Currently on view at LA Louver, Ed and Nancy Kienholz’ playfully eerie mixed-media tableau, The Merry-Go-World or Begat by Chance and the Wonder Horse Trigger (1988-92), evokes the feeling of exploring an abandoned carnival. It’s as though the clowns have departed, the crowds have disappeared, and the games have been packed up; but for some strange reason this Frankensteinian carousel remains. Even stranger, the bodies of its adorning animals bespeak ailment and destruction: a quadriplegic giraffe is propped up on crutches instead of legs; a lion wears a bullet-filled bandolier; a hot pink elephant’s trunk is replaced by a metal air duct; a simian’s face is contorted in a perpetual scream; a glassy-eyed tiger bares its teeth in a ferocious snarl, its bedraggled corpus bisected by a hoop as though it had mummified mid-trick.

Detail, Edward & Nancy Reddin Kienholz, “The Merry-Go-World or Begat By Chance and the Wonder Horse Trigger,” 1988-1992. Mixed media tableau, 115 x 184 in. (All images © Estate of Nancy Reddin Kienholz, courtesy of L.A. Louver, Venice, CA.)

Detail, Edward & Nancy Reddin Kienholz, “The Merry-Go-World or Begat By Chance and the Wonder Horse Trigger,” 1988-1992. Mixed media tableau, 115 x 184 in.

Rather than ride these forbidding animals, you are encouraged to step inside a room among them. “Whoa! One Person at A Time,” declares a sign doubling as a door, daring you to closet yourself alone and discover the secrets within the not-so-merry-go-round’s innermost darkness. First, you must spin a “wheel of fortune” to determine your “chance of birth.” As the numbered wheel shuffles to a stop between one and eight, calliope melodies lilt, bulbs twinkle, and you’re given the green light to enter.

Installation view of “Edward and Nancy Kienholz: The Merry-Go-World or Begat by Chance and the Wonder Horse Trigger (1988-92)” at LA Louver.

Standing at the center of the dark cloister induces a shivery feeling. Spotlights play about you, their beams finally halting at one of eight vignettes randomly selected as your symbolic identity. Will you be reborn as Dwowd, a Bombay barber; Methenge, a Masaai headman in Kenya; Angel, an Oglala Sioux child? Or might you be lucky enough to be Elle, a rich Parisian woman?

The simple arrangement underscores how much of our destinies are determined by conditions out of our control. Any given person could just as easily have been born into the circumstances of another; yet geography, physical features, and economic class are perennial sources of prejudice.

Nancy Reddin Kienholz (1943-2019) conceived of this piece when reflecting on her own biases. She had been born into relative affluence—the “Wonder Horse Trigger” in the title refers to the fact that her parents owned Roy Rogers’ famous horse, “Trigger”—and by the time she married Ed Kienholz (1927-1994) in 1972, he was already a successful artist. On a trip to Juárez in 1983, she willingly gave money to beggar children; but disgustedly refused to give any to a disheveled crone in need. Afterward, she regretted having spurned the old woman; and haunted by her memory of the incident, desired to create an artwork illustrating how one’s fate is shaped by “the accident of one’s birth.”

Upon devising the fortune-telling carousel, the Kienholzes traveled around the U.S. and far-flung lands gathering source material such as photographs and trinkets to use in The Merry-Go-World and its complementary tableaux. Most of the characters are based on real people whom they met on those journeys. To reflect world economic conditions, one character is wealthy, two are middle-class, and five are “poor or extremely poor.”

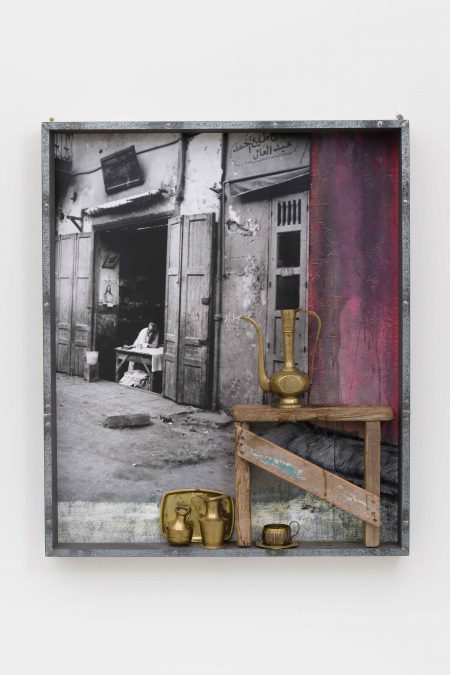

A series of smaller wall-hung assemblages brings out the lifestyles and locales of the people represented inside the carousel. In these, flat photographs are accented by textures and foregrounded by 3D items conveying impressions of specific places. Prototype for Abu-Ben # 3 (1991) transports you to an Egyptian alley where you spy a man, perhaps a shopkeeper, staring abstractedly outside a door as if lost in thought. Real vases on a ramshackle wooden shelf complete the feeling of actually being there.

Edward & Nancy Reddin Kienholz, “Prototype for Abu-Ben #3,” 1991. Mixed media assemblage, 44 x 37 x 4 in.

This exhibition is the first showing of the Merry-Go-World in Los Angeles since it debuted at LA Louver in 1992. According to the catalog, gallery owner Peter Goulds persuaded Nancy Kienholz to allow him to show it again based on its continued relevance. Indeed, its message of empathy seems as apropos as it must have 27 years ago. Economic disparities are stark; people are increasingly intolerant; and various fields’ expanding barriers to entry mean that natal circumstances shape one’s fortune more than ever.

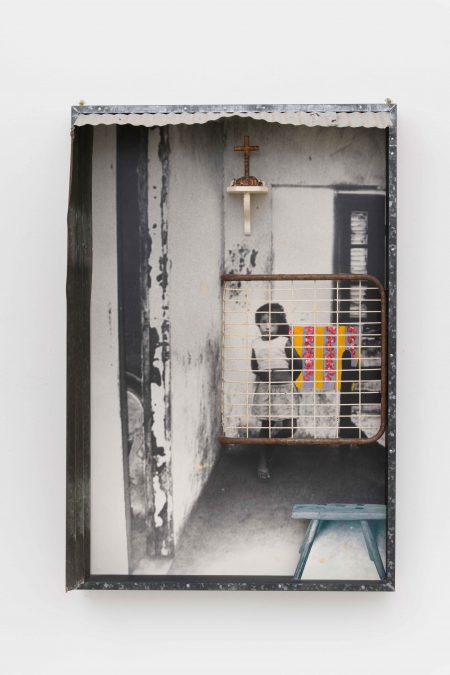

Edward & Nancy Reddin Kienholz, “Prototype for Carmen #1,” 1991. Mixed media assemblage, 48 x 32 x 9 1/2 in.

Sartre suggested that individuals can transcend their “facticity,” or the fundamental conditions over which they have no control, by asserting their own power to think and act within these constraints. “It is therefore senseless to think of complaining since nothing foreign has decided what we feel, what we live, or what we are,” he stated. The artists would likely have agreed. However humble their circumstances, Kienholz’ characters are presented not to be pitied, but to be understood. Unlike the hapless animals on the carousel’s exterior, the human protagonists of the Merry-Go-World and its surrounding assemblages have a degree of instrumentality. Theirs are not the stories of victims, but of people making the best of their situations. A craftsman in Egypt, for instance, taught Nancy how to make chairs should she ever need another occupation. One could spend hours reading the artists’ anecdotal back-stories in the catalog and other materials; but it isn’t necessary to in order to appreciate the work. In Prototype for Carmen #1 (1991), a sober little girl they met in favela stands soberly behind a piece of metal meshwork. Her eyes are barely visible, yet her gaze pierces beyond time and place.