The Women’s Art Gallery at the Greater Cincinnati YWCA ends the year with “A Celebration of Life,” which was co-curated by Ricci Michaels, Urban Expression 101 Project, and Ena Nearon, Women’s Art Gallery manager. The show features the work of seven visual artists and one poet: Erika Nj Allen, Guatemala; Monica Andino, Honduras; Hei-Kyung Byun, Korea; Radha Lakshmi, India; Madeline Ndambakuwa, Zimbabwe; Yudith Vargas Riveron, Cuba; Evelyn Sosa Rojas, Cuba; and Adriana Prieto Quintero, Venezuela. What ties them together is that are all immigrants.

I can rant all day long that we must approach artwork from an aesthetic perspective, but here biography is at the center of “A Celebration of Life.”

Co-curator and Women’s Art Gallery Manager Ena Nearon in front of a wooden Dogon fertility figure from Mali

Nearon writes in the Exhibit Statement:

The experience of being an immigrant entails many levels of cultural adjustment. That often includes language, food, clothing, music, art, and even daily family life. In all areas, there is a melding of former lives with the existing culture in the hope of creating a day-by-day existence that continues the basic value of each person and those they hold dear.

As a whole the exhibition doesn’t quite hang together, but maybe that’s the point. An immigrant herself, Bermuda via a New York Jewish enclave, Nearon sees the Gallery’s mission as being a showcase for a mix of mediums and skill levels, while also presenting “quality art.”

In “A Celebration of Life,” there were two artists who didn’t hit that mark in my opinion: Madeline Ndambakuwa from Zimbabwe and Hei-Kyung Byun from Korea.

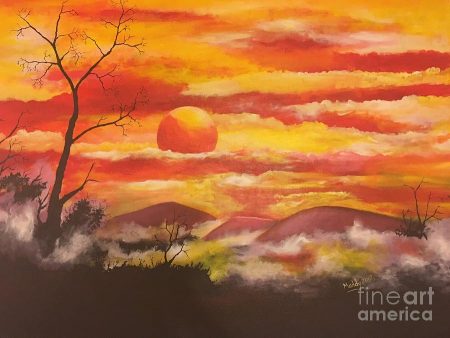

Ndambakuwa was born in Salisbury, Rhodesia, before it became Zimbabwe. She studied Fashion and Cutting Design in Africa and worked as a textile designer there for 11 years before coming to America to pursue studies in fine art. She attended the Cincinnati Art Academy among other schools. Nearon suggests that she is capturing “the ‘bigness of South Africa, the vividness of tribal homes.” Ndambakuwa’s stylized landscape Passion approaches that. It stands out against her overly bright acrylic abstractions that lack compositional coherence and didn’t hold my attention.

Korean Hei-Kyung Byun’s modestly scaled, cast-stone sculptures owe much to Western art. Serenity might have slipped nearly unnoticed into Degas’s studio, and the neo-classicism of Quiet Grace reminded me of Lorado Taft. To Nearon the artist’s adoption of the Western aesthetic marks her transition from the subservient role of women in Korea to “the acceptance of herself in a broader life context” here. I don’t think that message comes across; the sculptures still look derivative.

Guatemalan Erika Nj Allen violated the unspoken rule that artists should stick to a single vision when exhibiting. Don’t make it a multiple-choice quiz of styles. Allen presented brightly colored, rather naïve ceramic sculptures of fruit that Nearon interpreted as a commentary on the differences between her homeland’s and her adopted country’s understanding of what it means to be a woman; the work was sparked by having a hysterectomy, which diminished her femininity in Ecuador. Fruit reappears in spare black-and-white still lifes accented by colorful abstract, but distracting and superfluous, shapes.

Allen goes off in a different–and more successful–direction in her ironically named “Body Movement” series of black-and-white photographs, ironic because her models are not in motion. In Body Movement #1 and #2 (and I hope for more), she photographed the bare backs of two quite skinny (yes, I mean skinny) women. In Body Movement #2, the woman, wearing a floral skirt low on her hips, has pulled her shoulder blades back like wings and holds her arms akimbo with her elbows as sharp as her shoulder blades, a disturbing but powerful pose.

Originally from India, Radha Lakshmi has played an active role in Cincinnati’s fine arts community for many years. She holds a BFA from the Cincinnati Art Academy and currently teaches “Creating Sacred Spaces” workshops for children and adults.

Lakshmi has been influenced by the art of the Northern Territory of Australia, traditional and contemporary printmaking, and the folklore of Chennai in Southern India where she grew up.

A frequent motif for Lakshmi is the mandala, which means circle or point or dot in Sanskrit. It appears in Hindu, Buddhist, Jain, and Shinto religions. To the secular mind, the mandala represents the cosmos metaphysically or symbolically. Lakshmi shows two hand-painted serigraphs: Spiritual Awakening Mandala and Tree of Life Mandala that are vibrant, energetic, and joyful.

Living in Havana, Evelyn Sosa Rojas works in the tradition of documentary portrait photography, probably best exemplified by the work done by Walker Evans and Dorothea Lange for the Farm Security Administration during the Great Depression. Sosa Rojas’s models are always ladies typical of Havana society.

In the October 2019 issue of aeqai, photographer Kent Krugh wrote:

Evelyn’s work is fresh and graceful while irreverent, always focused on the details of the face, gestures, attitudes, and in other small references that become essential in the defining identity. Her portraits are just that: sketches of isolated identities that refer to the diversity of characters in the world.

Sosa Rojas’s black-and-white Diana is an arresting image, reminiscent of Robert Frank’s blunt style. Presumably photographed on a Havana street, Diana is a sultry and somewhat sulky brunette with sensuous lips, heavy eyebrows, and a thick curtain of bangs. I imagine her starring in an Italian film of the 1950s.

Yudith Vargas Riveron lives in Cuba but spends time in the United States. A street photographer by inclination, she elevates the uncelebrated into something of note: the rough hands of a fisherman seen from above cleaning a fish in the color La Cena, the meal, or an anonymous black kid with a basketball on a sidewalk in OTR.

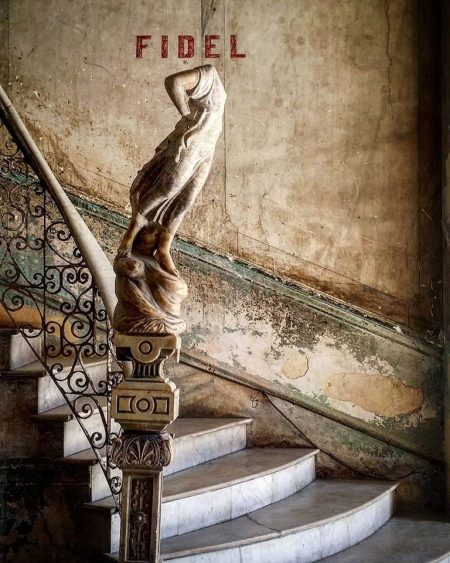

In Fidel, Vargas Riveron’s washed-out color view of a staircase recalls a grander time before Castro came to power. Now the walls have cracked and are peeling paint. As the stair sweeps downward, the railing’s metal scrollwork becomes a graphic element. At the bottom of the stair is a pillar/pedestal for a headless neo-classical statue of a girl; her hands, clasped behind her back, she strains forward like a figurehead on the prow of a ship. The impression is that of the Winged Nike of Samothrace dominating the Daru staircase at the Louvre.

Given my prejudice against visual art that must be (literally) read, I was won over by Any Heaven As A Shelter. The collage is a collaboration by the Cuban illustrator Monica Andino and the Venezuelan poet Adriana Prieto Quintero, remembering losing their homes. Prieto Quintero’s words are written on small strips of paper pasted next to Andino’s charming naïve drawings, some sketched directly on the paper and some pasted on. The simple language of the poem aligns with the childlike images but is quite profound.

BECAUSE I’VE LOST MY HOUSE I THINK OF WHAT IT IS LIKE TO HAVE A HOME. I THINK ABOUT THOSE WHO DO NOT ABANDON THE DESIRE TO HAVE A PLACE TO SPEND THE NIGHT. . ..I THINK OF THOSE WHO WILL NOT BE WELCOMED. EVER ANYWHERE. . ..NOW I FIND A TREE THAT GIVES SHADE. CLEAR WATER THAT REFRESHES. A LONG EMBRACE. THE EYES OF A FRIEND. ANY HEAVEN AS A SHELTER.

Complementing “A Celebration of Life” are five wooden sculptures/artifacts from Africa borrowed from Keletigui African Art. They may be a century old, making them rare because of how quickly wood disintegrates. Depicting queens, fertility goddesses, and shamans, they proclaim the fierce power of women.

I think the exhibition title was a good choice. It’s vague enough to embrace a wide range of work. Unfortunately, it leaves the viewer clueless about the very thesis of the show. We learn personal stories but nothing about immigration writ large. It’s a missed opportunity.

–Karen S. Chambers

“A Celebration of Life” through January 10, 2020, at the YWCA Greater Cincinnati Women’s Art Gallery, second floor, 898 Walnut St., Cincinnati, OH 45202; 513-241-7090, fax: 513-241-7231, info@ywcacin.org, ywcacin.org. Hours: Monday-Friday, 9-5 pm.