Entering a new space is always an interesting experience. Whether it is a friend’s home or public building, you are faced with the task of conjuring up conclusions about that person or place based off of the physical elements around you – the interior structure, the smell, the reverberation in the wood as you walk across the floor. This proved to be an especially daunting task for this particular exhibition; not only was this my first visit to the gallery, but the artwork itself was made of plaster, concrete, cords, and light, making it difficult to differentiate the art from the pre-existing mechanics of the room. At times disorienting, and at others more settling, Post Fabrication (in its purest sense) is a good lesson in spatial awareness. Applying that to a commodity-based context (through the use of construction materials, processes, and practices), the artists of Post Fabrication open up dialogue specific to our understanding of labor and craft as they have been pursued in our culture.

Artist Jake Isenhour preludes the exhibition with Growth, a query of how we relate to our environment and the products that comprise it.

Shining light (literally) onto an electrical outlet, Isenhour brings attention to the physical elements of the room. A modern-day ready-made, it is both the inconsistency of function and the familiarity of the material that procures our thought. This is a key piece in the exhibition as it sets the expectation for re-thinking our tendency to consume products as instructed or dismiss them with indifference. It is a simple and equivocal call to action for the viewer – a playful herald, if you will.

IKEA – this has to relate somehow

Perhaps it was due in part to my recent trip to the land of furnishings and fixtures, but I just couldn’t shake the looming presence of the Swedish enterprise while walking around the gallery. Or perhaps it had more to do with Benjamin White’s 85321.

Benjamin White, 85321, Edition 2 of 2, 2015.

Materials: Non-shrink grout (mortar) (3000-9000 psi); 1/4” Grade 30 Zinc-Plated Proof Coil Steel Chain (working load limit 1250 lbs); 0.063” 1×19 Galvanized Steel Aircraft Cable (breaking strength 500 lbs); 3” x 3” x 1/8” steel plates welded to chain ends; angle iron hangers.

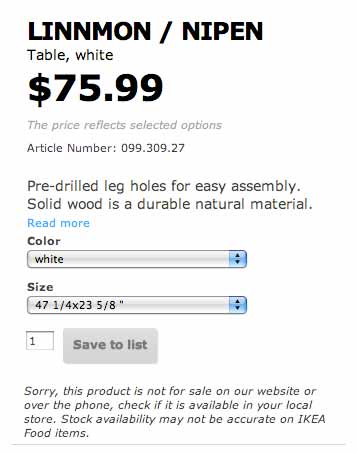

Almost as if christened by Ingvar Kamprad himself, the exposition of 85321 is starkly reminiscent of price tags gracing IKEA cacti and cabinetry worldwide. (See below)

While this work is laden with mathematic reasoning and processes galore, I am not one to tell you much about those. What I can speak to is my visceral vexation with assembling IKEA furniture and how that has everything to do with this particular work of art.

As a consumer of prefabricated products, such as the ones you get from IKEA, my relationship with the material is rooted in functionality. Bearing no responsibility other than my personal satisfaction with the product, my relationship, then, is fairly introspective. But behind products and consumer goods are people, whether by hand or manufactured, making those products. While we are brought in to the consumer mindset through references to something as innocuous as a price tag, White’s claim goes deep into our psyche.

Embedded in the framework of 85321 are notions of primal labor systems, modern class practices, and hierarchical leniencies that permeate the workforce and marketplace at large. We see this in the ascending grout and steel contraptions – the way the beams emulate the progression of an ancient class system. We see this in the stale aesthetics – a face-less, human-less, presence-less thing. We see this in the back-bending and redundant process used to execute the structure – one of a learned and mastered skill. We see this in the weight of the steel – and how for many, work is not this illustrious title with a comfortable benefits package – but it is laborious and burdensome and exploiting. We see this in the profitability of the artwork – the way it seems (and actually is) purchasable.

Breaching socio-economic constructs and consented cultural customs, 85321 is a bold and caustic body of work. It leverages the strength of the show as a whole, lending far-reaching interchange for the recipients (the viewers) and constituents (the laborers).

We <3 Corporations (yes we do!)

With the emergence of craft beer, artisan coffee, and Etsy we see our culture trending backward. While we enjoy the convenience of pre-packaged, replicable products (thank you, Industrial Revolution) there is something inherently attractive about the quality of “home” as it pertains to the consumer demographic. The market for “hand-crafted” products far exceeds, or is at least trailing close behind, that of name brands. Fueling this trend is the ever-growing fascination with sentiment and novelty and our ability to encapsulate that into a physical object. This cultural regression is seen (but almost unnoticed) in Dana Hemenway’s Untitled (nails).

Impeccable renditions of a trite technology, Hemenway’s nails perforate the walls with simplistic audacity. Elegant and quaint, these porcelain protrusions are beautiful iterations of a current and trending cultural conversation. The makers of today hold great contempt for corporations and mainstream faculties; everything is local, everything is craft, everything is made by your grandmother’s grandmother. But if you look into the history of some of our country’s largest corporations, you’ll find that at the offset of these endeavors are people who are (or were) not too different from the artificer of today. They were entrepreneurs and craftsmen who envisioned a higher quality of life fueled by the same sentiments of skill and novelty. The only differentiating qualities now are time, profit, and scale. Hemenway takes us there to that sobering and cyclical moment through a subtle but glorified version of something elemental and banal.

The consumer industry is complex. It exists as both the recipient and perpetuator of some of our culture’s chief plights. It is teeming with philanthropy while also seeping with greed. It is both the provision and thief of our society’s welfare. It is the best-kept conspiracy while at the same time completely arbitrary.

To decipher this Post Fabricated world for yourself, visit Wave Pool Gallery at 2940 Colerain Ave., Cincinnati, OH 45225.

Work is on display through April 25th.

–Hannah Leow