civilized landscape” than to rugged wilderness, and Phillips seemed to have felt the same attraction throughout his years of collecting. Phillips’s reading of modernity, for example, does not make room for Thomas Cole or Frederic Church or even Martin Johnson Heade or really anything that seems too Hudson River School or Luminist, though some scholarship of the past few decades has proposed interesting links between the sublime American landscape and abstract expressionism. When it comes to the American West–the sort of subject matter that has typically elicited the American appetite for grandeur–Phillips chose to acquire instead a work like Twachtman’s “Emerald Pool” (c.1895). Only from the top quarter or so of the painting would we see the grand tree line and the distant mountains, and therefore have any sense that the painting was done in Yellowstone. Phillips seemed to have turned his back on things that rely on scale and distance, and preferred an intense exploration of color (he seemed to have a thing for ochre) and thoughtful and expressive brushwork, and for design in which abstraction was already lurking.

The precursors also include a pretty great Eakins portrait, “Miss Amelia Van Buren” (c.1891). It was by far the best portrait in the show, which suggests that either Phillips’s eye was not as strong when it came to portraits or that in the history of modernism, portraiture constitutes a vexing category. Van Buren was one of Eakins’s students while he still taught at the Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. (The story has it that it was Eakins’ partial disrobing in front of her to answer a question she had raised about anatomy that led, among other causes, to his being fired.) The inclusion of the Van Buren portrait seems to be an homage to the aspect of modernism that takes its realism unblinkingly, something we will not see again chronologically until some of the later cityscapes. Eakins, who liked to study how things were put together, has painted every seam in Van Buren’s elaborate dress as if they constituted some part of her armature or exoskeleton. Like many other Eakins portraits, her gaze is averted; she is confronting her inner thoughts, not the painter or the viewer. Though some of Eakins’s men seem to have a nobility in their distant stare, here the painting seems to focus on the odd discomfort of being female that Eakins either captures or imposes on many of his women models.

Winslow Homer, To the Rescue, 1886, oil on canvas, 24 x 30, The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C. Acquired 1926

As great as the Eakins is, I would imagine that Winslow Homer’s “To the Rescue” (1886) was closer to Duncan Phillips’s heart. Phillips was drawn to this painting, we are told, because it “renounced story and sentiment,” though it might be more accurate to say that it embodies a complex attitude towards narrative. Two women are facing uncertainly out to a stormy sea while a man with rescue gear is running up behind them. Are the women searching, hoping, or already mourning? The man is carrying rope, but can it possibly be enough to be of use for a rescue in a violent sea? I’m not sure that there is no sentiment or storytelling here, though both are evocative and equivocal, rather than explicit. This is the modernity of naturalism, driven by a sense that nature is far too indifferent to us to be our partner. The painting’s focus is on the wall of boiling waves pounding on the shore, possibly alarmingly close to our three figures, and the water is rendered with a vivid abstraction.

Albert Pinkham Ryder, Moonlit Cove, 1880s, oil on canvas, 14 1/8 x 17 1/8, The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C. Acquired 1924

But I think that in laying out the origins of American modernity, Phillips perhaps found that Albert Pinkham Ryder’s “Moonlit Cove” (1880s)—one of nine Ryders that he owned—was even closer to his heart. Though there may be a ghost of a narrative in it, the painting is remarkable for the elegant way it has set down a series of abstract, sensual shapes to suggest the night sky over a coastal landscape, all as flat as pieces of a jigsaw puzzle, showing us the ways that each part comes together to make up the whole. It has natural links to the landscape-inflected abstraction of the Diebenkorn and especially the Frankenthaler in the installation’s final gallery. The Ryder was modern enough to have been shown at the 1913 Armory show, some 30 years after it was painted. It is hard not to see a clear line from the Ryder to the vision of Georgia O’Keeffe or even Milton Avery, for whom the natural world was the stepping off point for sensuous abstraction and evocation of things beyond the natural forms with which the painting has started.

John Henry Twachtman, My Summer Studio, c. 1900, oil on canvas, 30 1/8 x 30 1/8, The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C. Acquired 1919

The Impressionist section of the show is very strong, considerably supported by remarkable contributions from Twachtman. American Impressionism often raises collateral social issues, celebrating the ability of a leisured class to stride in the sun. We see some of that in Childe Hassam’s “Washington Square, Spring” (1893) where, despite the presence of a street sweeper off to one side, the painting mostly presents a world shaped by processions of carriages and strollers, straw hats and top hats. This is not the place to litigate the complex relationship between landscape painting and private property (though that is a reckoning that always lurks), but this section of the show has paintings that are both sensational in execution and modest in subject matter. Phillips valued the brushwork of the Impressionists. Julian Alden Weir is shown to great advantage with “The High Pasture” (1899-1902), which has some of the tightly coiled energy of the Ryder, with its broad blocks of sensual shapes fitting tightly together. It is all the more remarkable for Weir’s decision to make the large central portion of the work devoid of any detail besides the busy marks of his almost monotone brushwork. The brushwork of Twachtman’s “My Summer Studio” (c. 1900) is even more remarkable. The artist’s marks and colors are wild and have a life and logic of their own. The rocks in the foreground, the low cliff in the background and the water in between are painted with the freehand energy of pure abstraction; if it weren’t for a few trees, a handful of grasses, and the distant house, one would be hard put to know why it couldn’t have been painted some 50 years later. It is a dazzling study of colors so intense but varied that it is hard to say to quite what season they belong. It is a slam dunk to see (and celebrate) modernity in such a work.

The Collection is drawn to paintings that present certain sorts of narrative, generally falling under the heading of activities in the “civilized landscape” that Inness favored. There is a luminous early Rockwell Kent, “The Road Roller” (1909), where a huge metal drum is being drawn by a team of six horses to flatten down the snow (to accommodate sleighs) across the crest of a New Hampshire hill. “The Road Roller” is probably a modernist example of what in the prior century would have been called a genre painting, which is another way of saying a painting that depicts people at work. The roller itself seems to require four men to manage it (some more intensely and actively than others), and they are high up on the machine silhouetted against the clouds. There is something unabashedly epic about the horses, men, sky, and shadows; there is also an acknowledgement of an impressive and ingenious piece of civic machinery. Phillips is said to have responded to Kent’s heroic and classicizing sensibility because it also allowed for what he called “modern complications.”

As the century moved on, Phillips seem to have been drawn to landscapes that were less civilized, but which provided the opportunity to see the modernists’ merger of paint and the thing being painted, a hallmark of the growing movement towards abstraction. There is, for example, a terrific Marsden Hartley, “Mountain Lake—Autumn” (c. 1910) where each brushstroke is like a fabulous, gem-bright tessera in a dazzling mosaic, and a startling landscape by Harold Weston, “Winds, Upper Ausable Lake” (1912). Full disclosure: I had never heard of Weston before, and I see that the Phillips Collection owns twenty of his works. This suggests that Duncan Phillips was not cautious about exercising his taste; he supported many of the artists he collected indirectly, by purchasing and displaying their works, and some (including Kent) directly, by paying them stipends. “Winds, Upper Ausable Lake” is a remarkable painting, allowing us to feel the lake-long gusts of wind rippling the water’s surface, and putting us in mind of how close to spirit the wind can be. Paintings like these serve to remind us that while there is an objectivist streak to modernity, a concern for the scientific, the empiric, and the severe, modernism could also be seen as a natural extension of romanticism. This is probably the way that Phillips himself saw things, looking for works that, while moving towards abstraction, suggested both spiritual power and evoked emotional responses from the viewers.

He was also drawn to the kinetic and the plastic. Though there was only one sculpture in the show (a Calder hanging so high up that many visitors might miss it—I wish it had been joined, for example, by the excellent David Smith that The Collection owns), several of the paintings demonstrate modernism’s interest in three-dimensional work in the development of paintings with thick impasto. There are some paintings that are done practically in low relief. Interestingly, impasto brushwork is one of the identifying signs of the Munich School, but the Collection does not own any Duvenecks. But impasto—the moving of the painting surface into three dimensions—can also be one of the developments of abstraction, and that is where the Collection is, as always, strongest: works on the border of ever purer abstraction. John Marin’s “The Sea—Cape Split, Maine” (1939) is a remarkable picture: if it were not for the reassuring presence of the horizon line (another reminder of the potentially rich connections between abstraction and landscape), it would be as practically as non-representational as the swirling shapes of a more lyrical de Kooning. Painted with thick oil strokes, lines, and patches—and significantly different from his many watercolors–there are portions that are almost sculptural in their refusal to lie still on the canvas.

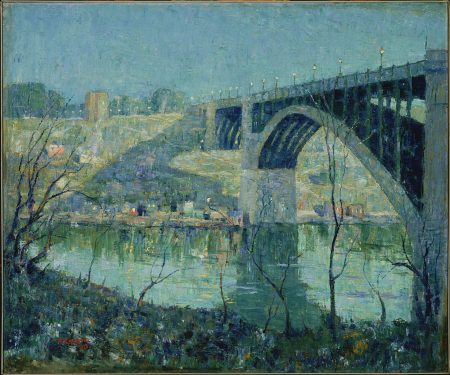

Ernest Lawson, Spring Night, Harlem River, 1913, oil on canvas, 25 1/2 x 30 1/2, The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C. Acquired 1920

Modern art took on the city perhaps in part because it was where the value of modern culture could be tested, and the Collection owns quite a few impressive cityscapes. When Duncan Phillips thought about the city from his perspective in Washington D.C. near Dupont Circle, he almost invariably thought of New York. Some of these paintings are quiet with a spirit that can be peaceful or uncanny, and some are crowded with people, reflecting the rough and tumble of everyday life. There is a terrific Ernest Lawson, “Spring Night, Harlem River” (1913), which shows the Washington Bridge connecting Manhattan to The Bronx. Celebrating the romance of the city as surely as Twachtman celebrated the romance of the countryside, the painting shows the bridge, a marvel of gentle, geometric engineering, when it was just 25 years old. It is one epitome of Inness’s “civilized landscape”: though we cannot see anyone on the bridge, the electric lights—this is, after all, the modern city—cross the bridge and line the street way off into the distant maze of buildings on the far shore. A cityscape is a good place to deal with economic disparities, and this one does it very eloquently. At the street level across the river, we see rows of sturdy brick apartments; down closer to the water, there are mostly wooden shanties, but they are bound together by the light of the spring evening and the pattern of lights and abbreviated shapes that tell us as much as we know about the buildings.

John Sloan, Six O’Clock, Winter, 1912, oil on canvas, 26 1/2 x 32, The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C. Acquired 1922

John Sloan’s almost contemporary “Six O’Clock, Winter” (1912) is as bustling as the Lawson is tranquil. Then as now, 6 p.m. is rush hour in Manhattan, and there are crowds of people lining up to board the El to finish their commute; even greater crowds tumultuously fill the streets below. (The category of the cityscape enabled Phillips to add more diversity to his sense of modernity, which tends to be heavily dominated by white men. Though the Collection has rich holdings in Jacob Lawrence, whose works did not make the trip to Cincinnati for this show, there is a striking “Parade on Hammond Street” [1935] by Allan Rohan Crite, showing musicians marching through an African American neighborhood in Boston.) The work day is over and Sloan’s people are pointed in all the directions that will take them home, passing in front of shops open for the last customers of the day, while other people have work that still needs completing. There is an endlessness to work without the usual accompanying dreariness; like the men riding on Kent’s giant snow roller, work was both serious and still something of an adventure. It is striking how many women are apparently in the modern work force, and how freely and easily men and women mix and mingle in Sloan’s urban environment (unlike, say, Hassam’s, where people seem to be more like solitary statuesque clothes horses). It is a dense and incandescent world, with the warm glow of electric lights everywhere under the deep, cool fading blue of the sky. Both paintings are trying to capture the romance of the city, relishing the awesomeness and beauty of things made by man, and the accommodations people make to fit so many of us together into it.

Edward Hopper, Sunday, 1926, oil on canvas, 29 x 34, The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C. Acquired 1926

There are two strong Hoppers in the show. Hopper’s blank-faced figures seems to invite audiences to project themselves—and, frankly, their dissatisfactions—onto them. In “Sunday” (1926), a shirt-sleeved figure sits by himself on the wooden sidewalk in front an empty store with sleeve-garters on his arms, smoking a cigar. I heard gallery-goers’ comments about his loneliness and isolation, encouraged perhaps by the wall tags, but must admit that I wasn’t buying it. It is true that he’s not a member of the idle wealthy class, but to me, he seems more likely to be an employee of one of these stores at rest or on his break, not in desolation. The store in front of which he is sitting is empty but the one next to it has a large green shade drawn. It’s open for business—just not right now. I see the seated man as someone having a private moment in a public space, as many of Hoper’s figures in his early paintings do. After all, as the title tells us, it’s Sunday. If I were to project my own emotional baggage onto the cigar smoker’s relatively expressionless face, it might come out something more like “Hey, folks, it’s Sunday. We’re closed now. I’m on my way home as soon as I finish my cigar. See you tomorrow.”

Edward Hopper, Approaching a City, 1946, oil on canvas, 27 1/8 x 36, The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C. Acquired 1947

I found myself responding to a less familiar, more recent Hopper urban scene, “Approaching a City” (1946). A set of train tracks is about to descend from street level into a dark tunnel. Who knows where it will come out? Beyond the rain- and rust-stained wall separating the train from the street (itself a little like an abstract canvas), we see a row of brick houses and across the street from them, part of a large concrete building with tall smokestacks–a factory, presumably, of some sort. The painting puts us at the intersection between three ways to experience the city: you live there; you work there; you’re just arriving, or perhaps passing through. As with “Sunday,” it is the viewer who is the outsider. (Is this another strand that drew the attention of Phillips, something we have seen as early as the Eakins portrait?) It is striking to pair this painting with the Sloan, the latter showing the tumult of the crowd, and the Hopper showing the eerie, perhaps uncanny peacefulness well before or well after rush hour. Is it too anxiety-provoking? When the train comes, it may well get swallowed up into the dark maw of the tunnel. But we’re not on the train. And we see curtains and shades in every window of every dwelling, each drawn in a different way, assuring us that people are living there and are capable of expressing their autonomy, even if they don’t choose to share it with us. They’ve got their privacy, and as a viewer from below, I’ve got mine—another private moment in public.

It would have been a sufficient success for Phillips to have suggested some of the lines by which you can get from Ryder in the 1880s to Georgia O’Keefe’s “Ranchos Church, No. II, New Mexico (1929) or Augustus Vincent Tack’s “Canyon” (c. 1923-4) or Stuart Davis’s “Egg Beater No. 4” (1928), all of which feature rich outlines of sensuous, painterly shapes lyrically interlocking like pieces of a puzzle. But The Collection’s ambitions include continuing the story of the American modern to the present day and beyond, even though this show extends the narrative only through mid-century. There is a stunning Guston (before his electrifying return to figuration), “Native’s Return” (1957), with his characteristic pile of geometric shapes in colors close to primary, painted in thick impasto, sitting over a background of atmospheric, painterly pastels. It is plain to see that Guston never lost interest in shapes that are almost identifiable; though wholly abstract, if someone told you that it was inspired by a city scene—or perhaps a landscape—you would not be surprised. Do the shapes hold together enough to suggest an abstract sculpture emerging from a pastel haze, or will the whole pile of painted things, unattached to each other, collapse in a chaotic jumble?

As its title suggests, Richard Diebenkorn’s “Berkeley, No. 12” (1954) is right at the edge between representation and non-objective. The sets of horizontal and diagonal lines, the painterly patches of greens and ochres, are classic signs of a vision that includes both topography and abstraction. Together, they suggest that once again we are in the presence of the civilized landscape. It is interesting to take a closer look at the picture’s surface. For whatever reason, the surface of the paint is starting to crack, reminding us of the Ryder. But if the key to the Ryder is its spirituality and profound placidity, the Diebenkorn is also an homage to the furious energy of the artist at work. Stuck here and there on the canvas are bristles from the brush, shed, presumably, while the artist was scrubbing the surface with loose, wet paint. The brushwork is as vigorous as the Twachtman “Summer Studio.” But if the Twachtman is about how much color can be loaded onto the toe of the brush, the Diebenkorn shows the artist drawing with the brush’s opposite end. The brightest marks of the Diebenkorn come not from the paint, but from the artist’s energetic hand, scraping paint away with the point of the handle, the opposite end of the brush.

It is hard not to honor The Phillips Collection for its nerve and audacity of trying to explore the ways that Duncan Phillips’s vision continues to be relevant. As a museum, it is working hard to envision a more inclusive modernism, allowing crowds of different sorts of artists to gather under a larger tent, and moving from one art historical narrative to many, linked, hopefully, by their connections to the powerful vision of artists and their viewers and collectors over the last century and more. Phillips himself does not seem to have been drawn to minimalism or the impersonal. He had faith in the human eye and hand, and especially valued work that freely showed the artist’s autograph marks. It is fair to say that he had confidence in painting, and generally saw modernity as something that affirmed being human. In this show, at least, it seems that there is nothing that you can’t paint your way out of.