The Cincinnati Art Museum is featuring a traveling exhibition of the work of a Black photography collective formed in New York City in the early 60’s.

Olaifa and Egypt. Credit C. Daniel Dawson

The Kamoinge Workshop emerged in1963 when a Harlem-based group of black photographers came together to share friendship and technical knowledge and, most importantly, a mutual philosophy that photography could be a path to their empowerment and artistic equality. Kamoinge, pronounced kom-wean-yeh, from the Kikuyu language of Kenya meaning “a group of people acting together”, reflects the commitment of the original 14 members in support of one another as they depicted themselves and their communities as they wanted them to be perceived.

Herb Randall untitled

Their mission statement follows: “HONOR, document, preserve, and represent the history and culture of the African Diaspora with integrity and respect for humanity through the lens of Black Photographers.” To accomplish this mission, the collective, under the formative influence of Roy DeCarava, mapped out a multi-layered campaign, several aspects of which, but not all, will be touched on in this essay.

The original Kamoinge members built distinctive careers in photojournalism and commercial arenas as well as cultivating personal veins of expressive artistry and experimental directions.

The workshop itself rented a gallery in Harlem and organized exhibitions of member works. Their 1965 exhibition ”Theme Black” was attended by Henri-Cartier-Bresson, who facilitated their connection with the editors of Camera magazine, the significant international publication.

The collective orchestrated and published designed portfolios of member works, which presented how they themselves wished to be seen as artists representing their experience and their community. These were presented to institutions and art organizations to broaden awareness of their work and combat prejudicial assumptions on the quality of the African American aesthetic expression and contribution to society.

Lastly, an Annual was published to highlight the membership’s calendar year output as well as a newsletter. “Arrow” (1967) newsletter highlighted the programs carried out by membership as well as their calendar cycle of exhibitions. Several members were dedicated to teaching and mentoring youth in the photography trade. Federally funded Youth Corps helped finance teen training in all aspects of photography and technical supplies.

The photographs on view date primarily from the 60’s and 70’s, capturing the cultural shifts of the immediate community experience as well as an international component in that era.

Untitled (portrait of a boy) credit Louis Draper

The imagery is primarily B/W, emphasizing a strategic value to ‘blackness’. Choices of subject matter focused on street life, portraiture, daily work and living activities and religion. Many portrait compositions were beautiful compositions of abstract elements raising the aesthetic impact. It is interesting to note how many photographs denied access to the faces of the individuals or set the figure alone against strong light or patterned surface, adding a sense of universality and pathos.

I especially enjoyed Beuford Smith’s “Lower East Side” 1969 and Louis Draper’s portrait of a young boy against a deteriorating wall.

The Civil Rights movement of the times were a strong focus. Images of the urban black community coming out in support of Angela Davis and the March on Washington document the intersection of art, responsibility and community resistance against oppression.

2 bass hit credit Beuford Smith

The heart of the black community is in its music, especially Jazz. Musicians, singers and live performances were the subject matter of many photographers in the collective who felt it was a metaphor for photography itself. Technical expertise, timing and a sense of fluid intuition are necessary for successful expression in both art forms. Lou Draper captured iconic portraits of Jazz giants John Coltrane, Miles Davis and Charles OyamO Gordon. Herb Robinson’s photo of Mahalia Jackson captures the back of the great singer in live performance, standing at the back leg of the piano.

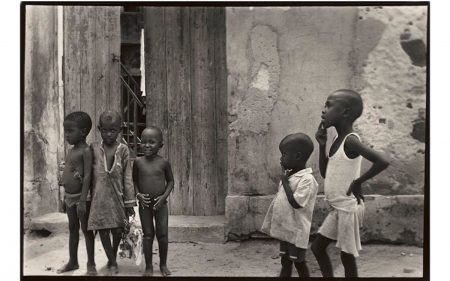

Onlookers. Credit Ming Smith

The collective’s interest included a global perspective which, in the words of Louis Draper was “the emerging African consciousness within us.” Members traveled to African countries that struggled against colonial rule and other nations with significant African diaspora communities. The peoples of Egypt, Senegal, Jamaica and Cuba were fodder for their lens and expanded their sense of an international Black community consciousness which they brought back to the United States.

Working Together is on view at the Cincinnati Art Museum through May 15, 2022

–Marlene Steele