Tucked within a plaza of galleries you’ll find the William Turner Gallery in Santa Monica. On view until November 28th is the Black Madonna exhibition by Mark Steven Greenfield, a native Angelino (the exhibition is also available to view online, though you’ll miss much of the size and scope). I’d glossed a couple of the Black Madonna images online but hadn’t quite identified the details, so I was pleasantly surprised to find a number of layers in these subversions of Renaissance paintings. Among the threads being weaved here are afro-futurism, history, celebration, mourning and revenge. Before I peel away these layers, though, I want to start with the largest piece in the exhibition – which also happens to be the outlier. As you walk into the large, open gallery space, the room is lined with the 17 Black Madonna’s that make up the heart of Mark Steven Greenfield’s exhibition. However, in the back left corner, a small pocket holds 4 large ink and acrylic drawings, which reminded me a bit of Keith Haring. One of them is Greenfield’s entry into the world of Zong art, which catalyzes the work performed by the exhibition.

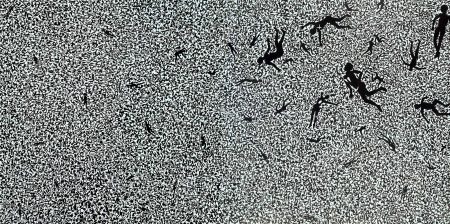

“ZONG”, 2019

Ink and Acrylic on Duralar

36” X 70”

In her beautifully devastating book In the Wake, Christina Sharpe theorizes the wake – the ripples in the water behind a ship – as the hauntological afterlife of slavery. She writes, “I use the wake in all of its meanings as a means of understanding how slavery’s violence emerge within the contemporary conditions of spatial, legal, psychic, material, and other dimensions of Black non/being as well as in Black modes of resistance” (14). Slavery’s ripples enduringly remain a haunting presence on blackness and western civilization. She reads a poem by NourbeSe Philip’s called Zong!, which unsurprisingly shares its origin with Greenfield’s piece. They reflect on the horrible slave ship, the Zong, from which slaves were thrown overboard for insurance purposes. People, in that case, were property that was going to spoil because food and water were too scarce to nurture them. She cites Philips calling her poem “hauntological,” because it, like Greenfield’s piece, wrestles with the effects of the specter of slavery over the generation of blackness. These Zong pieces are what Sharpe calls “wake work,” which works to apprehend modes of existing and generating realities of blackness. Visually, Greenfield’s piece is a sprawling well of fractured lines which all weave together without specified shapes. A few different junctures take the shapes of black bodies, falling into the abyss of the ocean to which they were cast, and – if we look closely – connect with the lines throughout the piece. To me, these lines abstractly resemble the conglomerations of people all trying to formulate modes of existence in the wake. I read these shapes as the haunting energies that permeate through Greenfield’s exhibition.

In each and every Black Madonna painting, we can see discs with these ridged black lines filling them. Greenfield has said that they emulate mantras of transcendental mediation, giving the paintings a meditative property. They resemble the same lines that make up the bulk of the Zong piece, connecting them to that piece and situating them within the wake. I see the presence of the discs – stemming from Zong – as beginning the work of resistance that each painting builds upon. The premise of Greenfield’s project comes from the mysterious existences of Black Madonnas found in various countries. They aren’t granted officiality by the church, but their mysterious origins bring a unique mix of pagan symbolism into the Christian fold – or perhaps, the Christian wake, which obviously had its own role in oppression of blackness.

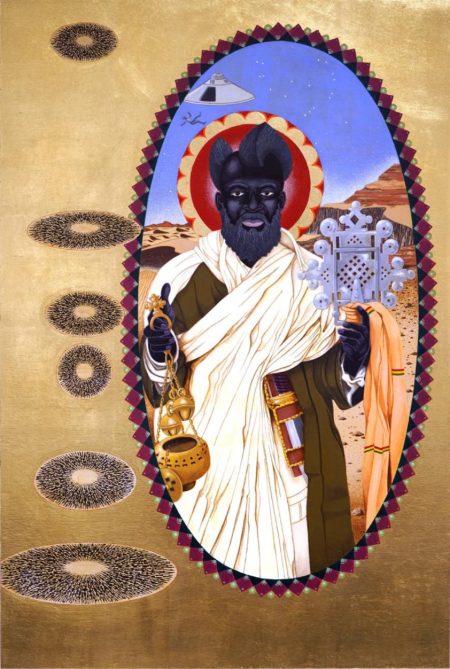

“St. Moses the Black, aka Abba Moses the Robber”, 2020

Gold Leaf and Acrylic on Wood Panel

35” X 24”

The meditative discs of the wake also grant the paintings an afro-futurist tone. Many of the paintings contain these futuristic tones as Greenfield uses vivid color palettes, baroque imagery and in some cases explicit sci-fi imagery. One of my favorite pieces depicts Saint Moses the Black – one of a handful of paintings devoted to real historical figures. His hair is strikingly shaped and an ethereal, planetary-looking circle floats behind his head. In the background we see a flying saucer abducting a mysterious figure. This handful of paintings seeks to reclaim figures that have been suppressed by western historicization, recognizing them as saints in their own right. They’re beautifully otherworldly depiction of figures that seem imbued with power that transcends the familiar, bridging the heterogeneous cultures and beliefs that might have guided people who had had Christianity imposed upon them. The wake work of these pieces, which remains consistent across the board, is to reclaim and reframe the figures by way of reimagining and taking over the dominant cultures that had oppressed them.

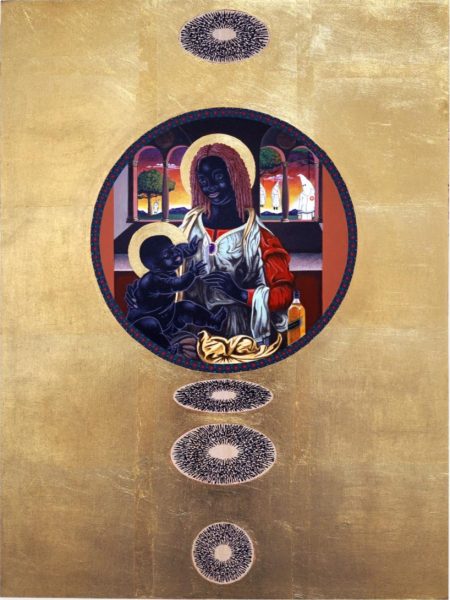

“Bad Apples”, 2019

Gold Leaf and Acrylic on Wood Panel

24” X 18”

Greenfield shows a fondness for irony in some of the Black Madonna images that generate revenge fantasies. A significant portion of the collection depicts the Black Madonna holding baby Jesus, while the background contains a version of white supremacists suffering. A few of them recall the afro-futurism that I alluded to before, bringing in more flying saucers to abduct Nazis. The revenge fantasies might prove to be heavy handed for some, though I appreciate the subversion taking place. One image shows a background of KKK members hanging from trees. In this image, like the others, the Madonna and baby Jesus appear tranquil and safe. The revenge fantasy imagines the oppressed experiencing the satisfaction of vanquishing the oppressor and finding meditative peace through that subversion. To the right of the Madonna sits a bottle of Hennessey, perhaps a part of the celebration within the image, and undoubtedly a celebration of a drink that’s become a consistent presence in hip hop and black popular culture. The fantasy is interesting, but these cultural allusions really deepen the nuance of the paintings.

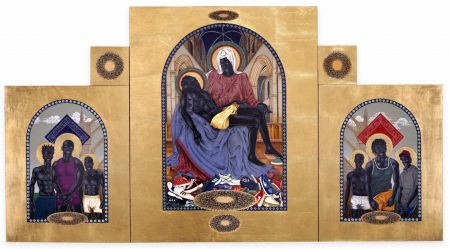

“Collateral”, 2020

Gold Leaf and Acrylic on Wood Panel

30” X 56”

These allusions show up strongly in my personal favorite from the exhibition. One of two trifold paintings, Collateral brings us right into the fold of contemporary Los Angeles. The left and right sides depict three young men backgrounded by a red and blue bandana respectively, alluding toward LA gang culture. In the middle, the Madonna holds the body of a young man who was a collateral victim of the wake, which here takes the guise of gang violence. It’s a poignant piece of mourning that calls to mind John Singleton’s Boyz in the Hood or Spike Lee’s Chiraq. The value of the renaissance frame, however, gives it a religious quality of memorialization. Though many of the paintings generate memorialization, this one does it in a particularly emotionally pointed way, bestowing honor on forgotten victims. At the feet of the Madonna lies a large pile of sneakers, broadening the spectrum of victims being honored, as well as celebrating sneaker culture and those who find community in the pockets of black culture that a few of these images allude to. Collateral finds a way to perform memorialization, mourning and celebration simultaneously without rendering the gang participants as villains, an important contextualization with the paintings that depict the real, white supremacist villains. It acknowledges gang life as one of the complex cultural pockets within the struggles of black life within the wake of history.

The biggest strength of the exhibition is it’s multidimensional quality. The pieces, on their own, are interesting. When we take them together, however, they really collaborate in turning the gallery into the sacred setting that Greenfield might envision. You’ve got saints, martyrs and vanquished villains. The Madonna and the baby Jesus exist differently in these ornate, renaissance settings, which meld fantasy and religion with radical black politics and ordinary, black popular culture. They strike toward sacred institutions in order to subvert, and at times recast them with striking irony. Haunted by the wake generated by the Zong, the exhibition performs a worthwhile collection of artistic resistance.

–Josh Beckelhimer