The retrospective exhibition “All Things Being Equal” by Hank Willis Thomas has recently opened at the Cincinnati Art Museum. Planning for this highly anticipated show began three years ago, and the timing of its opening was postponed for several weeks due to the Coronavirus pandemic. During those weeks, George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, and Ahmaud Arbery were murdered, and protest marches erupted around the country. Now, Thomas’ work, which illuminates the ongoing struggle against racism, is more relevant than ever.

The first work you encounter in the exhibition is “All Power to All People”, an eight foot, 800 lb. Afro pick. This was made as a prototype public monument and was installed as a temporary work in Fall 2017 in Philadelphia’s Thomas Paine Plaza. It stakes its claim, with long stainless steel rods for teeth, piercing its low plinth. The show is extensive, featuring over 100 works in photography, sculpture, multimedia installation, textiles, and neon. Thomas is also very active in the public realm, making billboards and even co-founding a Super PAC, called “For Freedoms” with a goal to involve more creative people in civic processes. Concurrent with this exhibition, the Art Academy of Cincinnati has hung a banner of the “All Li_es Matter” billboard image Thomas created for a “For Freedoms” project from their building in Over the Rhine.

The art in this exhibition is made in an array of media, but photography is the thread that ties the show together. Its role in the visual representation of Black people is a primary influence in the work of Thomas, known as a conceptual artist. He was introduced to the power of photography by his mother, Deborah Willis, a photographer, photography historian, and MacArthur “Genius” Award recipient whose first book was called “Black Photographers 1840 -1940, A Bio-Bibliography.” In this book Willis brought to light what had not been compiled before: images of Black people made by Black photographers, in some cases long before the Emancipation Proclamation. Many early images of Black people made by white photographers depicted them as unflattering or clownish caricatures, but Willis’ book upset that cultural narrative. The photographer Augustus Washington, for example, born in New Jersey in 1820 as a free person, was educated in New England, a graduate of Dartmouth and had a business making portraits. At that time, when photography was cutting-edge technology, Washington had to know the complicated chemistry behind making daguerreotypes and had to have the means to acquire the camera and processing equipment. Washington and other Black photographers represented themselves and their Black subjects with dignity.

Thomas follows in their tradition, incorporating photographs from archives as well as making his own to tell the history of Black people in contemporary culture. In his work, however, that history is a complex one, filled with brutality, exploitation, complicity, resistance, and hope. All of these facets can be found in this exhibition, introduced with directness of presentation interwoven with a sophisticated technical and conceptual approach.

In his series’ “Branded” and “Unbranded”, Thomas uses the language of advertising to reveal to viewers how representation itself works. These pieces reflect upon and call into question the relationship between participants and domineering forces in the culture, such as corporate brands and the sports world.

Hank Willis Thomas (American, born 1976), “Absolut Power”, 2003. Inkjet print on canvas, 53 × 34 inches. Collection of Williams College Museum of Art. Image courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. © Hank Willis Thomas

In the label for the work “Absolut Power”, in which the Absolut Vodka bottle silhouette is refashioned as the British slave-bearing ship Brookes, Thomas is quoted as saying “Racism is the most successful advertising campaign of all time. Africans have…thousands of years of culture. Having all of these people packed into ships and then told they’re all the same, reducing them to a single identity – that’s absolute power.”

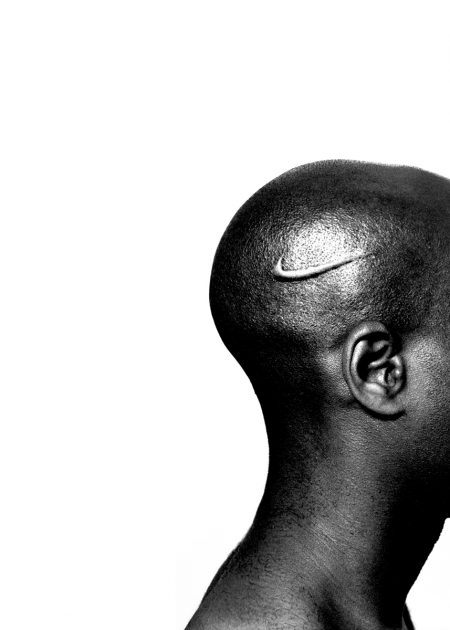

Hank Willis Thomas (American, born 1976), “Branded Head”, from the series B®anded, 2003. Chromogenic print, 99 × 52 × 3 inches. Private Collection. Image courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. © Hank Willis Thomas

In much of the works in “Branded”, signifiers of slavery allude to exploitation in the relationship between Black athletes and the lucrative world of professional sports. Thomas’ photographs use conventions of advertising photography: dramatic lighting, oversized scale, and highly intentional compositions to focus viewers on an inherent message. The Nike swoosh logo is a scar embedded in the shaved head of one subject, in “Branded Head”, and in the chest of another in “Branded Chest”, calling to mind the practice of branding property and whipping disobedient slaves, but also the African custom of scarification as a means of beautification, similar to tattooing. In “The Cotton Bowl”, a reference to the collegiate football game, Thomas makes a cotton field of the gridiron and pits a Black cotton farmer, perhaps a slave or sharecropper, facing off against a college football player. The comparison of the two is clear, both of these people have been exploited, paid practically nothing, for the great financial benefit of others. Add to that the recent reinstatement of much of college football during the time of COVID, in spite of potential health threats to student players.

Hank Willis Thomas (American, born 1976), “The Cotton Bowl”, from the series “Strange Fruit”, 2011. Chromogenic print, 50 15/16 × 74 7/16 × 1 1/2 inches. Detroit Institute of Arts, Museum Purchase, W. Hawkins Ferry Fund. Image courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. © Hank Willis Thomas

Also part of this series, three works of thick 24K gold chain jewelry titled “Am I Not a Man and a Brother”, “Lucy is a Slave with Diamonds”, and “Take Off that Chain Boy, Ya Blinding Me” have pendants that reimagine images of enslaved people as “bling”. These are displayed in cases in front of “Futbol and Chain”, a photograph of a soccer player with a ball attached to his ankle with a chain. Chains are especially loaded symbols for Thomas. The 2005 video “Winter In America”, made with Kambui Olujimi, uses toy action figures to depict the 2000 murder of Thomas’ cousin outside a nightclub during a robbery of gold chains worn by his friends. After his cousin’s death, Thomas began to see his art as a means of communicating to a broader public about issues that he saw were root causes of violence and injustice in society. His work took on a more critical exploration of oppressive structures, institutions, and corporate culture.

The series “Unbranded” consists of vintage advertising campaign photography. Thomas has removed all the ad text, leaving the image to speak for itself. One wall of images, “Unbranded: Reflections in Black Corporate America, 1968-2008” features photographs of Black men, women, and children that depict cultural stereotypes and blatantly racist imagery. On the opposite wall is “Unbranded: A Century of White Women, 1915-2015”. These images promote ideas of purity, servitude, and sexual availability.

The “Branded” and “Unbranded” series’ are presented with an ambiguity that leaves open the possibility of questioning and becoming aware of one’s own role in the situation. Do I buy into this brand? Am I perpetuating cultural stereotypes? Am I supporting ideas or things that exploit myself or others? In a virtual talk with Art Academy students, Thomas said “I am not outside of the culture I’m representing, I’m not sure anyone truly can be, if you speak English, which is a colonial language,” further acknowledging that he had probably spent more money on Nikes than he had ever made from selling his artwork that features their logo.

Hank Willis Thomas (American, born 1976), “Strike”, 2018. Stainless steel with mirrored finish, 33 × 33 × 9 inches. Private Collection. Image courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. © Hank Willis Thomas

Photography is also a point of departure for Thomas’ works in other media. One room in the exhibition features a sculpture series titled “Punctum”, where Thomas has isolated a photographic detail from a news or archival image, made it three dimensional, and cast it in steel or bronze, as one would typically use in casting a public statue or monument. The “punctum”, a term originated by philosopher Roland Barthes, refers to that precise detail in a photograph that sticks in your mind. It is this, the most important communicative device in a photograph, that Thomas transforms into realistic, fully dimensional sculpture. In the human-scale work “Looking For America”, a complete figure of a man is being pulled in four directions by disembodied arms of National Guard soldiers and Civil Rights protesters, a composition taken from a photograph by Danny Lyon in 1964. In “Strike”, based on a 1935 lithograph by Louis Lozowick depicting an encounter between a protester and a policeman, a disembodied arm raised up and wielding a nightstick is grasped at the wrist by another hand, the forearms forming a triangular geometry. This piece, made of gleaming stainless steel with a mirrored finish, resembles a trophy. In these works too, the intentional ambiguity, the incompleteness of the disembodied figures, leaves viewers the opportunity to find meaning in their own questions about what it is they are seeing.

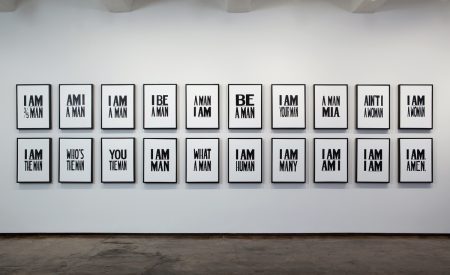

Hank Willis Thomas (American, born 1976), “I Am. Amen.”, 2009. Liquitex on canvas, 25 1/4 × 19 × 1/4 × 2 1/4 inches each. Installation view. Collection of Ulrich Museum of Art, Wichita State University. Image courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. © Hank Willis Thomas

The installation “I Am A Man” features two long rows of white canvases with black lettering. They cover a wall with phrases relating to the text on a sign held up by strikers in the Memphis Sanitation Workers Strike of 1968, where Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr. was when he was assassinated. This strike, and the ubiquitous sign that says “I Am A Man”, was captured in many widely published documentary photographs from that era of the Civil Rights Movement. In Thomas’s installation, the twenty canvases each have a different phrase, among them “I Am A Man” , “Am I A Man”, and “Ain’t I A Woman”. The last phrase in the series is “I Am, Amen”, resolving the piece with words full of gratitude for being alive.

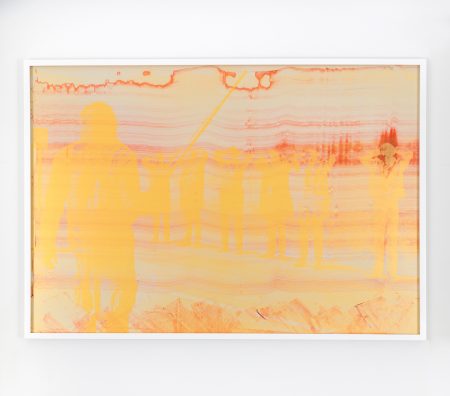

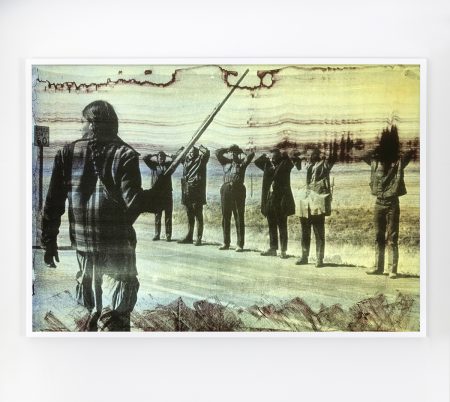

Hank Willis Thomas (American, born 1976), “Wounded Knee (red and gold)”, 2018. Screenprint on retroreflective vinyl, mounted on Dibond, 35 × 49 × 1 3/4 inches. Private Collection. Image courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. © Hank Willis Thomas

Hank Willis Thomas (American, born 1976), “Wounded Knee (red and gold)”, variation with flash, 2018. Screenprint on retroreflective vinyl, mounted on Dibond, 35 × 49 × 1 3/4 inches. Private Collection. Image courtesy of the artist and Jack Shainman Gallery, New York. © Hank Willis Thomas

The final gallery of the show presents highly interactive works, including one series where viewers are encouraged to photograph the pieces with their flash on. At first sight, these pieces look like a salon style hanging of minimalist, Gerhardt Richter style squeegee paintings, sometimes with a single detail of a photograph floating in the middle. When photographed with a flash, the full photograph, in all its detail, becomes visible, surprising viewers with much more visual information. These works are two things at once, with colorful, painterly surfaces of abstract art literally glossing over historical images of protest and violence. If this is not an indictment of the aesthetic distance of the fine art world in the midst of chaos, social unrest, and resistance movements, I don’t know what is.

Don’t miss this one. You can visit the Cincinnati Art Museum by reserving a time online. The show is up until November 8th.

–Susan Byrnes