Los Angeles County Museum of Art’s “City of Cinema: Paris 1850-1907” exhibition, places us squarely in the middle of the era. There are a handful of projections on the walls, mostly consisting of films by the famous Lumiere Brothers’ cinematographs. My favorite depicts Les Halles, the grand markets of a past Paris. Les Halles provided one of the settings to Emile Zola’s novel The Belly of Paris, which contains some of the great food writing in literature. The novel is, of course, a fiction – a story about a man who was exiled from his home after Napoleon’s coup of 1851, only to return home and have trouble maintaining work and evading public suspicion among the stalls of Les Halles. On a basic level, it is his story. It is also, however, a history of France in political flux, Parisian culinary commerce, and the unfolding modernization process. The little clip of Les Halles performs a similar function, transporting visitors into a bubble of time in which the grand food markets of Paris once hustled and bustled. The clip that follows Les Halles is introduced by a summary that tells us that it was semi-scripted, but the focus is a random person. It remarks that the line between documentary and fiction was not yet established. It’s an interesting distinction, which I’d suggest isn’t so clear. LACMA’s exhibition is interested in this grey area. It gathers paintings, posters, flipbooks, and many more visual oddities. Cinema is born in tandem with the industrial modernization process. It is both more advanced than previous art forms, and contingent on their continued existence.

Auguste and Louis Lumière, 1895

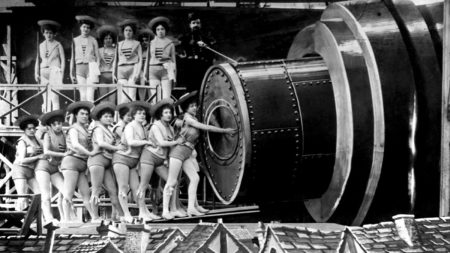

By bringing together each of the mediums that led to the origin of cinema, it becomes clear that cinema is a conglomeration of those other mediums. The exhibition reminds us that – just as cinema is an art of human assemblages – so too is it an art of productive assemblages. One sect of the exhibition, for instance, showcases a large painting of a gladiator scene. There are then next to it a handful of other depictions of the original painting. One comes in the form of an advertisement while another is a statue. Cleverly, the space juxtaposes this example with the work of Georges Méliès. Méliès was the zany early counterpart to the Lumiere Brothers. If the Lumieres gave us the ability to capture moving images, Méliès paved the way for applying it to fiction and genre experimentation. The Méliès films are a crucial example of the film as a product of painted and drawn storyboards, set pieces, statues, and advertisements. One person can create a painting, but the film image is often a modern totality of separate parts.

Some of the objects here are amusing. You might read into this history that image producers have been looking for a way to capture the moving image for ages, sometimes going to tedious and comical lengths to imitate movement. One space holds a painting of a courtyard which is illuminated by a backlight. The image demonstrates a blueprint for the imbuing of images with the element of light, such a crucial element for the capturing of the moving image. Opposite this painting sits a small collection of magic lanterns. My favorite is shaped like the Eiffel Tower, hinting at the cultural capital of the generation of images. Magic lanterns laid important groundwork for what would become slide projectors. One could input a 35 mm film slide, look through a hole and a light within would illuminate the image. These pieces inaugurate the important story of light in the history of cinema. They also, however, draw an interesting distinction. The illuminated painting is an attempt to elevate a piece of art, while the magic lantern was commonly an object of entertainment. Film almost always falls somewhere within the spectrum of art and entertainment.

Antique Magic Lantern

Throughout the exhibition we can see cinema as a medium of mediums, which fulfills an array of purposes. One might recall the now crucial writings of the Frankfurt School a few decades later. Walter Benjamin was hopeful that film could be used to organize collective power while Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer suspected it as a tool for rendering humans docile. Each analysis holds some truth, yet it has always appeared to me that when we’re talking about what cinema can do, the answer is rarely one thing or another. “City of Cinema” seeks to demonstrate this breadth of purpose and function for the moving image.

Paris, then, is the historical anchor for this expansive exploration of film. The exhibition’s introductory wall will tell you that herein marks the beginning of the great art form of our time and that Paris is indeed the beginning of this artistic birth. The city provided background via ornate architecture, winding streets, fashionable citizens, and an already rich assemblage of cultural history. The exhibition collects several different visualizations of Parisian life, including one beautiful Matisse. Many of them provide vivid, colorful visions of figures enjoying a romanticized city. Interestingly, it would be some time before film could really capture the beauty and color of some of the more expressionistic paintings of Parisian life. The influence of painted images on the film image would continue to carry weight in the development of the form.

Still from Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory, 1895

The Ronald Grant Archive

Crucially, the exhibition shows the cultural residues of the time. We’re reminded that the visual arts, cinema included, has always been a mode of interpretation and depiction. Mixed within the romanticized visions of gentile life are the murky visions guided by prejudice and racism. Another collection of Lumiere clips shows two particularly discomforting clips. One is of Native American caricatures while the other is of a company of African Americans diving into what appears to be a murky pool. The title insinuates that this is where they bath. Each clip renders the subjects as exoticized bodies, hinting at the exclusionary forces at work at the time. Within the same area there are posters and advertisements for circuses and traveling entertainment, so many of which were built on showcasing maligned subjects to ignorant audiences.

These shady social dynamics can’t be ignored while studying the traveling Lumiere cameras as well. Cinema, like so many other art forms, has ebbed along with colonialist histories. In fiction, consider the killing of natives and imperialism that occurs in Méliès films A Trip to the Moon and Robinson Crusoe, both made in 1902. Cameras traveled across the globe, capturing images of faraway cultures, a phenomenon entirely new to people who couldn’t travel at the time. These images exoticized different cultures, but they could also function as a travelogue. In some ways, the traveling Lumiere cinematographs marked the first visualization of the birth of what would rapidly become a globalized culture. Suddenly Europe was visually connected with Asia and South America. Of course, the reverberations of these early journeys can be seen all over moving images today, in ads, sports, TV and film.

A Trip to the Moon, Geoges Méliès, 1902

“City of Cinema” is fascinating as an exhibition of historicization. The early film images are particularly striking, and I suggest standing for a bit and watching them a few times over. It’s also an important story because it contextualizes so much of today’s visual culture. Indeed, contextualizing the exhibition within our present time should yield reflections on just how much groundwork was laid for the function of the medium right out of the gate. We can, of course, go to the cinema to watch blockbuster entertainment, artful independent works, documentaries, etc. We can also record bits and pieces of life on our cell phones and post them on Facebook and Tik Tok. I recorded a clip of Los Angeles’ Grand Central Market last week – the footage is not so different from the footage of Les Halles, my apparatus just happens to be more conveniently pragmatic. Televisions abound, weaving together broadcasts and advertisements, telling stories and selling products. “Cinema” as it stands is an artful medium, a commercial medium, a personal medium and a social medium just as much now, as it was at the turn of the 20th century.

“City of Cinema: Paris 1850-1907” is on view at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art through July 10, 2022

–Josh Beckelhimer