In the exhibition “Dress Up, Speak Up: Regalia & Resistance”, 21C Chief Curator Alice Gray Stites assembles an impressive group of international artists whose work subverts, reinterprets, and reframes representations of cultural power, communal dignity, and personal agency through costume and its context.

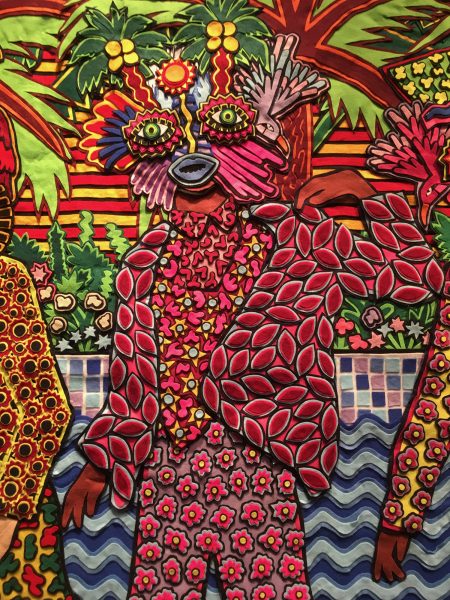

Dress Up, Speak Up gallery view featuring “Brella Krew”, from the Fambily Series, Ebony G. Patterson (left); Soundsuit, 2007, Nick Cave (center); “Find Your Gaggle”, Jody Paulsen (right)

Photo credit: Courtesy of 21C Museum Hotels

While regalia is a familiar term, indicating a formal outfit or ornament worn during an important ritual or event, such as military uniforms and medals worn by generals in parades, the iconic gowns and tasseled caps used for graduation ceremonies, or richly colored robes and headpieces worn by Catholic bishops, it is more than just ceremonial fashion. It is the symbol of power or authority inherent in the person privileged to inhabit that particular attire. In this exhibition, dress is the means by which these artists claim power and authority, both for their subjects and their work.

The meaning of regalia evolved from the Latin “regalis”, meaning regal or royal, to “regalia”, meaning royal privilege and later, royal power.[i] Sumptuary laws in many different cultures, from early Greeks to feudal Japanese rulers, limited consumption of certain goods, including fine fabrics, rare colors, patterns and clothing styles, to certain classes of people, making societal hierarchies easily visible based on what community members wore. Often these restrictions were applied to commoners, to keep rising bourgeoisie “in their station”, or to segregate groups to limit their ability to threaten the ruling order.[ii] Since commoners did not have the power to change laws, resistance against these oppressive strictures came in the form of what they dared to wear.

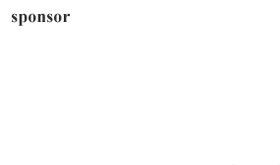

“Proposed Model of Francois Benga” (1906-1957) by Athi-Patra Ruga

Photo credit: Courtesy of 21C Museum Hotels

“Dress Up, Speak Up” on its surface appears celebratory: visitors are surrounded by the human form in two and three dimensions, colorful, bejeweled, boldly gesturing or assembled in vivid tableaux. But this exhibition is full of subtlety and depth in material, process and content, and as the wall labels reveal, each work is inspired by historical and current oppression, violence, or marginalization. The first work that greets visitors, Proposed Model of Francois Benga (1906-1957) by Athi-Patra Ruga, is a memorial to an early 20th century dancer and icon of queer culture in Paris and New York who was disinherited by his Senegalese family and after his death, largely forgotten. Rediscovered for a new generation, Benga’s arm are head are raised up in an elegant arc, his body densely and tenderly covered with crystals and artificial flowers. Jeffrey Gibson, a Native American artist, claims his Cherokee and Choctaw heritage in presenting regalia of his culture while redefining its materials and motives. In Prism, he adds a new layer of meaning to the traditional garment of the Ghost Dance, a 19th century ritual of resistance to white domination. He creates his garment in reference to queer club culture using contemporary fabrics and a bright array of colors. His two headpieces, The Anthropophagic Effect Helmet no. 1 and no. 3 adapt the process of Southeastern river cane basket weaving to craft the forms of ornamental, expressionistic helmets. Though they offer only symbolic protection as armor, they carry the traditional craft into the present. Renowned artist Nick Cave’s Soundsuit, 2007, a delicately colored costume also for resistance-dancing, constructed of found beaded and sequined garments, was inspired by the 1991 beating of Rodney King.

Several works situate new protagonists in archetypal contexts of a dominant culture as a way to critique coded systems of visual representation and assert the presence of people typically ignored or altogether erased from that history. Danish artist Jeannette Ehlers’ 2009 video Black Magic at the White House comments on complicity with the transatlantic slave trade in Europe by performing a voodoo dance in the white mansion of a Danish sea merchant who profited from the transport and sale of slaves. Given the time of the work, it may also reference the election of Barack Obama to the US presidency. In Jefferson Pinder’s performance-video Afro-Cosmonaut/Alien (White Noise), the artist covers himself in white paint and, by standing in front of a projection, inserts himself into the iconic video of the US moon rocket launch, among other images of space flight. During his “journey”, the artist moves gracefully and violently to match the light and action of the rocket and responds to the explosive engines with facial gestures of extreme agony. Pinder’s ghostly figure is riveting as it integrates with flames, clouds and rocket trails in impossible perspectives, accompanied by a sparse, distant soundtrack that includes Dr. Martin Luther King’s “I’ve Been to the Mountaintop” speech. Kehinde Wiley’s paintings incite a state of cognitive dissonance, with their background tapestries visibly weaving contemporary young African American, (mostly) male subjects into the tradition of European Old Master portraiture. Wiley positions his subjects as regal, towering figures of power and importance, confronting the viewer without trepidation. The nearly monumental scale Morpheus replaces Manet’s Olympia, or Titian’s Venus of Urbino with a seductive young man surrounded by flowers who emanates a self-possession of both softness in his posture and gaze, and strength in his muscular body.

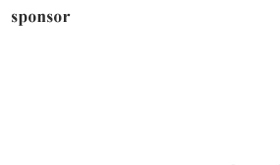

“Portrait of a Woman Without a Basket of Spindles”, Carlos Gamez de Francisco

Photo credit: Courtesy of 21C Museum Hotels

Photography figures prominently in the exhibition as a means to recast cultural narratives. In Dorian Gray, British artist Yinka Shonibare CBE uses photographic film stills to reframe Oscar Wilde’s novel “The Picture of Dorian Gray” as portrayed in the 1945 Hollywood film adaptation. In the stills, Shonibare plays Gray, elegant in 1890’s Victorian formal wear throughout the noir-style black and white images. By layering mediums of literature, film, fashion and still photography, Shonibare investigates the concept of race, class, beauty, and youth across time and multiple art forms. Carlos Gamez de Francisco’s images Portrait of a Woman Without a Basket of Spindles and Historical Speculation portray, with stunning light and rich color, the dignity and beauty of impoverished Cubans draped in everyday materials from their homes such as curtains and towels, in response to portraits of powerful, wealthy patrons in Renaissance paintings wearing their finest clothing. Vivek Vilasini’s Last Supper-Gaza recreates Leonardo Da Vinci’s well-known fresco reimagined as a panoramic image with Palestinian women in hijabs.

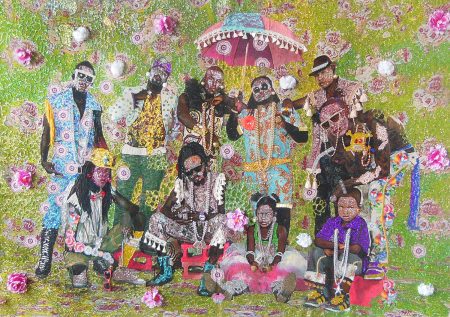

“Brella Krew”, from the Fambily Series Ebony G. Patterson

Photo credit: Courtesy of 21C Museum Hotels

“Brella Krew”, from the Fambily Series Ebony G. Patterson

Photo credit: Courtesy of 21C Museum Hotels

Several artists incorporate non-traditional materials into their works, itself a form of resistance to prevailing artworld conventions. Titus Kaphar’s otherwise traditional oil painting An Icon for Destiny includes the use of tar to render the dark silhouette of a female figure, her features indistinguishable amid the swirls of thick black tar, though her body is surrounded by gold drapery painted with fully dimensional folds. The painting speaks to the absence of representations of black women as a symptom of, as the artist says, “general negligence of society at large”. In contrast, Ebony G. Patterson’s hand embellished photo tapestries accentuate every possible detail of her subjects with sequins, glitter, beads, and metallic fabric. Her work Brella Krew subverts the tradition of European tapestries and classical court paintings with the application of overwhelming bling, while also reimagining the masculinity of Jamaican dance hall culture by feminizing the groups of male figures with flowers and sparkling ornamentation. While Kaphar’s subject’s skin is obscured by tar, Patterson’s subjects’ faces are obscured by silver sequins, a reference to the practice of skin bleaching by ex-convicts to evade facial recognition technology. Even as the power of the figures is reinforced by their presence in the artwork, their identity, their claim to authority, continues to be erased, negated as a result of oppressive structures. Jody Paulsen’s Find Your Gaggle, appropriately positioned adjacent to Brella Krew, is another dazzlingly detailed tapestry, this time constructed completely with crafters felt. Flat vibrant colors in layer upon layer of cut outs assemble to portray a fantasy world of six characters where one’s inner self is freely expressed in outward appearance.

In “Dress Up, Speak Up”, the source and spirit of resistance in each work varies greatly, responding to such issues as the oppression of poverty, cultural appropriation and consumerism, the prevalence of cultural stereotypes, police brutality, homophobia, and government dishonesty, to name a few. The works on display, many more than it is possible to mention here, cover a lot of conceptual ground and provide exquisite examples of unconventional materials and techniques.

–Susan Byrnes

[i] Oxford Online Dictionary

[ii] Brittanica.com