There are a number of roles behind the scenes at a museum that make the place run. One such job is that of a registrar. This article details the life of a registrar at the Cincinnati Museum Center, the Cincinnati Art Museum and the Taft Museum of Art.

A museum registrar manages an art collection, which includes managing the logistics of moving artwork, documenting each art piece and preparing an art collection for display. Museum registrars must have a keen eye for detail to note the condition of each art piece displayed in the museum. Information and data management is also vital. The duties and responsibilities of this job include coordinating art shipments, managing incoming and outgoing logistics, overseeing international customs clearance, directing the installation of artwork and scheduling art exhibitions.

First on my list to talk to was Maat Manninen, registrar, at the Cincinnati Museum Center. He described his job, “It is so varied. It sounds dry and clerical, but it’s an amazingly diverse role.” He noted it changes from museum to museum with the size and type of collection.

At the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, for example, there is a separate registrar doing different kinds of functions. Manninen said his role is a solo job, but he works with a lot of other people, exhibitors, planners, and curators.

His background is a bachelor’s degree in art history from the University of Cincinnati with a master’s degree in art education from the Art Academy of Cincinnati in 2002. He moved out-of-town to become a preparator at the Albuquerque Museum, New Mexico. From there, he went to the Worcester Art Museum from 2008 to 2017. Realizing he had missed Cincinnati, he returned in 2017 to become registrar at the Cincinnati Museum Center. His first day was the closing of the Star Wars exhibit.

“It has been a crazy ride,” he said. There was the renovation of two years ago. He works at the Geier Research Center, Gest & W. 5th Streets where a majority of the collection is located. “We lost storage capacity in the renovation,” Manninen said. Now, “we lease space in a facility in the area.”

Manninen maintains records, history, objects and fine arts of the collection in paper files and in a database in his role. He has a new acquisition meeting every two months. He also deals with loans, insurance and coordinating shipments.

There are two collections from two different museums in Guatemala for the newest exhibit Maya: The Exhibition. It was produced by MuseumsPartner in collaboration with the National Museum of Archaeology and Ethnology (MUNAE) and La Ruta Maya Foundation in Guatemala. Since it was an outside produced exhibit, Manninen spent less time hands-on with this exhibit. He helped with the unpacking, checking off each piece, signing off on condition reports and environmental factors.

Manninen is now heavily involved with two permanent exhibits. He searched through objects that might be suitable for different themes presented, provide photos and dimensions and consulted with the in-house exhibits department regarding mount making and display considerations. He is also responsible for ensuring that objects are displayed according to best practices regarding temperature, relative humidity and light-exposure mitigation.

“Shaping the City” looks at the founding, development and problem solving for the growth of Cincinnati from roughly the late 18th century to the present and beyond through the lens of transportation vis-à-vis rivers, canals, roads, rails population and manufacturing, according to Manninen. For this exhibit, the museum worked with Roto, the design and production firm based in Dublin, Ohio. It also worked with the design/production department of the Science Museum of Minnesota.

The second exhibit is “You Are Here, What It Means To Be a Cincinnatian.” He worked collaboratively to get this up and running.

He was involved in the legwork of shipping, crating, packing and insurance with an exhibit such as Winslow Homer traveling from the Worcester Museum to the Milwaukee Museum – all the details that make a complicated move possible.

He finds most enjoyable working with the objects themselves. And, secondly working with various talented people.

His challenges are project management, not having enough time, loan requests and donations.

He finds the Cincinnati Museum Center unique due to the breadth of its collection from automobiles to fossils to textiles. Keeping a handle on it can be a challenge. Different objects require different conditions.

His impact on the Center is keeping the care and safety of the collection at the forefront. “I’m a wheel greaser,” he said working with the exhibits. He helps facilitate sharing the collections for in-house exhibits, education initiatives, outside institutions and researchers. “This involves an extraordinary amount of collaboration and planning between our curatorial, exhibits, marketing and education teams,” he said.

The Center’s claim to fame is its variety of objects and its unique architectural space, according to Manninen.

“You can come into the role in a number of ways,” Manninen said. “You can’t define every day. It is dynamic, exhausting and stressful, but rewarding” he added.

I next talked to Carola Bell, registrar for loans, Cincinnati Art Museum. She has been there since 2001 with one brief interlude into business. She works with a small team headed by Chief Registrar Jay Pattison. She describes two parts of what the team does – recordkeeping of the artwork and coordinating logistics. There is also dealing with acquisition, loans, exhibitions, shipping, rights and insurance.

Bell mentioned that the role of a registrar may vary depending on the size of the museum. One may specialize in registration and the other may focus on exhibitions. At CAM, “We’re in the middle,” she said. There are six people in the department and are split between the permanent collection and the exhibitions.

Pattison as chief registrar becomes involved in loans. When the museum was asked to loan Monet’s Rocks of Belle-Ile, Port-Domois to the exhibition Claude Monet: The Truth of Nature, it travelled to the Denver Art Museum in Colorado and now is at its final venue, Museum Barberini in Potsdam, Germany. Pattison became involved with the details.

A letter is often sent to the director of the museum with background information, then forwarded to the registrar and routed to other departments such as conservation, curatorial and installation. Questions raised include has it traveled recently and what are the facilities needed? The curator may review its exhibition history. Eventually, the information is forwarded to the director for final approval.

Bell works with the permanent collection, for example, what comes into the building, shipping, packing, installation, managing inventory and a database. Any time a piece of art is moved, it is recorded by the registration department. Deaccessioning is also part of the process.

Assistant Registrar Molly Stark deals with storage, onsite, offsite, monitors space and things like temperature. There are a lot of details that go into this work.

Exhibitions are the second part of the picture. Ideas for an exhibit can come from anywhere. They may come from the director, the curators or others. Proposals are submitted to an Exhibitions Committee represented by various departments including the executive, curatorial, design and installation, registration, marketing, learning and interpretation, and philanthropy.

Ideas go to Susan Hudson, director of collections and exhibitions, for a potential budget and timeline. She works closely with the curators and the finance department. Bell talked about the tremendous effort that goes into any show. There are sometimes exhibits from CAM’s collections. Since exhibitions are expensive, “We do one of our own,” she said.

Elizabeth Williams, curator of decorative arts and design, Rhode Island School of Design originated the idea of the exhibit Gorham Silver: Designing Brilliance 1850 – 1970 four years ago. Two years ago, Amy Miller Dehan, curator of decorative arts and design, became involved. The exhibit was only open a few days when the museum was forced to close due to Coronavirus. There was a great deal of research that went into over 600 objects on display.

Bell, as registrar for loans, makes the request for loans of artwork from other museums and obtains loan agreements. She said, “Lending is one way to share our collection with a broader community. Art truly doesn’t have borders.” Subjects include the condition report of the art, the status of a crate, unpacking each object, security wires, what needs to be planned, maintaining curatorial files, custom coordination of what goes on a plane, working with transfer agents for import/export and courier arrangements.

There are lots of couriers and a lot of scheduling for a large show involving a painter such as Picasso. “We’re fortunate to have enough staff,” said Bell to handle this process. “It’s a very collaborative experience. We have all done the job before and are aware of what needs to happen. We know when to ask for help. It keeps it interesting, for sure,” said Bell.

One of Bell’s favorite parts of her job is traveling. “I have to travel with the artwork. I like to see how other places do things. If I am in the office too long, I get cranky. It’s time for a trip.” Surrealism is of interest to Bell. When she saw a number of works at the Tate in London a few years ago, including an entire gallery of Mark Rothko paintings, she was thrilled.

she often finds ideas she brings home to share with the team on her trips. “Most have to do with interesting art movement tools or installation methods,” she said. “It can be anything, really, maybe a new type of security hook or a crate dolly that also works as a J-bar. In general, preparators everywhere are pretty creative; our team is no different. They are interested in and appreciative of what their colleagues around the world are doing. If the right tool doesn’t exist, they often make what they need.”

The most challenging part of her job is finding better ways to work smarter, not harder. “We have to keep track of it,” she said. “We’re still a nonprofit. It’s hard to get a headcount at CAM,” she added. That said, the numbers of visitors and exhibits are up, all a positive sign.

“It’s the best of both worlds,” Bell said. “I love being around art. Everyone is very creative and inspired. I don’t want to be on the front line.”

The curators and directors have a vision. “We’re making that happen,” said Bell. When she gets frustrated, she tries to take a step back and see what the bigger picture is.

She finds people gracious in the registrar’s role. “You get to share something. None of us can do it alone. You need the art handlers, preparators. It’s a team effort.”

“I lucked into this role in a highly competitive field,” Bell said. “You have to be on top of your game. We’re the museum that could.”

Pattison said, “”I think of us as the eyes and ears of the artwork. Art has a mysterious power to amaze and move us but, as objects in the physical world, works of art need human agents to preserve and catalogue them to ensure they’ll remain accessible. Even conceptual and digital artworks need installation instructions and preservation plans in order to honor the artists’ intent. As registrars, it’s our job to maintain these treasures across time so they can continue to work their magic.”

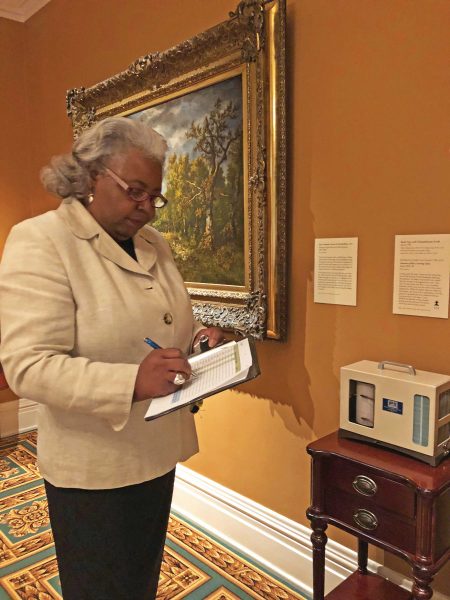

Joan Hendricks, chief registrar and collections manager at the Taft Museum of Art said, “My job is different than that in some other museums (especially larger ones) in that I touch upon all the registration and collections related tasks on a regular basis. We are a small museum and there is a half-time assistant registrar who works with me two days per week. So, that means I get to work on every exhibition and most projects in some form or fashion. This would not be the case in a larger museum.”

The last exhibition Hendricks worked on was the NC Wyeth: New Perspectives. She received the crated exhibition, assisted in condition reporting of paintings, and provided oversight of unpacking and installation of works. The registrar creates the installation schedules with assistance from the chief preparator and exhibition designer.

Hendricks said, “Every work of art that enters the museum for gift or loan purposes is checked with the purpose of documenting its condition. This is done to protect the museum, for insurance purposes, and to assist in determining where damage has likely occurred in the event that something has happened to a work. The Taft does not actively purchase works, but if it did, those would be examined upon entry to the museum as well.”

The registrar is not involved in the selection of objects at the Taft. That said, the registrar is asked to weigh in on the selection of exhibitions that are procured from other outside exhibition organizing institutions regarding logistics.

Hendricks, on the other hand, has extensive input or supervision of the movement of art within the Taft Museum of Art. Objects are not moved without informing the registrar of their movement. Art is supervised for all points of movement from truck to gallery.

Rebecca Roman, registrar, Contemporary Arts Center, declined to be interviewed for this article because of COVID-19.