It is a genuine tragedy that the art of Antonio Pietro Narducci (1915-1999) is not a staple within Abstract Expressionism but, luckily, curator Inhee Iris Moon has prompted what is hopefully the first step in changing this unfortunate art historical shortcoming. One reason why Narducci’s work and name is perhaps not as well-known as it should be is that the artist was reclusive and his life was ridden with drawbacks that stilted him from achieving the fame of a Pollock, de Kooning, or Rothko—indeed, Narducci was never interested in such fame. As a young artist, Narducci exhibited at a New York gallery where, after the show’s closing, the gallery took a sledgehammer to his canvases, complaining that they were gargantuan in size and thus immovable. Most understandingly, Narducci was beyond frustrated that his works were tarnished. Later on, in the mid-1950s, Narducci’s private art dealer disappeared with almost two hundred paintings which, to this day, have yet to resurface. Narducci was utterly uninterested in the superficial vagaries of the art world and its coeval market, being committed to pursuing a genuine practice, both structurally and theoretically. Nowhere is this clearer than in the 24 paintings and works on paper that comprise Kate Oh Gallery’s magnificent exhibition “Narducci.” Here one is allotted an impressive, variegated, and stylistically diverse array of Narducci’s work in the 1950s, 60s, and 80s.

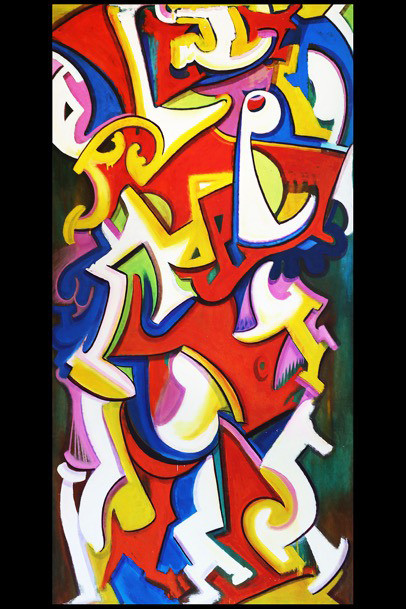

One could easily write an entire book about this show, and Narducci’s works most certainly merit such an endeavor. The works are each numbered but “Untitled”, yet they are thematically rich enough that a title would be superfluous. Contra the field paintings of Mark Rothko, Barnett Newman, and Clifford Still, Narducci readily engages in the figurative. In many of Narducci’s works, we can make out familiar images and figures, such as men suited in bleached white playing guitar and drums, their bodies bouncing and gyrating between slivers of sun. Given Narducci’s lifelong interest in musicality—notably, Narducci was enchanted with, and would often paint to, Igor Stravinsky’s “Rite of Spring”—such motifs heavily figure in many of Narducci’s works. However, it is not a commitment to the icons of musicality that springs to the fore—rather, Narducci’s paintings are committed to the mode of musicality, and the concept of movement inherent to it. Thus, even in his more abstract works, we can make out the figures of men or women collapsing into one other, with such characters bleeding through Rorschach-blotches of stygian black and mossy green. Movement is thus prioritized above and beyond the bodies that move.

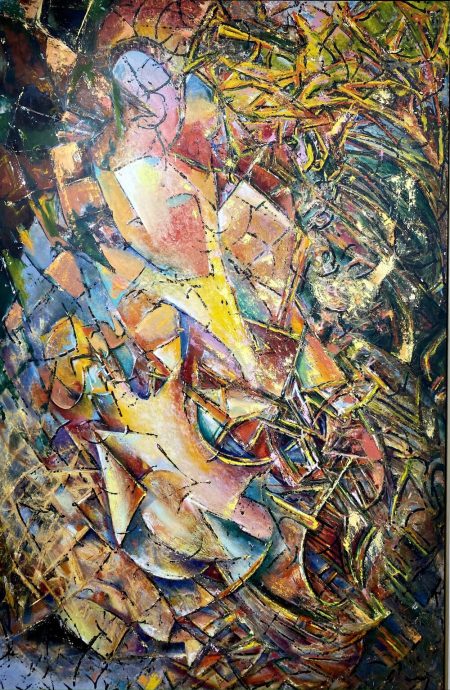

Thus, both Narducci’s paintings and drawings alike eschew the iconic as such, instead proffering the mode of perceiving as key—there is a vapor that thematically sets these works together, one that culls intuition. It is thus fitting that this theme of pursuing the intuitive comprises Narducci’s lifelong pursuit such that, in 1985, when Narducci was seventy years old, he found himself at his artistic apotheosis. This point was one of contact with the “transcendental”, albeit it simultaneously involved a medium-based, empirical discovery. Narducci, an early adopter of acrylic pigments, mixed his paint with India ink, ammonia, and rainwater, so as to muster an amalgam that imitated earthly tones. This discovery was accompanied by a shift in Narducci’s style, as his later works demonstrate an interest in imitating the tones and colors of bark, moss, the sun-bleached sky, and crag-ridden rivers, while divorcing these from any icons—there are no trees, plains, or riverbeds to accompany these raw slivers of sense-data. That is, the phenomenal “intuition” of nature is preserved without its figure. Narducci considered this a genuine movement beyond American Expressionism, and he termed it “Transcendental Aesthetics.”

One here might recall Kant’s “transcendental.” According to Kant’s Critique of Pure Reason (1781/1787), that things in themselves are transcendentally real means they are real with respect to the transcendental level of reality, i.e., that they exist at the point of view of fundamental ontology and are mind-independent. This is distinct from empirically real things, which are located at the empirical level of reality and exist mind-dependently from the point of view of fundamental ontology; transcendental reality is also distinct from empirically ideal things, which are mind-dependent but do not exist from the view of fundamental ontology—things like hallucinations, fictional objects, and illusions. For Kant, (transcendental) things in themselves are, famously, not representable. Narducci’s practice is not one of attempting to represent what is not representable—this is not the “transcendental” that Narducci is concerned with. Indeed, for Kant, there is, at once, the aforementioned transcendental register of (mind-independent) things in themselves, and the transcendental faculty, wherein the characteristic forms of our cognitive faculties determine the conditions of experience. Such transcendental conditions of experience need to be taken up/fulfilled for a resulting cognition to be able to truthfully represent an object of experience. Narducci’s interest in the transcendental seems not to be representing that which is celestial and beyond the world of empirical appearances. Despite an otherworldly, celestial motif of many of Narducci’s late works, there is always an intuitive sense of the earthly that tethers these paintings to our world of experience. Rather, Narducci’s works examine the conditions of perceiving, and what a field of representations, not yet “taken up” and organized into a series of empirical representations in space and time, would look like—an “as if” that gives an image to the representing work accomplished by our transcendental cognitive faculties.

Thus, on the one hand, Narducci’s works are simply beautiful and visually engaging, utterly unique from his contemporaries. One ought to appreciate the canvases that adorn Kate Oh Gallery’s walls for this reason alone. But, simultaneously, they are theoretically profound and philosophically rich. This is what makes Narducci inimitable and deserving of the highest of praise, even if this praise comes too late. I must underscore that it is a genuine tragedy that many of us are not familiar with Narducci’s name or his body of work. Luckily, Kate Oh Gallery has taken us one step forward in changing this.

–Ekin Erkan