The Svalbard Global Seed Vault on Spitsbergen Island, Norway opened in 2008 as the world’s largest secure seed storage. Located above the Arctic Circle, it is designed to remain above water in the event of melting ice caps to protect its comprehensive catalogue of the world’s seeds. The opening of this facility fascinated photographer Dornith Doherty, inspiring her to begin a project that has spanned a little over a decade. Doherty’s project, called “Archiving Eden”, explores seed preservation efforts around the world as humanity faces the challenges of climate change and decreased biodiversity in our food sources. A sampling of her photographs from this series is currently on display at the Dayton Art Institute.

Dornith Doherty, Svalbard Global Seed Vault, Spitsbergen Island, Norway, 2010, archival pigment print. Courtesy of the artist, Moody Gallery, Houston; and Holly Johnson Gallery, Dallas, Texas.

The first of two rooms shows documentary-style images from her visits to seed banks and plant conservation facilities around the world. Here, for example, you see the exterior of the Svalbard Vault set into its icy, barren landscape. In “Barley Collection, N.I. Vavilov Research Institute of Plant Industry, St. Petersburg, Russia”, library shelves are densely stocked with sealed glass jars that contain examples of the collection’s over 300,000 varieties of species, with an emphasis on cereal crops such as wheat, rice, barley, oats, and corn. The panoramic photograph “Ancient Citrus Collection, Florence, Italy” shows the grounds of Villa di Castello, former home of Cosimo I de’Medici that houses the largest collection of potted citrus plants in the world. It is thought that this garden was the model for the grove of orange trees in Sandro Botticelli’s painting “Primavera”.

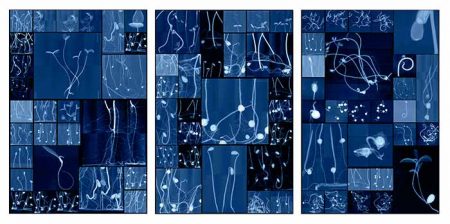

An adjacent room contains photographs of a different nature. These are digital collages consisting of X-rays and lenticular photographs. With this body of work, Doherty adopts a scientific approach to what seeds contain, while also crafting the seed images into forms that recall a variety of cultural and technological histories. Her digital manipulations and compositional choices provide a more expansive context in which to consider a seed’s immediate importance as well as its profound generative implications.

She began depicting seeds as X-ray images because it reflects the process used by scientists to select seeds for saving. Although irradiated seeds are damaged and discarded, seed banks will X-ray a sample of seeds to reveal statistical viability within a larger quantity, ensuring that some of the seeds will germinate when planted. A minimum of five-thousand seeds are required in order to preserve a single plant species. In the dye-coupler lenticular photograph “More Than This”, five thousand small squares, each containing an X-ray of a single seed, are presented in an undulating grid. The grid appears to shift because a lenticular photograph, which combines two images that are visible as one, will have slight variations in each source image and can appear to change as the viewer walks around it. This image wavers between blue and green as the viewer moves, creating a color shift along with an optical wiggle in each seed.

Dornith Doherty, Seedling cabinet I, 2019, digital UV cured ink lenticular. Courtesy of the artist, Moody Gallery, Houston; and Holly Johnson Gallery, Dallas, Texas.

Dornith Doherty, Seedling cabinet I, II, & III, 2019, digital UV cured ink lenticular. Courtesy of the artist, Moody Gallery, Houston; and Holly Johnson Gallery, Dallas, Texas

“Seedling Cabinet I, II, III” also consists of lenticular images derived from X-rays. Here the seeds vary in scale and are organized in irregular rectangular grids reminiscent of the Wunderkammer, or “Cabinet of Curiosity”, a 17th Century European mode of display that contained arrangements of cultural collections and natural artifacts. While the exhibition label explains that the blue and green coloration is meant to signify the cryogenic process of freezing viable seeds and then thawing them to revive them for use, the color also brings to mind the early photographic process of cyanotype (also sometimes called “blueprint”). This process, invented in 1841 by scientist and astronomer Sir John Herschel, was often used to make what are known as “photograms”, where an object is placed on light sensitive paper, exposed to a bright light or sunlight, and then developed to show a silhouette of the object. Doherty’s “Cabinet” images allude to this era of photographic history, especially to the work of 19th Century botanist and photographer Anna Adkins, the first person to publish a book using photographic illustrations. Her 1843 volume was called “Photographs of British Algae: Cyanotype Impressions.” For Adkins, an amateur botanist and close friend of Herschel’s and early photographic inventor William Henry Fox Talbot, amateur pursuits in areas such as botany and photography were permissible for a woman of her upbringing and social class at that time. Doherty’s work, like Adkins’, connects to current science and technology while incorporating aesthetic experimentation simultaneous with species documentation.

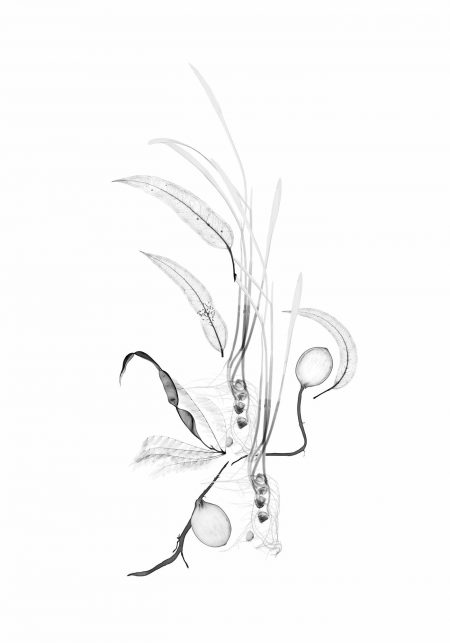

Doherty also connects the relationship of plants to global trade and the resulting adaptation of culture as well as nature. The digitally altered X-ray of a eucalyptus plant is the basis of the images “Eucalyptus I & II,”. Outlines of the stems, buds and leaves of the plants are a deep blue on a white ground. This color palette references Delftware, an iconic blue and white ceramics found in the Netherlands that developed as a result of global silk and spice trade with China that also introduced its blue and white porcelain as a luxury good.

Dornith Doherty, Columbian Exchange III, 2014, archival pigment print. Courtesy of the artist, Moody Gallery, Houston; and Holly Johnson Gallery, Dallas, Texas.

The image “Columbian Exchange III” references the crops exchanged between America and Europe by Christopher Columbus, introducing new species to different continents and forever shifting the ecological landscape as the plants adapted to new environments. Doherty’s image consists of a digital collage of X-rays sourced from her native Texas: teosinte (an ancestor of corn), eucalyptus, mesquite, and pecan plants are combined in a still-life composition. Both the “Eucalyptus” and “Columbian Exchange” images, interestingly, are visually linked to another body of work in the Dayton Art Institute’s collection. Sister Mary Alice McFarland, a nun and X-ray technologist at Good Samaritan hospital in Cincinnati, applied for and received a patent for a process she called “Flor de Rey”, a process of X-raying flowers for the purpose of ”producing an artistic picture”. The DAI holds twenty of these works depicting flowers such as the Bird of Paradise, Jack-in-the-Pulpit, Fuchsia, in black and white, and a few with hand coloring. While Sister Mary Alice’s work was not known to Doherty, exhibition curator Kathryn Ryckman Siegwarth has highlighted these works in the exhibition label.

My favorite work in the show is called “Finite”. This simple image brings the concept of the critical importance of seeds into high relief. In a nearly four foot diameter circle, Doherty has digitally placed hundreds of ptilotus spathulatus seeds against a deep black ground. They circumnavigate five dense white eucalyptus seed pods placed near the circle’s center. At a distance, the white X-ray seeds and pods look like five suns surrounded by comets or shooting stars. Upon closer inspection, the viewer is absorbed into a cosmos that is at once microscopic and galactic in scale and metaphorical inference. The mesmerizing visual space is both a Petrie dish and a porthole view into the universe. What we are seeing is the genetic material that holds past and future at once, as well as the speck of difference between life and death on this planet, which is up to us to safeguard.

–Susan Byrnes