View of exhibit

The backstory is important here. The movie The Monuments Men brought to light the very intriguing and powerful story of mostly middle-aged men and women – primarily art experts – who volunteered for the Army to rescue and hide art masterpieces, books and rare documents from the Nazis during WWII. These efforts were led by the “Monuments Men,” members of the Monuments, Fine Art, and Archives program, established in 1943 under the Civil Affairs and Military Government Sections of the Allied armies. This group of three-hundred forty-five mostly American men and women including one Cincinnatian, the late Walter Farmer, a well-respected interior designer and art collector, applied their civilian talents as museum directors, curators, art historians, archaeologists, architects and educators to save, quite literally, Western civilization’s treasures.

These special military volunteers even risked their lives in some cases to see that priceless cultural artifacts were not destroyed. Many of us did not know about this unique set of circumstances of the war until The Monuments Men movie came out in 2014. In total it is estimated there were over five million objects, manuscripts and masterpieces of art from throughout Europe, from Germany’s museums and tragically from private, primarily Jewish collections that had been or would have been confiscated or destroyed. It is not possible to do this exhibition and topic justice without giving equal time to the facts and history of this endeavor, as it is to discuss the paintings and documents that are in this exhibition.

If you had visited Europe any time after World War II, you would have witnessed the destruction as Europe struggled to rebuild after the extensive bombing that took place from 1939 through 1945. Even if you did not personally witness any of this, books, reports on TV and countless photographs documented the destruction caused by WWII. But we don’t think about how monuments, art works, and treasured architecture were not all destroyed. Here are some examples: in advance of the Nazis, the Monuments Men evacuated 400,000 works from the Louvre, including the Mona Lisa, which they shuttled to safety six times. Just ahead of the German invasion of the Soviet Union, they emptied and stashed more than two million works from the Hermitage. Two million. If you have taken an art history class, picture your professor in military uniform packing, dragging and hiding Rembrandt and Vermeer paintings in underground salt mines or underground church vaults while Hitler’s troops were nearing. It is mind-blowing.

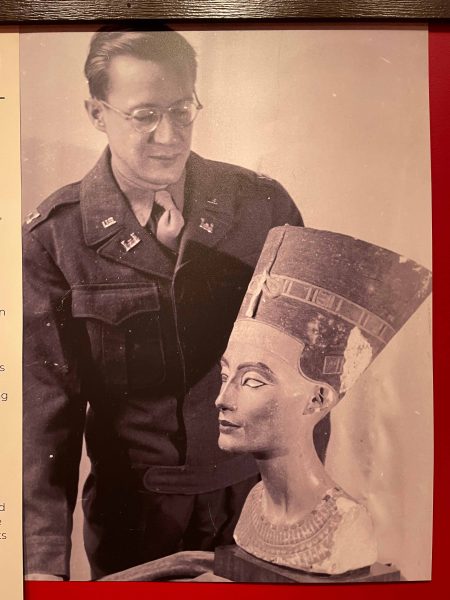

Photo of Monument Men with the Berlin Nefertiti.

But it wasn’t only Nazi plunder they had to guard against. It was left to the Monuments Men to figure a way to save da Vinci’s Last Supper, painted on the refectory wall of the convent at Santa Maria delle Grazie, before the Allies bombed Milan. By jury-rigging a scaffold of steel bars and sandbags around the wall, they saved the masterpiece. After the raid, it was the only wall in the refectory still standing. By using aerial photos, Monuments Men diverted Allied airmen away from many important sites, including the Chartres Cathedral. When a cultural site ended up an unintended target, Monuments Men rushed in to make repairs before more damage or loss occurred.

So why is this special exhibit taking place here? Several members of the board at the Cincinnati Art Museum personally knew and remembered Cincinnatian Walter Farmer who was among the prominent Monuments Men volunteers. When the new Director Cameron Kitchen came on board, they rolled out the idea of having an exhibit spotlighting the rescued art, the story and the Cincinnati man who was a large part of this significant art rescue mission. The museum could not turn away from such an amazing story with a strong local connection.

This exhibition “tells the story of how and why some of the world’s most iconic European paintings left Germany immediately after World War II and toured the United States in what became the first blockbuster art exhibition of our time,” says the museum press.

People familiar with 20th century art generally know that from the rise to power of the National Socialists in 1933 through the end of the war in 1945, Nazi policies and practices resulted in systemic repression of modern artists in Germany, the looting and forced sales of artworks – especially from Jewish collectors – across Europe, and artworks changing hands through other unethical or questionable transactions. It would be in another article that I could write about this repression of contemporary European artists many of whom were fortunate enough to emigrate to the United States; most settled in New York city and heavily impacted young American artist like Jackson Pollock. Early Pollock and other Abstract Expressionisits was heavily influenced by these European Surrealist artists.

We are so fortunate that the board members who knew Walter Farmer envisioned this exhibition at the museum and we are further fortunate because this is the only venue for this important historical exhibition. Peter Bell, the museum’s Curator of European Painting, Sculpture and Drawing explained that he and co-curator Dr. Kristie Nelson of the University of Cincinnati requested four paintings from the State Museum of Berlin as centerpieces of this exhibition.

Sandro Botticelli’s Ideal Portrait of a Lady, 1475–1480

tempera on poplar panel, 21 13/16 x 16 15/16 in., State Museum of Berlin

So lets look at the stars of this exhibition, starting with the stunning Sandro Botticelli’s tempera Ideal Portrait of a Lady. Owing to it being painted in tempera paint that requires continuous minute brushstrokes to create the illusion of blending since tempera dries almost immediately upon contact with the panel upon which it is painted, this painting shimmers before us as a mirage of female beauty. Thousands of carefully choreographed brush strokes automatically create a reverential and otherworldly impression to my mind. Up close each delicate and painstakingly applied brushstroke is evident. This is in contrast to oil paint which is soft and which can be swooshed about on the canvas creating whole areas of the same color with all the brushstrokes melting one into the other. It is not until Impressionism that we have a real break with the dominant Renaissance and post-Renaissance painting styles and oil paint is deployed to create staccato brush strokes that mimic the staccato rhythm of life of the Industrial Revolution. But Botticelli’s painstaking tempera portrait of Simonetta Vespucci shows a young woman whose each eyelash is a beautifully curved brushstroke. You are looking at this painting as if you are seeing it between breaths. The exhibition is worth it for this painting alone.

The museum has paired this painting with works from the museum’s permanent collection by artists of Botticelli’s time that were represented in the “202 Exhibition,” such as Andrea Mantegna and Peter Paul Rubens. In this manner we have a feel for how the original Monuments men’s “202 Exhibition” would have looked. Two-hundred two paintings from the sixteenth- to eighteenth-century that were from the State Museums in Berlin were recovered by the US Army in a salt mine at the end of the war. Their long and controversial journey followed; they traveled to the US in 1945 and were exhibited in fourteen cities across the country, before returning to occupied Germany and, decades later, back to the rightful possession of the State and the German people. So the exhibition was called the “202 Exhibition.” The paintings’ temporary transfer out of Germany was met with outcry on both sides of the Atlantic, but their exhibition in America was greeted with huge enthusiasm, drawing almost 2.5 million visitors.

Another painting in this exhibition that was from the original “202 Exhibition” is also from the approximate time-period as the stunning Botticelli. This one is an early example of oil painting that was coming into use in the fifteenth century. It is attributed to Konrad Witz. The Crucifixion, circa 1440–50 is small and typically reverential with the cross seen frontally and centered in the composition. Interestingly, it is painted in a manner similar to the way tempera is handled. Since oil paints were just being developed it is natural to have artists use this new kind of paint in the manner that they had used tempera. It makes for a simple and slightly stiff rendition of the religious theme. Later, artists like Rembrandt would push oil paints to it limits, creating lush and smoldering darks and sparkling lights with bravura brushwork and blending that only oil paint can achieve.

There are two more wonderful paintings in the exhibition beside the Botticelli. They are Philips Koninck’s commanding Panorama of Holland circa 1655–60, an oil on canvas that is an authoritative landscape in the manner for which Dutch artists came to be known. It is worth noting that the Dutch artists (think Rembrandt and his Guild) really put Western painting of all genres on the map: mythical and biblical paintings and luminous and arrestingly life-like still life paintings. Most importantly the Dutch created the domestic genre paintings where we think of paintings like The Jolly Companions originally attributed to Frans Hals and in the 19th century revealed to be the work of one of the few women in the Guild with Rembrandt – the great Judith Leyster. Oil paint in Dutch artists’ hands were miracles on canvas or panel. I point this out because so often we think of the great Italian masters of the Renaissance and Baroque eras, Michelangelo, Veronese, Titian, Rubens and so on when we think of Old Master oil paintings. We overlook the Dutch old masters so The Panorama of Holland reminds us that the Dutch artists were heavy lifters in the Renaissance just as the Italians were.

Antoine Watteau, The French Comedians, 1714, oil on canvas, 15 1/4 x 19 1/16 in. State Museum of Berlin

Let’s not leave out the French! The fourth painting in this exhibition from the original “202” is Antoine Watteau’s The French Comedians of 1714. It is a cabinet-sized oil painting, smallish at 15 1/4 x 19 1/16 inches but dreamy and inviting. The troupe of comedians at the center are painted in brighter colors and the light immediately drops away in the imaginary garden, much as the light fades behind the actors on the stage. The French Comedians is considered one of Watteau’s most important paintings and he painted a companion piece, The Italian Comedians. I am not sure why this duo of works is among Watteau’s most significant, a point made in the wall text. I saw a large compliment of Watteau’s work in the Louvre and they are all delightful, smallish and stylish, poetic in the same way Pierre Bonnard’s paintings can be said to be poetic at the end of the 19th century. Maybe the painting is a bit larger for Watteau so it is considered more significant?

Besides highlighting the four paintings on loan from the State Museum of Germany, the exhibition includes art work from the museum’s own collection that are very similar to paintings in the original touring “202” exhibition. This gives the viewer a feel for what the original exhibit would have been like. The exhibit also addresses Monuments Man Walter I. Farmer. He “served as the first Director of the Wiesbaden Central Collecting Point in Germany, where after the war artworks were gathered, documented and prepared for return to their rightful owners. Farmer was responsible for assembling the Monuments Men from across Europe to draft the Wiesbaden Manifesto, a document protesting the shipment of paintings to the US. It may have been the only collective act of protest by US officers in World War II. Following the war, Farmer was a resident of Cincinnati and supporter of the arts in the region for almost 50 years.”

Various documents related to Walter Farmer and of special note are the actual Commander’s Cross of the Order of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany on loan from family, are on display here. That a Cincinnati native received this honor that required the nomination by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs is to be celebrated. Walter Farmer flew to Bonn Germany in 1996 to receive this medal. Viewers may also be interested in the accompanying catalog written by the exhibition co-curators.

I feel obliged to add this footnote from the NEH website from 2007: https://www.neh.gov/about/awards/national-humanities-medals/monuments-men-foundation-the-preservation-art Inspiration came to Edsel quite accidently. Barely forty at the time, he was in Europe, after selling his lucrative oil exploration business, to ponder his life’s next big adventure. He was standing on the Ponte Vecchio, the only one of Florence’s fabled bridges the Nazis hadn’t blown up during their 1944 retreat, when he began to wonder how, despite the war’s widespread destruction, so many paintings, sculptures, monuments, cathedrals, and museums had survived. Who, he asked himself, had saved it all?

Robert Edsel has detailed the Monuments Men bravery and resourcefulness in an abundantly illustrated book, Rescuing Da Vinci: Hitler and the Nazis Stole Europe’s Great Art—America and Her Allies Recovered It, 2006. He also coproduced The Rape of Europa, an NEH-supported documentary focusing on the Monuments Men, and late last year he convinced Congress to pass a resolution honoring them. Recently he established the Monuments Men Foundation for the Preservation of Art, whose mission is “to preserve the legacy of the unprecedented and heroic work of the Monuments Men by raising public awareness of the importance of protecting and safeguarding civilization’s most important artistic and cultural treasures from armed conflict.”

Sixty-two years after the end of the war, only a dozen of the Monuments Men are known to be alive, the youngest, former sergeant Harry Ettlinger, now in his eighties. This puts Edsel, who believes there may be more still living, in a race against time. He has been ferreting out their details for the biographies posted on his Web site (www.monumentsmenfoundation.org)—so far he has collected 103—and personally meeting with the survivors.

Once their wartime duties were behind them, many of the Monuments Men went on to distinguish themselves in the arts, including Lincoln Kirstein, who founded the New York City Ballet; James Rorimer, who served as director of the Metropolitan Museum of Art; and Charles Parkhurst, chief curator of the National Gallery of Art. But, as the years passed, their wartime contributions sadly slipped from notice. As Edsel himself discovered, there was hardly a mention of the Monuments Men in all the vast literature of World War II. His unrelenting curiosity, energy, and deep admiration have brought honor to those heroes who saved Europe’s treasures. “Their search,” says Edsel, “was the greatest treasure hunt in history.”

–Cynthia M. Kukla