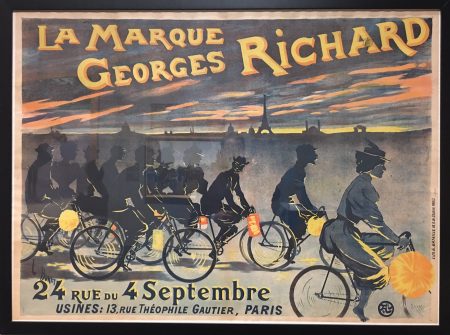

The visual richness of Paris during the Belle Epoque would have followed people wherever they went, even out of doors. Posters must have been everywhere, depicting products for sale and announcing events and attractions both large and small on lithographed newsprint affixed to walls, fences, and kiosks specially designed for the purpose. The marketing of pleasure was in high gear. And posters are everywhere at the CAM’s “Paris 1900” show. Georges Meunier designed one for “The Aquatic Roller Coaster Known as Niagara Falls” (1895), a type of amusement park ride perfectly familiar to us: small boats that hold perhaps a half dozen people are lifted high off the ground above a lake, speed down a steep constructed chute that winds high through the treetops of a park, and land in the water at the bottom with a splash and much whooping. Another poster by Jean-Leonce Burret (1890) advertises a type of bicycle made by Georges Richard by showing ten or so people cycling in a sociable group at dusk not far from the center of Paris; the Eiffel Tower, which had been open for only a year when the poster was made, is in the distant background. Attached to every bicycle is a Japanese paper lantern lit up, I assume, by electric batteries.

Bicycle makers like George Richard would, within a few years, go on to become automobile makers, except, of course, for those who went on to pioneer powered flight. That’s how direct the path is between bicycles and modernity. These two posters can be taken as indices of modernity in many other ways as well. Both images feature electricity—the flume ride is a night scene, illuminated by tall lamps: electric infrastructure and portable electricity are two of the co-stars of the whole show. Both are about specifically urban pleasures in a way familiar to urbanites to this day: they depict activities that could only happen in the city, but involve getting a little distance from the crowds. Both are night scenes, but illustrate the taming of the darkness; outdoor fun does not stop at night. Perhaps most significantly, women are full participants in the pleasures. Four of the ten bicycle riders are women—I took the implication to be, in part, that they are part of a mixed group and not merely paired off with husbands or lovers—and in the roller coaster ride, women outnumber men both in the boats and along the shore. Modernity—or French modernity, in any case—is very much about the marketing of round the clock fun to all comers.

Well, perhaps not all. The museum’s show documents—and it is very much a documentary show at least as much as it is a show of fine pieces of high art—the democratization of pleasure–up to a point. Formerly aristocratic privileges are becoming readily available to the upper middle class (the haute bourgeoisie is very much at the show’s center, along with a bohemian class that is harder to place on a strict economic scale), and upper middle class luxuries are becoming increasingly available to the middle class. The working class make relatively fewer appearances, and the foreign or exotic among the Parisian population are more likely to be the objects of spectacles than to be spectators. There are places where the social classes mingle—sometimes on busy streets, sometimes while attending popular entertainments, but also in the dark alleys and brightly lit sidewalks where women find themselves the providers of pleasure, rather than the consumers. Though the show is subtitled—rather blandly—“City of Entertainment,” it is surely a show about things that can be had for ready money. One measure of modernity is the commodification of pleasure. Manufactured goods (like art nouveau glassware), theatrical entertainments (such as the Moulin Rouge), and works of art (the sorts of posters that could be found on walls and kiosks and in galleries) were available to a steadily broadening audience at reasonable prices. But the show also amply documents the commodification of sex and sexually-charged pleasures, often to the same sets of consumers, at similar rates.

The exhibit centers around two grand (and possibly grandiose) international expositions in Paris, the 1889 fair honoring the centennial of the French Revolution, and the World’s Fair in 1900 that celebrated the achievements of the 19th century. One unspoken purpose of these vast exhibitions was to put the miseries of the 1870 Franco-Prussian War, and the short-lived Paris Commune that followed, behind the nation. Judging by the objects, drawings, and photographs in the show, the fairs were architecturally a striking combination of the old-fashioned and the new, with old-fashioned domed palaces that look like St. Peter’s Cathedral on the one hand, and the Eiffel Tower (1889), that looked like nothing that had been built before, on the other. Like many international fairs, then and now, they were urban Disneylands filled with things like reproductions of Norwegian villages and Venetian villas. The American Pavilion would be hard to distinguish from a turn of the century post office in any substantial Midwestern city. Much of the architecture (and a good deal of the CAM exhibit in general) helps to remind us that the Paris of 1900 looked backwards at least as much as it looked forward. Putting art nouveau floral objects in the vicinity of late Victorian over-decorated ones helps remind us much of art nouveau had some extremely traditional roots. Many, if not most, of the paintings in the show owe at least as much to the formal training and expectations of the Salons and the French Academy as they do to the burgeoning influence of Impressionism.

Though most of the complex and fraught political texture of the Third Republic is missing from the show, there are certainly some tributes to labor. There is a model for a monumental frieze by Anatole Guillot (1900) honoring the rural and urban workmen who made the comforts of Parisian life possible. These are the years of the building and opening of the first branches of the Paris Metro and there is a painting by Gaston Brun of the “Construction of Line 1 of the Metro” (1899) showing two muscular workers, stripped to waist, laboring at a wall of dirt and rock with pickaxes, illuminated only by a single electric bulb. Georges Souillet, an interesting painter of the urban scene who was entirely new to me, shows in his “Construction of the Metro” (1905) teams of workmen being supervised as they tunnel under the Place Saint Michel. The Paris above the street level is highly traditional, with domed buildings and a gothic spire in the distance; the foreground shows some of the individual workmen with a vast steel armature of construction machinery towering over them.

The modernity of Paris is captured in the visual arts by the omnipresence of electric lights, both indoors and outdoors. Dozens of garlands of lights swagged from trees create a dazzling artificial day in William Samuel Horton’s “Nighttime Festivities… at the Elysée Palace” (1905), enabling the carefully curated guest list to feel like royalty who can command the sun. The impact of George Roux’s “Nighttime Festivities…Under the Eiffel Tower” (1889) comes from the virtually endless rows of incandescent bulbs that delineate the Tower’s arches and are tucked along the rooflines of most of the buildings in the distance. It would have been interesting to know a little more about the development of the electric infrastructure for a city as large as Paris. It seems to have happened very quickly. Less than a decade earlier, Paris had hosted the first International Exposition of Electricity; three years before that, a modest couple of streets had been lit for an exposition in 1878. But the pace of change was very fast. By 1907, a former theater was rebuilt as a huge movie house, the largest in the world, holding 5500 customers. (In its current configuration, Cincinnati’s Music Hall holds fewer than half that number.) Louis Abel-Truchet’s “The Gaumont Palace Cinema” (1913) shows the building brilliantly lit, chasing the night away as crowds arrive for a showing. It is not easy to tell from the painting just who is attending, but it feels as if the audience is socially mixed: some are arriving by public omnibus and some are arriving by private carriages.

Alexandre-Georges Roux (1855–1929), “Nighttime Festivities at the International Exposition of 1889 under the Eiffel Tower”, circa 1889, oil on canvas, Musée Carnavalet, Paris, © Musée Carnavalet/Roger-Viollet

What can we tell about a city and its art forms by the crowds they attract? The evidence in the show suggests that they were only moderately diverse. Henri Meyer, in an illustration for Le Petit Journal (250,000 readers, we are told right on the picture!)(1900), shows the crowd milling around The Petit Palace. Judging by their costumes, there are some Turks, Chinese, and Arabs, and a black man wearing a top hat. But even as visitors to the Fair, they are imagined to be on display. The great woodcut artist Felix Vallotton did an album of prints for the 1900 World’s Fair and all of them are about crowds: watching fireworks, walking past the barker for a Cairo Street exhibit. A huge crowd is being transported to the Fair entrance by the moving sidewalk the Fair futuristically featured, while in another one, men—some with top hats and some with straw hats—plus women with scarfs, and children and enticing squiggles that must represent dogs are all scattering at the onset of a rain shower. In each case, the figures are merely cyphers in a large group.

In Vallotton’s vision of the Fair, there are almost as many women as men in attendance, and this goes to the heart of the CAM exhibition’s argument about Paris in 1900: women had unprecedented cultural presence and significance. Everything depends, of course, on the curators’ selective principles, but we get some insight into the professional accomplishments and competence of actual individual women. (The show’s sampling of idealized women came off, I thought, much weaker.) The entertainer Loie Fuller, who danced in swirling dresses startlingly illuminated by colored electric lights, is represented by a selection of the line of souvenirs she sold. We see Toulouse-Lautrec’s model Jane Avril coolly appraising a proof impression of the cover of “L’estampe originale” that features a lithograph of herself. Lautrec also has a modest lithograph of “The Milliner Renee Vert” (1893) who is confidently absorbed in arranging a hat for display. (Nearby is an actual hat, fashioned by Mademoiselle Mestayer, a remarkable straw confection with ribbons and artificial flowers that has somehow survived since its creation in 1902.) And there is a good deal of attention paid to Sarah Bernhardt, including all the very slender amount of surviving footage of a movie made of her performance of Hamlet around 1900. Even more remarkably, it turns out that Bernhardt was a sculptor of considerable accomplishment with a striking full-size heroic bust of the playwright Victorien Sardou, who wrote the theater piece La Tosca which Puccini later made into his opera. Bernhardt also made a bronze that merges a substantial-looking dagger with a cast of a piece of seaweed collected by the beach where the handle would be.

There is the sense that women—of a certain class, to be sure—were largely free to explore their worlds. In a satiric lithograph by Georges Goursat, who published under the name of SEM, called “Expulsion from Maxim’s” (1901), an oafish top-hatted male drunk in full evening regalia is being firmly escorted from the famous restaurant barely holding onto his glass and cigar. A few women—presumably the ones who blew the whistle on him—look on, partly with irritation and partly in amusement at his ridiculousness and swift punishment. But the implication clearly seems to be that Maxim’s is a place where women, unescorted by men, are entitled to feel safe. In a watercolor and gouache sketch for a larger piece that decorated a Paris theater, Henri Bellery-Desfontaines depicts a weight-lifter showing off his skill–this city of entertainment caters especially to the jocund and robust–before an audience of two exquisitely dressed men and a woman who stare at him from a modest distance. But meanwhile, a younger woman in a well-draped tailored suit is closest to him, her hands in her pockets, one foot up on a small concrete slab, a white sunhat slouched over her face, and she is giving him a pretty direct and careful once-over.

Her suit, we are told, is a loosely fitted split skirt, tucked up under her knees—an outfit designed to be suitable for women to wear while bicycling. (The other woman is more typical of the corseted and sculpted body designed for women; both sets of aesthetic values seem to coexist in the culture.) In this exhibition, we see women attending theater, shopping, smoking, ordering drinks for themselves, riding horses on their own, even driving carriages by themselves down the Avenue du Bois, but especially we see them on bicycles. These are not the so-called high bicycles, but close ancestors of the same bikes we use today: they are chain-driven with handbrakes and feature rubber, inflatable tires (a crucial comfort innovation for Europe’s cobblestone streets), and step-through mounting for women. (Gears would come later.) There’s even a bell on the handlebars. In Edmond Grandjean’s “La Place Clichy” (1896), time is frozen on a wet Paris day at a busy intersection where retail establishments surround a bronze monument. The painting is an homage to the different ways people get where they’re going. There are walkers in the streets and on the sidewalks. People are in private carriages and a woman is being helped up the steps to a double decker public omnibus (which would have cost a mere fifth of a franc). And in the center of the painting, with great equanimity, a woman is riding her bicycle. A wonderful poster by Henry Thiriet shows a pair of women, one the customer and the other the proprietor, at a “Linen Sale” (“Exposition de Blanc”) (1898) going through a pile of garments with delicate patterns. The shop is at Place Clichy; the same monument is visible silhouetted through the shop window. Both women are carefully coiffed, wearing dresses that cover them from neck to wrist, but one is sitting while the other stands, which tells us who is the client. Her purse is slung over the ear of her chair.

A feature of French life in 1900 is that women are comfortable being by themselves, but can also apparently freely associate with women or with men and, for the most part, can do it at most times of the day or night. In Edouard Zawiski’s marvelous “Place Blanche and The Moulin Rouge” (1902), two women are hurrying arm in arm at night across an empty street towards the club. Perhaps they are friends, slightly late for the show? “At the Chalet du Chateau de Madrid…” by Louis Abel-Truchet (1895) shows a peaceful and sociable moment at a popular gathering spot in the Bois de Boulogne. In the center, a woman has dismounted from her bicycle to talk to another woman. The clothes suggest that everyone is economically comfortable. At the surrounding tables, we can see practically every possible combination of people. Men are seated talking with men, but women are talking with women and women are talking with men, sometimes even two at once.

There is a theatricality to everyday life in many of these works, sometimes casual and sometimes frenetic. In Rene Lelong’s grisaille sketch for an illustration of an “Equestrian Tournament at the Grand Palais” (1910), the uniformed gentlemen on horseback frozen in a gallant line—nominally the subject of the work–fade into the background. Our attention is instead focused on the audience in the foreground, a group of men, women, and children (though more women than men) who are filled with life in every way. They gawk; they lean forward; they raise opera glasses to their eyes; they talk to each other. They are highly individualized. The horsemen, by contrast, seem to have been cut out of a pattern. The audience has become the show. When Alfred Smith went to paint the races at Anteuil (1893), he chose to capture the scene when the actual racing is over, and the crowd is busily milling its way towards their transportation. There are soldiers in bright uniforms (unformed soldiers in public spaces seem to have been a feature of life in the city of entertainment). There are women alone, women with men, women with children, and women with other women. This is the spectacle that matters.

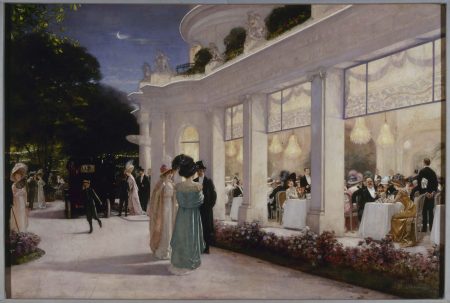

But there is also something edgy about this spectacle. The CAM show is very large (there are some 250 objects in all), divided, as is often the case in the museum’s special exhibit area in the second floor, into two halves. As soon as you enter the half to your right, the tone darkens, and not just because the first room’s organizing principle is Paris by Night. Henri Gervex’s enormous “An Evening at Le Pre Catelan” (1909) is an unsettling work. Dinner service at the restaurant is in full swing with seating indoors and outdoors on a fine spring night. Some couples are leaving and some are lingering, though there are fewer women with other women (and certainly no bicycles) than we have been used to. The floor to ceiling windows are fully open to the outdoors; each one frames a table, like a tableau. The wall tag tells us that one of the women we can see is a famous courtesan; we cannot see whom she is with. But what, then, are the other women? The semiotics for distinguishing between the high-class courtesan and the artist’s own wife, who we are told is also in the painting, are not immediately clear.

Henri Gervex (1852–1929), “An Evening at the Pré-Catelan”, 1909, oil on canvas, Musée Carnavalet, Paris, © Musée Carnavalet/Roger-Viollet

It is not always clear when confusion is intended or not. In Jean Beraud’s “The Ladies of the Night” (1905), a pair of well-dressed but over-made-up women are walking past a gauntlet of wealthy men on both sides, some young and some old, who are plainly inspecting the women as they walk by. One of the women seems comfortable with being part of this show; the other seems miserable. The men, portraits in privilege, are at least as despicable as the women are seedy. It is night; we are in front of a café or perhaps even in a park; there are the familiar strings of electric lights. It is hard to be comfortable with this picture, but at least the initial cast of characters is pretty clear. But behind the two walkers and the four men are men and women apparently happily conversing. The groupings recede into the background almost indefinitely. Is it all a meat market? In a world where good clothes do not guarantee good characters, one has to wonder retrospectively: are all the other couples we’ve been seeing neither more nor less than these? This is a way to measure some of the darkness behind the theatricality of other paintings. We have audiences and performers, and both turn out to be potentially troubling positions.

In one of Fernand–Louis Gottlob’s sketches for a magazine illustration, an elegant woman gazes avariciously at a blazing gemstone literally being dangled in front of her. In another, a man and a woman have gone shopping and he hastens to assure her that he still has plenty of money left for her. The commodification of middle class pleasures is revealed to be potentially toxic. Fernand Fau has a page of cartoons on the subject of love that was printed in the magazine Le Chat Noir; in turn of the century Paris, the world of printed cartoons had become part of the fast-response team to cultural pressures. In Fau’s graphic sequence, a streetwalker brings a man up to her room; they disrobe and disappear; he leaves happily, and she goes back to her position on the street, right back where she had started. But when we were in her apartment, we see that she is (or was) a student, with what seems to be a diploma and even an honorable mention prize of some sort over her fireplace. The exhibit does not make light of prostitution. Theophile Steinlen has an ominously dark etching of “Two Gigolettes and Two Gigolos”—two whores and two pimps—and there is nothing of gay Paris about them as they negotiate in the night. In a wonderful painting of two women leaving a Paris store on a rainy day, the wall tag notes that knowing how to raise your skirt (so as not to drag it in the rain and mud) was a gift particular to young Parisian women. But it seems an alarmingly short step from that to Louis Abel-Truchart’s lithograph “Quadrille at the Moulin Rouge” (1902) where four young dancing women who could be dressed in street clothes are lined up to lift their skirts for a large crowd of standing men, pressing in very close, leaning in to study the spectacle of what can be seen. The exhibit traces a long, complex cultural circle. Is this the end point of theatricality, display, and freedom?

The show has some significant omissions in the story it hopes to tell. It was interesting that there were several places where the new form of film was given space. The largest crowds I saw in my two visits were gathered around a screen watching a colorized version of Georges Melies’s famous silent film “A Trip to the Moon” (1902). But where was the space that could have been given to sound recording, a technology at least as well-developed around 1900 as film? I also missed the sense of political turbulence that was as much part of the social and cultural scene as the fairs and exhibitions were. And while the artist Jean-Louis Forain was represented by a number of works including a pair of lovely life-size mosaic adaptations of quick sketches he had made of street characters, there was no sign or mention of his role in the anti-Dreyfus campaign, when he produced virulently anti-Semitic cartoons for magazines very similar to the ones whose work was on display. Indeed, I caught not one mention of either Zola or Dreyfus, though that whole ongoing scandal, which began in 1894 and didn’t fully end until almost a full decade later, tore apart the sense of community among the artists and craftsmen who made up the bohemian population in the Belle Epoque. The show could have benefitted from some candor about this. More than once, I found myself uncomfortably scanning the wealthy idlers in some of the works and wondering whether there was maybe something a little too curved in the nose of this one, or whether that one’s beard was just a bit too curly. The Dreyfus scandal raised serious questions about the underpinning of all the sophistication and worldliness on which Paris at the turn of the century congratulated itself, and makes one reconsider at least some of the cultural gaiety celebrated in the show.

There are some remarkable stand-alone paintings in the show, including Maximilien Luce’s “Sacre Madame Slag Heaps” (1897), which brings a sharp post-impressionist eye to some of the materials required by the industrial revolution that helped build and run Paris, and Charles Camoin’s “Portrait of my Mother in her Salon” (1897). An 18-year-old Camoin, another artist who was wholly new to me, painted his young mother in her home with a book or portfolio in her hands as she relaxes on a startlingly abstract couch. If, on the other hand, several of the other paintings in the show seemed more like the sort of things you’d expect to find on a restaurant wall, it’s because that’s where, in fact, you would have found them. Basically, this was a show about cultural history, and cultural history is less discriminating than a pure painting show. It requires and elicits less connoisseurship, but its cumulative effect can be powerful and persuasive. In such a context, fine arts and easel painting do not have a particularly privileged status. I found myself thinking that I would have sacrificed a couple of the paintings for a closer look, for example, at the actual workings of one of the thousands of light bulbs in painting after painting.

But the show had, I thought, a complex set of issues it addressed well, especially in what I took to be its core issues of gender, sexuality, and class liberations and tensions. We can feel this particularly strongly in a haunting painting by Jean Beraud, who seemed drawn to the borderline between theatrical and sexual display. In his “Nighttime on the Boulevard Montmarte” (1885), we are situated in the doorway of a restaurant, looking across the street at one of Paris’s many theaters. There is brightly-lit advertising—presumably for a current show—on the faces of some of the buildings. The electric lights behind us illuminate the street crowd in front of us as if they were on stage. There is a modest amount of litter on the sidewalk; the small tables have empty wine glasses and carafes. A boy is selling newspapers—or perhaps another one of those illustrated magazines–and a woman is negotiating with a waiter. The central figure of the painting is a woman with the sculpted body of the period wearing a hat and muff. There is a man who may have nothing to do with her, or is possibly inspecting her, or possibly following her. She seems to have paused, and is looking over her shoulder. Perhaps she is trying to steal a quick look at the man, for any of several reasons, or is perhaps looking at us, for any of several reasons. Is she frightened by him or does she want to make sure that he is still interested? Does she seek our help or is she startled to find us looking on? Is she indifferent to our gaze, or is she ashamed? It is not clear whether in this painting she is the subject or the object, because the line seems thin and porous. It is modern Paris. There are nothing but eyes and beholders, and people to see. Who is innocent and who is not? Or is it all equally entertaining?

April 2nd, 2019at 10:26 am(#)

Kamholtz has delivered an insightful, comprehensive view of Paris 1900: The City of Entertainment, an important exhibit at The Cincinnati Art Museum. I saw the exhibit three times, the last with my family over the weekend. Stunning and enjoyable.

April 17th, 2019at 12:31 pm(#)

Great article.