Japan, “Kimono”,early 20thcentury, silk, Cincinnati Art Museum; A gift from Eleanor Lee Hart’s collection of Japanese art, 2005.644, Photo by Scott Hisey

As I whipped through “Kimono: Refashioning Contemporary Style” 1 at the Cincinnati Art Museum, several things struck me. First was the aptness of it title, which quite succinctly sums up its basic thesis that the kimono has inspired Western clothing design through its form and surface decoration beginning in the 1870s and continuing to the present. The choice of the word refashioningis particularly delicious.

The second was that I could not think of a garment that was so emblematic of its culture that had had such an influence on Western apparel. For example, the Indian sari has never captured the Western imagination in the same way.

Yohji Yamamoto (b. 1943), Japan, “Dress”, Spring/Summer 1995, silk/rayon blend, polyester/rayon/nylon-blend, © The Kyoto Costume Institute, Photo by Takashi Hatakeyama

In the “Directors’ Forward” 2in the lavishly illustrated book, Kimono Refashioned: Japan’s Impact on International Fashion, which accompanies the exhibition, directors from the participating institutions, divided the show into four sections: late 19th– paintings with subjects dressed in kimono and incorporating Japanese objects; fashion from the late 19thto the middle of the 20thcentury inspired by the motifs, shapes, and cuts of kimono; contemporary fashion exploiting the kimono silhouette and flatness as well as Japanese weaving , dyeing, and surface decoration techniques; and styles informed by today’s pop design in Japan, including anime and manga.

Japan, Kimono, 1850-1900, silk, metallic thread, Cincinnati Art Museum: Gift of Mr. and Mrs. John Emery, 1964.785, Photo by Rob Deslongchamps

The word kimono translates directly as ki, “wearing” on the upper body, and mono, thing. The t-shaped front-wrapping garment with rectangular sleeves originated in China during the Han Dynasty (206 BCE-220 CE). In Japan, there were changes over time–sleeves lengthened, the obi widened, and forms of tying evolved, etc.–but the basic shape remained the same.

It is the textile, how it was woven and decorated, that differentiates kimono.

Japan was a closed society until U. S. Naval Commodore Matthew Perry sailed into Uraga in 1853, ending a period of self-imposed isolationism–sakoku–that began in1633. 3

Although Japan had closed itself off to most international trade during this time, it traded with China and Korea and allowed one European country access: Holland. In the 17thcentury, Dutch traders brought back typical Japanese goods, including padded kimono. They became fashionable among men as housecoats or dressing gowns (rocken)and were accessorized with lace cravats and cuffs and full-bottomed wigs. 4

Once Japan opened itself to international trade, Japanese goods began to flow freely into Europe and were showcased in the popular mid-to-late 19thcentury international exhibitions. This sparked a passion for collecting all things Japanese. Art critic Philippe Burty coined a word for it–Japonism. 5

William Merritt Chase (1849-1916), United States,”Girl in a Japanese Costume”,approx. 1890, oil on canvas, Brooklyn Museum, Gift of Isabella S. Kurtz in memory of Charles M. Kurtz, 86.197.2

European and American painters embraced Japonism as a new theme, sometimes painting their subjects in kimono as a kind of shorthand for exoticism.

Jacques-Joseph James Tissot (1836-1902), France, “YoungWomen Looking at Japanese Articles”,1869, oil on canvas, Cincinnati Art Museum, Gift of Henry M. Goodyear, MD, 1984.217

An early collector of Asian art, Jacques-Joseph James Tissot painted three canvases in 1869 depicting stylish young ladies examining some of his extensive collection. In Young Women Looking at Japanese Articles, they are studying a model of a Japanese trading ship placed on a table covered with a gray kimono. There are also Japanesque screens at the windows, a Persian rug, a blue-and-white ceramic bowl, and a lacquered cabinet displaying kimono-clad dolls.

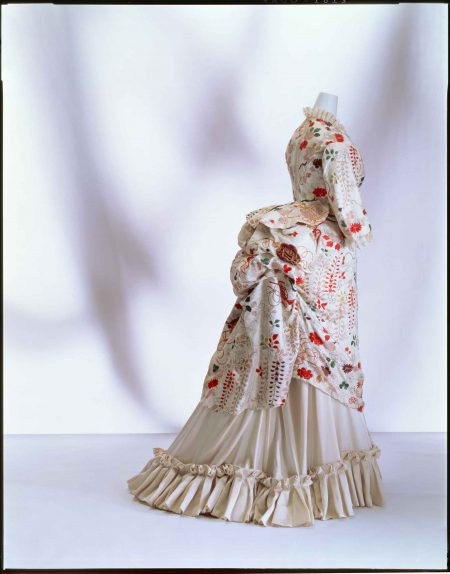

Misses Turner Court Dress Makers (active late 19thcentury), England, London, “Dress”,circa 1875, silk, metallic thread, © The Kyoto Costume Institute, Photo by Richard Haughton

Western designers were taken with the beauty of Japanese textiles. Around 1875the Misses Turner Court Dress Makers took apart a kosode6 to use for the corseted bodice, skirt, and bustle of this fashionable dress.

Misses Turner Court Dress Makers (active late 19thcentury), England, London, Dress(det.),circa 1875, silk, metallic thread, © The Kyoto Costume Institute, Photo by Richard Haughton

Exquisite Japanese textiles inspired the silk weavers of Lyon to produce their own beautiful fabrics. Japanese-inspired patterns became popular in France in the 1920s. 7

Japan, “Kimono and Sash”,circa 1920, silk, Cincinnati Art Museum; Gift in memory of Mrs. William Leo Doepke (Ethel Page) by her granddaughter, Sara Doepke, 2012.95a,b, Photo by Rob Deslongchamps

In the late 19th– and early 20th-century, Western ladies adopted kimono as dressing gowns to be worn in the privacy of their boudoirs or among close family members. With the kimono becoming fashionable, Japanese designers began to produce specifically for the Western market. 8

The loose-fitting kimono was right in line with the mid-19th– to early-20thclothing reform movement that advocated women wear less constrictive clothing. In 1873activist Elizabeth Stuart Phelps wrote, “Burn up the corsets! Make a bonfire of the cruel steel that has lorded it over the contents of the abdomen and thorax for so many years and heave a sigh of relief: for your ’emancipation,’ I assure you, has from this moment begun.” 9

Paul Poiret (1879-1944), France, “Dress”,1920-1030, silk, © The Kyoto Costume Institute, Photo by Masayuki Hayashi

In the post-World War I period that heralded so many changes in society, women became more autonomous. Stylish women rejected the unnatural corseted hourglass figure with exaggerated derrière for body-skimming designs.

Responding to this shift in style, Paul Poiret showed his first dress to be worn without a corset in 1906. The couturier wanted to “create a straight cut and gentle drape in his dresses.” Clothing from several countries and periods inspired him. He was taken by the construction of the kimono, which is composed of rectangular shapes 10 and by ancient Greek clothing that was made from a square or rectangular piece of fabric and pinned together for a quite simple, draped, loose-fitting, and free flowing garment. 11

The illustrated dress, which may have been worn by his wife, Denise, had the illusion of a black wovenhaorior short coat over a gray kimono, but it was all one piece. 12

L. Mayer (1905-31), United States, “Evening Dress”, 1927-1928, silk chiffon and silk crepe, Cincinnati Art Museum, Gift of Dorette Kruse Fleischmann in memory of Julius Fleischmann, 1991.200, Photo by Rob Deslongchamps

American designer E. L. Mayer re-interpreted the kimono silhouette in a silk Evening Dress, with straight lines narrowing at the ankle and long kimono sleeves. The twisted belt might have been inspired by kumihimo, braided cord, or obijime,narrow tie, used to keep a wide obi in place. 13

Contemporary fashion designers have been inspired by the shape, surface design, and construction of kimono.

John Galliano (b. 1960), England, “Ensemble”, Autumn/Winter 1994, wool, acetate, silk, © The Kyoto Art Institute, Photo by Takashi Hatakeyama

The British designer John Galliano offers an amusing take on the traditional kimono form with his 1994 micro-mini Ensemble with a kimono-style collar, wide sleeves, obi-like belt, and train. The kimono has come a long way since retiring ladies wore it in the 19thcentury.

Woven, dyed, embroidered, appliquéd, or beaded, typical Japanese motifs have found their way into Western fashion.

Alessandro dell’Acqua (b. 1962), Italy, for Rochas, Coat, Autumn/Winter 2015, wool, silk, beads, ©The Kyoto Costume Institute, Photo by Takashi Hatakeyama

Around 1890 typical Japanese motifs such as chrysanthemums, irises, sheaves of rice, flowing water, splashing waves, and sparrows began to appear on the Paris fashion scene.” 14

Velvet appliqués of a flock of swallows swoop over the surface of a blue wool-and-silk twill coat designed by Alessandro dell’Acqua for the 90thanniversary of the Rochas fashion house. It references the surface design of a 1934 dress by Marcel Rochas.

Toshiko Yamawaki (1887-1960), Japan, “Dress”,1956, silk, gold, Gift from Yamawaki Fashion Art College, © The Kyoto Costume Institute, Photo by Takashi Hatakeyama

Toshiko Yamawaki uses a simple Western-style dress as the canvas for a dramatic stylized wave, reminiscent of Katsushika Hokusai’s well-known print The Great Wave.

Toshiko Yamawaki (1887-1960), Japan, “Dress: (det.),1956, silk, gold, Gift from Yamawaki Fashion Art College, © The Kyoto Costume Institute, Photo by Takashi Hatakeyama

Yamawaki’s cresting wave is embroidered with gold metallic threads that are held in place with a couching stitch. The back features a fan-shape that alludes to the traditionalobi.

Yusuke Takashi (b. 1985), Japan, for Issey Miyake Men, “Jacket, Trousers, and Shoes”, Spring/Summer 2014, wool, polyester/polyurethane blend, suede, © The Kyoto Costume Institute, Photo by Takashi Hatakeyama

Shibori is essentially tie-dying (yes, like those t-shirts of yore), but it has a noble history that dates to the 8th century. In this process, fabric is bound, stitched, folded, twisted, orcompressed, and then dyed. What has been bound is untouched by the dye and remains the original color of the fabric.

There are myriad shibori techniques. Yusuke Takashi’s, Jacket, Trousers, and Sneakersuses itajime shibori,a traditional board-clamp-resist technique. Fabric is folded and clamped between wood blocks leaving certain areas undyed. They were then hand printed with blue and red blocks for this suit. 15

Issey Miyake (b. 1938), Japan, “Rhythm Pleats Dress”,1990, polyester, linen, Cincinnati Art Museum, Museum Purchase with funds provided by Friends of Fashion, 2007.109 (on mannequin)

Issey Miyake found inspiration in the simplicity of kimono construction. At its most basic, a kimono takes only four panels. Miyake has reduced it further, using just a single piece of cloth: “A-POC.”

Issey Miyake (b. 1938), Japan, “Rhythm Pleats Dress”,1990, polyester, linen, Cincinnati Art Museum, Museum Purchase with funds provided by Friends of Fashion, 2007.109 (flat)

His designs using his signature pleated fabric only take form when worn.

Jean-Charles de Castelbajac (b. 1949), France, Coat, Spring/Summer 1996, silk, ©The Kyoto Costume Institute, Photo by Takashi Hatakeyama

Just as traditional Japanese symbols and motifs have inspired Western designers, two new Japanese expressions of pop culture–manga and anime–have found their way into fashion design worldwide.

In Japan anime encompasses all animation. As a style it’s “often characterized by colorful graphics, vibrant characters, and fantastical themes.”16

Manga refers to both comics and cartooning. Its stylistic roots can be found in ukiyo-e woodblock prints and “kibyōshi (yellow-covered illustrated storybooks for adults).” 17

Jean-Charles de Castelbajac uses the traditional kimono shape as the canvas for three Japanese ladies lifted straight out of a circa 1795 color woodcut by Kitagawa Utamaro (1754-1806) called Three Modern Beauties. He’s added a cartoonish portrait of himself and his dog upside down, as if suggesting the topsy-turvy world we live in.

East has met West as Japan has shared its rich cultural traditions with Western designers who have avidly adopted archetypally Japanese forms, surface design, and techniques.

–Karen S. Chambers

“Kimono: Refashioning Contemporary Style” through September 15, 2019. Cincinnati Art Museum, 953 Eden Park Drive, Cincinnati, OH 45202, phone: 513-721-2787, www.cincinnatiartmuseum.org. Tues.-Sun., 11 am-5 pm; Thurs., 11 am-8 pm. Members, free; general public, $10; seniors, college students, ages 6-17, $5; under five, free

END NOTES

1 “Kimono: Refashioning Contemporary Style” was initiated by Akiko Fukai of the Kyoto Costume Institute in Japan and organized by her institution and the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco. It was jointly curated by Rie Nii, Kyoto Costume Institute; Yuki Morishima and Karin Grace Oen, Asian Art Museum, San Francisco; Katherine Anne Paul, Newark Art Museum, New Jersey; and Cynthia Amnéus, CAM. All were contributors to the lavishly illustrated book–Kimono Refashioned: Japan’s Impact on International Fashion–accompanying the show.

The Cincinnati Art Museum supplemented the exhibition by showing more than 15 examples of traditional and contemporary fashion, paintings, works on paper, and Rookwood pottery from its permanent collection.

2 Jay Xu, director, Asian Art Museum of San Francisco; Yoshikata Tsukamoto, chairman, The Kyoto Costume Institute; Ulysses G. Dietz, interim co-director, Newark Museum; and Cameron Kitchin, Louis and Louise Dieterle director, Cincinnati Art Museum

3 “During the Sakoku period, Japan was not totally closed to international trade after the seclusion edict of 1636, but it was highly regulated. Trading continued with China, Korea, and the Dutch. It was believed that the Tokugawa shogunate imposed the strictures to limit colonial and religious influence of other nations, but the shogunate also wanted to control Japan’s foreign policy to ensure peace and cement its supremacy over other powerful lords.” “Sakoku,” Wikipedia.

4 Cynthia Amnéus, “Wearing Japonism,” Kimono Refashioned: Japan’s Impact on International Fashion, 2018, San Francisco, Asian Art Museum, p.11

5 “Japonism,” Wikipedia

6AnEdo-period garment worn by “elite women of the Japanese military aristocracy. Naoko Tsutsui, “Japonism in Fashion,” Kimono Refashioned: Japan’s Impact on International Fashion, (San Francisco: Asian Art Museum, 2018), p. 48

7Étoffes Japonaises tisséss et brochées (Japanese Woven and Brocaded Fabricswas published in 1910. It featured color reproductions of Japanese textiles from the 17thto 19thcenturies. In 1913 J. Claude company put together a book of samples of silk fabrics woven in France between July 6, 1912, to August 7, 1913. The swatch in the exhibition was included in this book. Ibid., p. 56

8Harper’s Bazaarin 1893 published an “advertisement for ‘Japanese Kimono or Native Dresses’ to be worn as tea gowns or morning wrappers, accessorized with an ‘embroidered and fringed obi or sash,’ made especially for the New York-based A. A. Valentine & Co….” Elizabeth Allen advertised “Hand Embroidered Silk Negligees” for $6.75. For women who couldn’t afford the readymade kimono,Harper’s Bazaar offered tissue-paper sewing patterns. Cynthia Amnéus, “Wearing Japonism,” Kimono Refashioned: Japan’s Impact on International Fashion, (San Francisco: Asian Art Museum, 2018), p. 13

9Carey Dunn, Fast Company,blog

10 Ibid., p. 64

11 “Ancient Greek Clothing,” Wikipedia

12 Moe Sato, “Japonism,” Kimono Refashioned: Japan’s Impact on International Fashion, p. 64

13 Exhibition label

14 Naoko Tsutsui, “Kimono in Contemporary Fashion,” Kimono Refashioned: Japan’s Impact on International Fashion, p. 97

15 Sato, Ibid., p. 88

16 “Anime,” Wikipedia