Before heading to the LA Arts District for Hauser & Wirth’s presentation of Everrrything by Lorna Simpson, one would benefit from a brief reflection on the history of the artist. While working on her MFA in Visual Arts at the University of California at San Diego in the 80s, one of her teachers was the French filmmaker, Babette Mangolte. Mangolte most notably worked as the cinematographer for many of Chantal Akerman’s films, the most famous of which is Jeanne Dielman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles. Jeanne Dielman is famous for stretching a three-day narrative across a 201-minute film. Those filmmakers were interested in exploring time as a mechanism for engrossing audiences into the ordinary, depicting mostly a single mother completing everyday tasks. The film slowly details the breakdown of the fractured identity of a woman working to fit into a flawed societal mold. It should come as no surprise that Simpson’s own interests in time which began developing in that early period continue to pervade her newest exhibition. By way of cut up collages, majestic paintings and sculptures, Simpson interrogates effects of time on identity, race, gender, and the environment. The exhibition only includes one video piece, but the collection is clearly inflected by the skill of a visual artist versed in structural filmmaking.

Before entering the gallery rooms visitors will first encounter a series of outdoor sculptures. The sculptures are made up of flat rocks stacked upon each other, the uppermost surfaces functioning as tables. Smooth round bowls sit atop the stacks seemingly hinting at old forms of utility. The sculptures themselves are surprisingly simple. Though rough around the edges, they’re completed by the elegant bowls. They act as a useful introduction to the exhibition by inflecting the space with three dimensions. The sculptures serve to supplement the paintings that follow by loosely functioning as models of some of the icy landscapes depicted in the paintings. The final piece of the sculpture collection, which can be found inside among the paintings, is also the culminating piece. Rather than a bowl, the stack holds a large, ice cube. The cube (which is made of glass) does not melt, demonstrating Simpson’s use of slow time to reflect on human relations with the environment.

Lorna Simpson

Hypothetical Physical States

2021

Glass cloche, glass block, bluestone, wood, paint

Unique

The paintings follow by drawing up the environmental vision of the exhibition. The first and second room contain broad views of natural landscapes painted and screen-printed onto fiberglass. They appear to be arctic landscapes – we might conceive them as landscapes that have existed since long before humans began spreading across the planet. The deep hues of blues (which can appear red if the light refracts at the correct angle) and greys generate images that seem almost beyond human imagination. They take on a grand, mystical quality as they not only stretch time but attempt to stretch landscape across the fiberglass. They should activate an appreciation for what could be framed as alien worlds yet remain very much of our world. The grand distance of the works recalls the ice caps as emblems of environmental degradation, reminding us of the often out of sight landscapes that suffer at human expense. These are landscapes that have been gradually chipping and melting away.

Lorna Simpson

Storm

2021

Ink and screenprint on gessoed fiberglass

191.8 x 149.9 x 3.5 cm / 75 ½ x 59 x 1 3/8 in

Beneath the surface layer of some of the works lie clippings and images. Some of the images are of faces while the clippings appear to be from newspapers and magazines. The inclusions of these fragments haunt the paintings and should haunt visitors. The paintings, which already expand our visions of environmental time, encourage an expansive view of history. They recall histories of slavery and colonialism. The paintings recall these important ghosts haunting our current cultural landscape, which we may never fully come to terms with. They also recall how climate change and its degrading effects on icy landscapes are indelibly intertwined with these haunting histories. The pieces argue that the systems that have driven each of these ghosts all stem from the same roots. The collection complicates nodes of time that cannot be neatly established, hinting that there aren’t neat beginnings and endings to the cultural forces and ghosts that inflect today’s culture.

Lorna Simpson

Reoccuring

2021

Ink and screenprint on gessoed fiberglass

259.1 x 365.8 x 3.5 cm / 102 x 144 x 1 3/8 in

In the next room viewers will encounter a different set of paintings. These four take on darker hues. They seem to carry the ghostly, haunting qualities present in the previous set of paintings. Each of them centers a black woman. Simpson’s grand portraits here imagine these subjectivities as ones that struggle to make themselves visible and heard. But of course, they haunt. They refuse to be brushed away, rather looming across the largest fiberglass sheets in the entire gallery space. They also, however, hint at the expansion practiced by the next set of pieces in the following room. A couple of them are peppered with constellations and imagery of space, taking them into a galactic, transcendent realm. Here the exhibition expands time and space beyond the Earthly landscapes, posing questions about how identity can be expressed and how humans and blackness can transcend ghostliness.

Lorna Simpson

Observer

2021

Ink and screenprint on gessoed fiberglass, bluestone, wood, paint

Panel: 365.8 x 259.1 x 3.5 cm / 144 x 102 x 1 3/8 in

Overall: 391.2 x 259.1 x 86.4 cm / 154 x 102 x 34 in

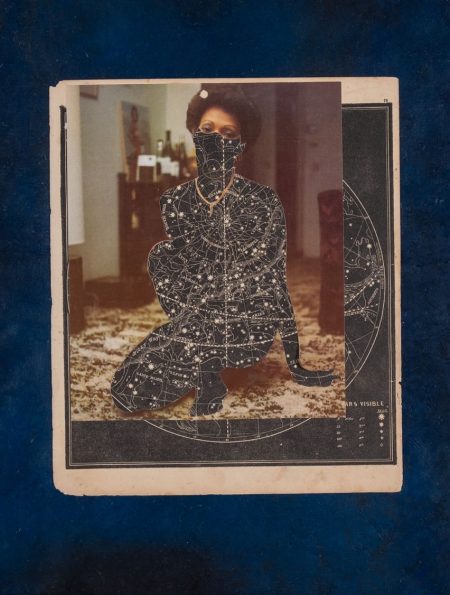

In the following room, the exhibition transitions to collages that will be familiar to followers of Simpson’s work. This wide collection of collage work utilizes pages of Ebony and Jet Magazines. Each page presents an image of a black woman with sections of the body cut out. These pages are overlaid atop what might be pages from an astronomy book. The pages sketch constellations and galaxies, which poke through the silhouettes of the woman that they’re combined with. The collages are mystifying, especially with the support of their dark blue backgrounds. The backgrounds support the collages in generating a feeling of looking up at a night sky. There is tension here, just as there was in the previous room. Multiple readings could be extracted from these collages. On one hand, they could be read as responses to cultural erasure. Each figure only includes fragments of the faces and bodies of the women. They are generally swallowed by the galactic base layers. Their bodies here have literally been erased. Viewers might notice that all the mouths are cut out, as if these women have been silenced by way of the magazine’s visual harnessing of their images.

Lorna Simpson

Everrrything (Detail)

2021

Collage and pastel on handmade paper, 10 parts

Each: 61 x 43.2 cm / 24 x 17 in

Each framed: 65.7 x 48.3 x 4.1 cm / 25 7/8 x 19 x 1 5/8 in

These images might also be read as nostalgic celebrations of the women from the cutouts. The collages, as wholes, are certainly visually striking. They might suggest that there are galaxies inside the minds and bodies of these women. If we’re to read them as culturally silenced, there is a greater future for them. The work of expression will lead them past the cultural bindings of the era that these magazines come from. That era, of course, was not so kind to women, particularly women of color. They depict, quite literally, fragmented identities. Their identities are both somewhere in a 50s magazine and somewhere off in space. They, like the rest of the exhibition, certainly continue the project of expanding and complicating time. They recall how time’s movement consistently impacts the evolution and relations between the environment, identity within our culture. The complicated explorations of identity blend histories by calling on ghostly pasts and pointing toward cosmic futures.

Lorna Simpson

Stars from Dusk to Dawn

2021

Collage and pastel on handmade paper, 3 parts

Each: 61 x 43.2 cm / 24 x 17 in

Each framed: 65.7 x 48.3 x 4.1 cm / 25 7/8 x 19 x 1 5/8 in

–Josh Beckelhimer

Everrrything is on view at Hauser & Wirth through January 9th, 2022