In Alexander Brest Gallery’s first exhibition of the 2021-2022 academic year, Bill Davis, photographer and Associate Professor of Art at Western Michigan University, asks his viewers to reevaluate their relationship with darkness and become more cognizant in how the presence of synthetic light in the nocturnal landscape creates an unhealthy imbalance in ourselves and the environment. The 19 dye-sublimation photographic prints on aluminum included in the exhibition, were captured during Davis’s grant funded exploration of artificial light in the United States, Spain, and Peru, between 2016 and 2020.

Installation view of Bill Davis’s “No Dark in Sight,” in the Alexander Brest Gallery on Jacksonville University’s campus. Photograph taken by the author.

At the joint exhibition opening for “No Dark in Sight” and Kristin Skees’s “Close Knit,” Davis spoke to students and faculty via Zoom stating that, “when night looks like day, we have a problem…I’m not opposed to artificial light but am opposed to its callous and mindless overreach into personal space, public health, and cultural practice.”

There has been a good deal of debate within art criticism concerning how to assess the quality or success of socially engaged art.[1] Addressing the “artist as activist” impulse, now common in contemporary practice, senior art critic for New York Magazine, Jerry Saltz, stated that, “making your art about good causes does not make your work good.”[2] After experiencing Davis’s work in person, I can attest that “No Dark in Sight” is successful in both its socially conscious intent and artistic value. The viewing experience is one of internal tension created between the activist and aesthetic merits of the series. Davis’s thoughtfully composed images of artificial light and the polychrome traces it burns into the landscape, draw the viewer in, enticing them to investigate this unnatural light, not unlike the transfixed nocturnal insects the artist has documented in this series. The formal beauty of these records of light often belies their danger. Davis helps break this spell with the titles of each work, which specify the location and provide a time stamp of when the image was captured. For example, “Flood Light” features as massive concrete dam in Boulder City, Nevada. The glow emanating from the image suggests it was taken at dawn or dust, however, the time stamp corrects the viewer: 10:12pm, well after the sun has crossed over the horizon, illustrating the extent of light pollution at this location.

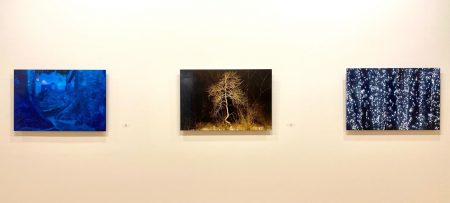

From left to right: Oil and Water – Kalamazoo, Michigan, December, 6:58 pm (2018), Flood Light – Boulder City, Nevada, March, 10:12 pm (2018), Novus Ordo Seclorum (New Order for the Ages) – Kalamazoo, Michigan, October, 11:20 pm (2016). Installation in the Alexander Brest Gallery on Jacksonville University’s campus. Image taken by the author.

Through his travels, Davis offers evidence of the multitude of ways artificial light intrudes upon and disrupts the darkness of night. The photographs are arranged in groups of 3–4 in two rooms of the Alexander Brest Gallery. These groupings generate a visual rhyming of form and content, through harmonies of light, texture, color, and shape, all of which cleverly reinforces the artist’s call for a return to balance and embrace of the circadian rhythms of natural light and darkness. A particularly effective grouping of three 30 x 20-inch photographs is unified through an exploration of synthetic light’s power to transform both natural and artificial trees, formally balanced by the contrast of blue and gold light.

In “Safe Space,” the first of the three prints, the viewer is presented with the eerie-blue, nocturnal light of a zoo enclosure after closing. The red letters of a neon exit sign are reflected on the glass of this contrived diorama, seemingly taunting the unidentified species preserved within this space, forever confined to an existence within a synthetic environment under artificial lights. “Basswood,” is at the center of this triptych featuring the twisted trunk of a wiry tree. The warped trunk and naked branches are spot lit in white gold from the forest behind it, leading the viewer to presume that this unfortunate tree finds itself at the edge of a florescent lit parking lot. The basswood tree’s serpentine trunk divulges its history within this environment, a battle during its maturation between seasonal sunlight and the nightly glare of florescent light, which has left it disfigured but resilient. The last of these prints, “Holiday Wrapping,” is a dizzying image of tree trunks concentrically wrapped in blue string lights. The thousands of blue incandescent lights creates a disorienting kaleidoscope effect, which the viewer is compelled to visually untangle and make sense of as the tree trunks move back and forth in space. Davis’s series is almost entirely devoid of human figures, appearing only as faint suggestions in shadows or reflections. This absence evokes a post-human, apocalyptic environment, which leads to the question: who is all this light for? Who benefits and who suffers on account of this unnatural light?

From left to right: Safe Space – Cincinnati, December, 10:18 pm (2016), Basswood Kalamazoo – Michigan, March, 5:35 a.m. (2018), Holiday Wrapping – Cincinnati, December, 9:18 pm (2016). Installation in the Alexander Brest Gallery on Jacksonville University’s campus. Image taken by the author.

Historically, Davis is one of many artists who have been inspired to communicate their epoch’s relationship with man-made light. In western culture, light has often been equated truth, virtue, and knowledge as illustrated in Joseph Wright of Derby’s painting, A Philosopher Lecturing on the Orrery. Here, the glow of a candle lamp, placed at the center of an astronomical model representing the Sun, is equated with the intellectual awaking and scientific revolution of the Enlightenment. After the invention of electricity and widespread adoption of incandescent bulbs, artifical light came to symbolize safety, modernization, and progress. Giacomo Balla’s canvas, Street Light, exemplifies the mechanical worshiping Futurists’ glorified perception of an electric lamp that chokes out the crescent moon behind, but also the prevailing attitude and general embrace of technology during the early twentieth century.

Joseph Wright of Derby, A Philosopher Giving a Lecture on an Orrery, in which a Lamp is put in the Place of the Sun, 1766. Derby Museum and Art Gallery, England.

Giacomo Balla, Street Light, 1910-1911. Museum of Modern Art, NY.

The elimination of artificial light is not realistic, nor is it Davis’s goal. As he stated to those in attendance at the gallery opening, he is not “anti-light,” rather, is invested in practicing sustainable ways of consuming and creating in a medium that necessitates light. He recognizes that since the early twentieth century, the largely uncritical acceptance and proliferation of artificial light, under the pretense of safety and progress, has gone too far. Davis admits, “I now realize we live in the false promise of a post-industrial revolution– immersed by inventions that dismantle the biosphere.”

Davis’s assessment is supported by the disastrous increase of dead migratory birds, who are distracted by light pollution. Recently, after collecting the bodies of 226 migratory birds that struck the building the previous night, Melissa Breyer, volunteer with “Project Safe Flight,” pleaded with the management of the World Trade Center. Breyer wrote in a Twitter post, “Lights can be turned off, windows can be treated. Please do something!”[3]

Similarly, “No Dark in Sight” is a call to action and introspection. Each of the contemplative images in this series makes visual the pernicious power of synthetic light to alter the landscape and impose ecological imbalance. The intention is consciousness raising, yet the strength of Davis’s work is that in presenting what is a critical social and environmental issue, the message is not heavy handed or overbearing. By seeking to reconcile his own relationship with light, acknowledging that photography not just records, but often requires artificial light, Davis inspires his viewers to be equally as reflective and insist upon changes that will help restore a healthier balance between unnatural light and the regenerative power of darkness.

Bill Davis’s photographic exhibition “No Dark in Sight” is on display in the Alexander Brest Gallery on Jacksonville University’s campus now through October 11, 2021.

–Laura M. Winn, Ph.D.

[1] For example, see Claire Bishop and Grant Kester’s dialog in Artforum. Claire Bishop. “The Social Turn: Collaboration and Its Discontents,” Artforum vol. 44, no. 6 (February 2006): 178-183 followed by Grant Kester’s letter to the editor and Bishop’s reply, in Artforum vol. 44, no. 9 (May 2006): 22-23.

[2] Jerry Saltz, @jerrysaltz on Twitter (August 5, 2021). https://twitter.com/jerrysaltz/status/1423322245246640132

[3] Becky Sullivan, “Hundreds of Dead Migratory Birds in New York City Prompt Calls for Dimming Lights” National Public Radio (September 16, 2021) https://www.npr.org/2021/09/16/1038097872/new-york-dead-birds