James VanDerZee (1886-1983) produced somewhere between 75,000 and 100,000 photographs in his creative lifetime, maybe even more, almost all of them of African Americans who lived in or were passing through Harlem. He had a fraught relationship to street photography and worked predominantly out of his studio. At the height of his career in the 1920s and 1930s, he might have had three to four portrait sittings every day. His busiest and most fruitful day was Sunday because, as he once said, “the high class, the middle class, the poorer class all looked good on Sunday,” though it is fair to say that his greatest achievements were his depictions of those whose accomplishments and aspirations were not too distant from the newly prosperous, ambitious, and self-aware African American middle class.

Born and raised in the tiny resort community of Lenox, Massachusetts in the Berkshire Mountains, VanDerZee had his first camera by the time he was a teenager, though his family was generally arts-friendly and he was also given extensive instruction in the piano and the violin; ultimately he sat in sometimes with Fletcher Henderson’s orchestra. By 1906, he began living in and around New York City, where he would stay for the rest of his life, learning the ropes of darkroom work and portraiture, and opening his own studio in Harlem by 1916. Although he was not, like some photographers of his time, a recorder of the modernizing city, being a New Yorker meant a great deal to him: throughout his whole career he signed his prints by scratching his name onto each negative along with the date, and “NYC.” When he takes his “Self-Portrait” in 1918, he presents himself in a straw hat, his sleeves rolled up, a cigar in his hand, reading and pointing with a bit of a sly grin to a headline in an Indianapolis newspaper about Black troops distinguishing themselves in battle. He seems like a neighbor, a story-teller, a local rascal.

Like a lot of photographers directly dependent on customer support, he saw his popularity and prosperity wane with the Depression and the increasing ubiquity of individual camera ownership. He worked when he could and maintained his archives until, his fortunes nearly in ruins, like Atget before him, he got his great break. His work was rediscovered by photographer and researcher Reginald McGhee in the run-up to the Metropolitan Museum’s notorious “Harlem on My Mind” exhibition of 1969. In a show of floor-to-ceiling panels with enlargements of documents and works of art illustrating the history of Harlem’s people and cultures, VanDerZee’s work, according to Susan Cahan, constituted 50 of the 700 works of art reproduced for the show, a larger showing than any other single artist there. One of his pictures was blown up as large as 12 feet by 50 feet. The recognition did not come soon enough to keep him from being evicted from his home and studio, but it marked the beginning of his being positioned as a significant figure in the history of photographic art, leading to portrait commissions, many exhibits, about a half dozen books or free standing catalogues about the man and his work, and his photographs entering public and private collections.

Having photographed some of the celebrities of the Harlem Renaissance in the 20s and 30s, such as poet Countee Cullen, entrepreneur C. J. Walker, dancer Bill Bojangles Robinson, and Cincinnati-born blues singer Mamie Smith, he would live long enough to do portraits of Cicely Tyson, the young painter Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Bill Cosby, in whom he seems to have seen the echo of the vaudevillian figure from decades earlier. But by far, his most revealing, perplexing, and significant photographs are of people we’ve never heard of, posed against painted backdrops, elaborately and impeccably dressed, with an assortment of props close at hand, including vases of flowers, a candlestick telephone, and a painted, cut-out dog. The Metropolitan Museum, whose belated recognition brought him attention and eventual financial security, now owns 66 of VanDerZee’s prints; the Cincinnati Art Museum owns 6, which is a startlingly good showing. Curator Kristin Spangenberg notes that they were all from the collection of Regenia Perry, who was the first African American woman to earn a PhD in Art History. Over the years, Perry assembled a distinguished collection of African American folk art, but also had a special interest in VanDerZee, on whom she wrote a book in 1973. In 2001, the Museum was able to select six vintage prints from different parts of his long career.

What is at stake with VanDerZee’s work? The “Harlem on My Mind” show treated his pictures as documents, but there is something deeply equivocal about them in those terms. What exactly do they document? Our ability to answer that assuredly is complicated by the fact that over the years, his thousands of portraits, which were never intended to be anonymous or “types,” no longer have the actual names of their sitters attached to them. VanDerZee knew his status as documentarian was compromised, even more than that of the usual studio portraitist, by his retouching and various post-production efforts: “I tried to see that every picture was better-looking than the person.” Was he a realist or an idealist? He worked during, recorded, and was part of the great cultural moment known today as the Harlem Renaissance, but that moment was itself complex and deeply divided. Were VanDerZee’s photographs intended to defend African American culture as being equal to white culture or to celebrate it as distinct from it? Why is the extreme artifice of many of his studio shots sometimes familiar and comfortable and sometimes deeply unsettling? As we sort through the issues about individual and cultural identity that his portraits raise, in what ways do they shed light on the subjects of the photographs and in what ways are they about the taker of those photographs?

In some of his earliest surviving photographs, like “Kate and Rachel VanDerZee” taken in Lenox in 1907, he seems at ease with a portraiture that is almost candid. His first wife and daughter have been out in the woods gathering greenery and are pausing before crossing a stream on a wooden plank. VanDerZee’s relationship to the tradition of street photography, virtually invented by Atget, pioneered in the earliest years of the 20th century by artists such as Stieglitz, and destined to be changed forever by the work of such figures as Berenice Abbott and the WPA photographers, was complicated. One of his most iconic images, “Couple, Harlem” (1932), hinges on contrasts between the light and the dark, the softness of the raccoon pelts and the hardness of the metal, the organic flow of their coats and the angular gleam of the great machine. She is standing outside the Cadillac V-16 in the bright but soft light of the street and he is sitting inside the car in the shade. It is a two-seater, not a family vehicle. They’re not that kind of couple. They are together, but not particularly attached to each other in this picture. She is looking in our general direction, but he is looking out from the shadows straight at us. This car is mine. He can think that because he knows it. As Thelma Golden wrote of VanDerZee, he tends to focus on the “economically empowered and the socially engaged.” The man in the car is very sure of himself, and he is challenging us to make something of it. He is not asking permission for anything. He is one version of what Alain Locke called, to use the title of an anthology he edited in 1925, “The New Negro.”

But generally, VanDerZee preferred his street people indoors. In some of his studio work, we see echoes of a pictorialist tradition, where painted backdrops merge with a painterly approach to his subjects. “The Barefoot Prophet” (1929) portrays Elder Clayhorn Martin, a street preacher who stopped wearing shoes when he got the spirit and never wore them again. In VanDerZee’s photograph, which could practically have been taken by Julia Cameron, he is peaceful but intense, absorbing the word of God as he reads the Bible. The energy of his street persona is alluded to, but not put into action, by the tambourine that sits under his chair, a part of his outdoor performance now turned into a studio prop.

The studio was VanDerZee’s comfort zone. The absurdly artificial and constrained space it offered him—a few painted backdrops, some furniture, some two- and three-dimensional props that tend to reappear again and again—became a code for the far more open imaginative space in which his subjects lived, and where the photographer was free to explore his own complex selfhood along with those he took pictures of. The studio could be made to suggest all seasons, a range of socio-economic environments, inward spiritual depth, and outward glitz and glamor. There was nothing literal about it; some indoor scenes have the painted backdrop of a pond behind the characters. It served as his armature upon which other things could be built. Despite—or more likely, because of—its very prosaic nature, the studio became what Alina Cohen has called his “site of fantasy and self-invention.”

In “Untitled [Man with Two Dogs]” (1931), a man whose hat is at a jaunty angle crouches down to be close to his two dogs. (In this picture, the dogs are real; they aren’t always.) Behind him is the painted backdrop of the pond; in an earlier picture, “Eve’s Daughter” (1920), a woman stands in front of the same backdrop, but the photographer has scratched into the negative a few aquatic birds. On the one hand, the man with the two dogs seems a little stiff; on the other hand, he seems kind of cool. He chooses not to tower over his animals and dominate them; it’s just a picture of three close friends. VanDerZee has made him comfortable—not just as a Renaissance portraitist might flirt with his subject to capture that beginning of a shy smile, but because in the subject’s comfort, he can become transformed into something new. Within the limits of his props, his studio, and the visual language he used, he helped his subjects become something of their own choosing.VanDerZee, though fundamentally self-taught, worked out a fair amount of darkroom magic to enrich his studio scenes. He etched on his negatives, inserted text (a funeral picture includes a selection from “Thanatopsis,” William Cullen Bryant’s classic poem on grief written more than a century before), and added by photomontage and double exposure symbols and figures–typically of someone no longer of this world–to suggest the presence of lost persons. In “Daydreams” (c. 1925), a woman dressed in black sits by herself on a doublewide chair. A photograph and a crumpled handkerchief lie on her lap. She is being embraced from behind by the figure of a transparent man while she looks out at us. While it might be a picture of a woman whose imagination can conjure up the loved one from whom she is separated (the backdrop here, suggestively, is the ocean), it is more likely that he is dead and is offering her comfort from beyond; the fact that it could be either is rather suggestive. In “Family Album—Memories” (1938)—one of the six VanDerZees in the CAM collection—a father is surrounded by three children who are looking through a photo album. At his feet is the painted dog. Behind and above him hovers an image of a young woman—a lost wife and mother, I assume. His children are too absorbed by their mourning to notice anything. He looks out directly at us with a stare that is almost a glare. His grief is a layered emotion, though the sentiment is not obscure.

I’m not sure of the logistics of these photographs (where does the living image of the departed one come from?), but the picture raises interesting questions about what sort of audience is envisioned for such images. It is often suggested that many of VanDerZee’s pictures—especially those that mark occasions like weddings or funerals—were designed to be sent to family members, presumably those still down south who were not part of the great African American migration to the cities of the north. But “Family Album” seems less designed for export. Though there is always an appetite and a market for sentiment—whether one’s own or that of others—this seems like a picture whose intended audience is the father, who can see himself both being part of the domestic environment and yet also distanced from it, in a place his children cannot see or appreciate. The complexity of his emotion has been privileged.

The deeply new in VanDerZee’s photographs is often balanced off against the deeply traditional. The “Young Man with a Telephone” (1929) would look, on the face of it, completely familiar to someone whose photographic sensibilities were shaped by the late 19th century portrait card. A young Black man is standing by a table in front of a painted backdrop, this one suggesting more of a country estate; it could belong to the set for a production of The Importance of Being Earnest. It is an interesting part of VanDerZee’s urban sensibility that so many of his studio portraits tend to ruralize their subject matter. The backdrop is unlikely to call to mind even the finest of Harlem dwellings. The whole image is a curious mixture of urban and anti-urban, calling our attention to both the urbanity of middle class African American life and the huge cultural and historical flight from it. There is something a little jittery about the young man—it seems that he is briefly perching rather than being at rest. He is engaged in what a number of the best commentators on VanDerZee call “self-fashioning”; Glenn Jordan notes that for VanDerZee, his studio was “an ideal space within which these subjects could rehearse and perform their new identities.” Our young man wears a three-piece suit and his hand rests on a candlestick telephone, a sign of middle class success since the 1890s. But the table is clearly not a work desk; the photograph has no interest in suggesting the source of his economic comfort. He is dressed for that role and that is that.

It is not just that clothes make the man in VanDerZee’s world, but that costumes make the man. VanDerZee was drawn in particular to extravagant outfits, whether it was women wearing exotic and vaguely eastern layered veils, or the actor in doublet, tights, and cape playing Othello in “Dress Rehearsal—Walter Smith” (1936), plunging a sword into his breast in front of that same backdrop of a pond. An “Unidentified Boy” (1930) wears a top hat, a three-piece suit with a white vest, and brightly shined shoes, and even though he is posed in front of a painted country scene, he is clearly being an urban entertainer. A young woman “Posing at the Beach” (1930) wears a bathing costume while she reclines near some painted dunes and a lowering sky. VanDerZee’s pictures celebrate people who make their own identities, whether provisional or essential. Sometimes these identities can be transgressive, such as the cross-dressing “Beau of the Ball” (1926), which surely enriches our sense of the 1920s. A “Couple in the Snow” (1929) stand side by side in front of a painting of a snow-covered country lane, she wearing a fur-trimmed coat, he with a double-breasted overcoat over pinstripe pants and shoes with spats. It’s not like it doesn’t snow in Harlem. But VanDerZee’s studio functions like Dr. Who’s TARDIS, taking you to where and when you want to be. Though the couple is dressed for warmth, they are clearly not dressed practically for snow on an unshoveled country road. But the picture commemorates the ways that the urban sensibility has colonized the rural one, while still keeping in touch with its rural roots; much of the great migration goes barely one or two generations back at most. The costumes make it clear that this is a visit, not a return; the fantasy is provisional. We know—and the couple knows—where they really belong.

This sort of imagery leads a critic like Louis Siddons to suggest that in part, VanDerZee functions like the trickster figure in African American folklore, and turns his subjects into trickster figures as well. In moments like these, they all both consume and disseminate illusion, the illusion of being two things at once. It is probably fair to connect this to W. E. B. Du Bois’s great and famous comment in The Souls of Black Folk (1903) that race in America is always a matter of “double-consciousness,” and that the Black in America “ever feels his twoness.” Performance is not a disguise, but inseparable from identity itself as the African American negotiated the demands and opportunities of multiple cultures.

In “Riding Habit” (1939), a young woman in jodhpurs and tall boots stands in front of a flower-laced decorative grill (the same one used in “Family Album”). There is an ongoing debate about whether VanDerZee supplied the costumes his sitters wore—as artists have done for centuries, from Rembrandt’s studios to the trunks of exotic outfits in William Merritt Chase’s paintings of his studio–or whether his subjects provided their own. A telling piece of evidence might come from a relatively unposed picture published in a newspaper of a couple walking into VanDerZee’s studio already decked out in their finest. So what are we to make of the woman in the “Riding Habit”? After all, in VanDerZee’s New York, there were public riding stables all over Manhattan (the famous Washington Mews, before being converted to fabulously expensive and photogenic row houses, started off as a line of stables in the 1830s), including “Striver’s Row” in Harlem built in 1892 with stables behind each house. Is this where the young woman in the riding habit belongs, or is it where her fantasies have taken her? The painted dog, ever obedient—completing the image of the Town and Country life—sits faithfully at her feet. Her hands are jammed into her pockets—one senses that VanDerZee found that he had to master the skill of telling people what to do with their hands. She sports a slightly awkward half smile, as if she is only partly at home in this image. We see both woman and role; she seems to be saying, “I can make myself into this.” One does not have to be playing Othello or the child entertainer to be living a fundamentally performative life. One of VanDerZee’s great gifts in his cultural moment was to see the Gatsby in everyone.

It is not hard to see the political implications of many of these images, even when the content is ostensibly about creations of imaginary domesticities. There was a more overtly political side to VanDerZee’s work, as well. It is impossible not to read the historical resonances in “Escape Artist” (1924), a picture of a young black man wearing an open collared white shirt and dark wool pants, who is also festooned with chains around his chest, ankles, hands, and neck. The picture was made very close to the end of the age of Houdini, who lived in a Harlem townhouse a mile and a half from VanDerZee’s studio until his death in 1926. The young man, being or playing at being an escape artist like Houdini, stares expressionlessly directly at the camera. Wearing the uniform of slavery over a more conventional uniform of middle class ease, he seems to be responding to centuries of restraint and enslavement with defiance and, as an escape artist, the powerful conviction that he can get out of this.

VanDerZee’s most overtly political work came during the 1920s when he worked as the staff photographer to Marcus Garvey’s UNIA—the Universal Negro Improvement Association. Founded in 1914, its offices were a two-minute walk down West 135th Street from VanDerZee’s studio. For a decade or more, the UNIA was in competition with the nascent NAACP for the loyalty and imagination of African Americans, with (to simplify enormously) Garvey’s group believing in cultural separatism and a powerful back-to-Africa credo, as opposed to the NAACP’s belief in integration and legal change. VanDerZee’s photographs were published in the UNIA’s weekly newspaper Negro World. I have not had access to anything like the complete archive of VanDerZee’s relationship with the UNIA, but it doesn’t seem surprising that he might have been drawn to Garvey, with his mixture of pragmatism, mysticism, entrepreneurship, and charisma. Besides, during the UNIA parades in Harlem which VanDerZee documented, Garvey tended to wear an elaborate military regalia that would have made good sense to an artist who believed that costumes made the man.

Though VanDerZee was responsible for some of the most iconic pictures we have of Garvey, one of the most telling pictures he took from that world doesn’t have him in it at all. In a picture generally known as “The Man Who Came Back” (1924), there is a swarming street scene with a huge poster in the background for the silent movie directed by Emmett J. Flynn. Focusing on the poster, however, tends to transform the image into an image more like Margaret Bourke-White’s famous photograph of “Louisville Flood Victims,” showing a line of desperate African Americans waiting for food and relief after the 1937 Ohio River Flood, standing in front of a billboard that ironically proclaims “World’s Highest Standard of Living.” VanDerZee’s picture, on the other hand, is likely to be a sheer celebration of the size of the crowd, stretching back almost as far as the eye can see, well dressed, attentive, waiting for the UNIA parade. What matters most is not the central figure, but his audience. In fairness, it must also be noted that the colossal advertisement for the movie shows a man crawling over a globe, so the possibility of irony should not be dismissed too easily.

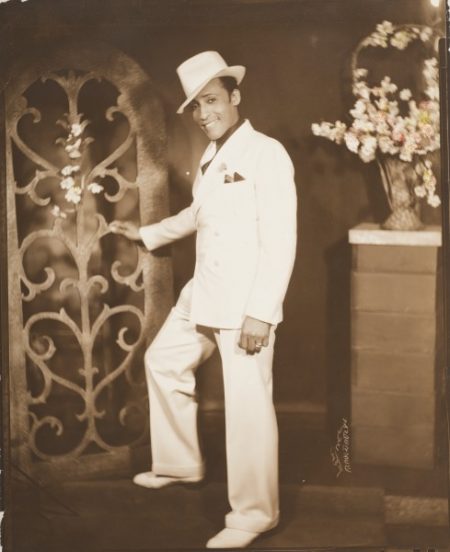

Many of these issues come to a head in what is arguably the greatest of the CAM’s VanDerZee photographs, “Harlem Playboy” (1937). Though it is hard to know with certainty the source of the generic titles that VanDerZee’s images have acquired, the term “playboy” is a surprisingly rich word. Its roots go back to 17th century theater and acting. By the 19th century, it had gradually become a word for a man given over to self-funded leisure and sexual promiscuity. In racial terms, it additionally acquired the suggestion of a man who resisted his disempowerment by acting outside the expectations of the workaday world. In almost every case, it designates the non-domesticated man. VanDerZee’s “Harlem Playboy” is dressed entirely in white except for his shirt and pocket square. What he chiefly wears is a devastating smile: disarming, sly, friendly, open and natural, practiced and mask-like, enticing and not without menace. One foot rests on the floor and the other on a stair. The lattice screen (which we saw before in “Family Album” and “Riding Habit”) here seems more an impersonal decorative accessory, like something one might find in a hotel lobby. As he steps on it, is he exiting or arriving? Is he coming in for you or are you supposed to follow him out?

On the other hand, his image is softened by a vase of flowers on top of a table. The flowers, as frequently happened in VanDerZee’s studio portraits, have been hand colored, giving a loveliness to something in the picture besides the crispness of his suit and the dazzle of his smile. He is also wearing a wedding ring, not an impossible thing in the tradition of playboys, but something that suggests a familiar issue in VanDerZee’s complex enactments. Is he a figure freshly scooped up from the street, or another middle class man with a theatrical bent trying on a costume and a role, as imposing as Walter Smith’s Othello only without the sword and tights? Is he a figure of danger and titillation, or another brilliant middle class impersonation?

And is there really a difference between the two? Perhaps not, if we see VanDerZee’s work as a rich response, whether conscious or not, to Du Bois’s sense of the African American’s double-consciousness, his insight that there is a self-aware role-playing everywhere in Black life? The right question, then, may not be “To which culture do VanDerZee’s subjects belong?” but “How are they depicted as belonging to multiple cultures at once?”

–Jonathan Kamholtz

Note

There is a deep and sumptuous critical and scholarly body of writing about VanDerZee, some of which I have been able to read in full and some of which I have encountered only in excerpts. Among the best I have looked at are Glenn Jordan’s “Re-membering the African American Past” (2011), Louise Siddons’s “African Past or American Present? The Visual Eloquence of James VanDerZee’s ‘Identical Twins’” (2013), and Deborah Willis-Braithwaite’s pioneering VanDerZee, Photographer: 1886-1983 (1993).