An artist, says artist Cole Carothers, must be patient and inquisitive. Carothers has been a working artist since the 1970s so speaks from experience. For his own paintings and prints, he says it’s a matter of simplifying, simplifying, pushing toward “a reduction of elements, simplicity of masses, trees becoming shapes.”

What is happening here is that an artist, trained when Abstract Expressionism ruled the art schools, in his own work turns to representational depiction and makes abstraction an ingredient but not the reason for being.

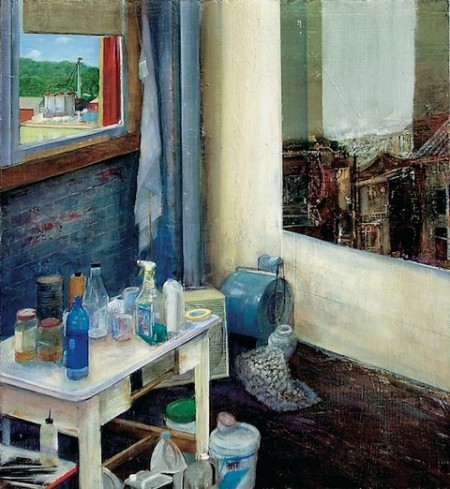

Carothers’ paintings pull the viewer in, are not quite literal so produce the feel of fiction, of stories not yet completed. Windows have been a frequent element although he’s not using them as often just now. He says they are “a way for art to take you to different places” and was drawn by the way other artists used them and their metaphysical suggestion of “inside and outside, imagined realities and their combining structural internal space.” A particularly fanciful use of window is seen in “Fans” (2003) with its table-full of painting materials beneath an open window looking out at a rural scene and a mirror on an adjoining wall, reflecting a very different, citified view from an unseen window. This work is oil on wood and is 24 inches by 22 inches.

Asked about the diminishing use of windows in his compositions he says “I think it’s a confluence of less dynamic vistas in my current studio, at ground level, and a need for change. For most of my painting career, my studios were third floor spaces with great urban views. I feel I’ve done enough of them and believe it’s a good idea to move on.”

He has a craftsman’s interest in materials, dating back to high school when “I got my hands dirty with materials,” clearly an enjoyable, learning experience. He likes traditional materials, likes to mix and make them himself, his own ground glue, his own gesso. “Acrylic dries too fast for me,” he says, and is afraid that young artists are using materials that may not last.

His own use of mixed materials is long standing. “Liquid Air” (1993), its interesting composition taking the viewer’s eye from an orange in almost center foreground across a courtyard, through a doorway and into a landscape beyond, is oil, water putty on wood. The work is square, 14 inches by 14 inches.

Carothers is Cincinnati-born, received his bachelor of arts degree from Colorado College and a master’s in fine arts from American University in Washington D.C. Like many artists he has done his share of teaching, at the Art Academy of Cincinnati and in the University of Cincinnati’s College of Design, Architecture, Art and Planning. He was also program director for Covington’s Baker Hunt Arts and Cultural Center for several years and took on other jobs (managing parking arrangements, for instance) at other times as necessity dictated.

Now, with their three daughters off on their own, he and his wife continue to live in the pleasant family house in Milford. Carothers’ paintings are on the walls, but so are the works of artist friends. Emil Robinson is there, also Kevin Muente, and in the kitchen three tiny, square paintings by a younger artist, Rob Anderson, each with a single subject – a tennis ball is one – lovingly depicted. The two family cars are parked outside at all times, as the garage is Carothers’ studio.

“The studio is the artist’s home,” he says, and finds a chair for me in his studio’s pleasant disarray. Another long time studio location for him was on Court Street in downtown Cincinnati in the 1980’s, during much of the time he was teaching at U.C. This one, a few steps from the house, is wholly convenient. It’s filled with artists’ clutter to the outside eye but very likely organized to the artist himself. The light is diffused but clear, shadows few. There are saws, needed to cut panels to whatever size a particular work requires. Tables have metal tops, he points out, and paint can be mixed on them.

He has had another studio, in northern Michigan, since he came across a farm house for sale at the end of the season three years ago. He’s been working there off and on since; the light is extraordinarily clear, not humid, and escapes urban light pollution.

Carothers likes change, likes trying different materials. Panels, at one time his usual base for paintings, are currently replaced by canvas. A relatively recent example is the landscape “Drive By Whiteout” (2011), 36 inches by 48 inches, oil on canvas. Paint dries more slowly on canvas, he says. This can be a painterly advantage. He is in no way committed to a particular size for his works, using the square perhaps more frequently than many artists but employing vertical and horizontal compositions as well.

Despite the frequency of landscapes in his oeuvre Carothers is not an outside painter. These compositions are processed in his mind from actual observance, frequently noted by camera. Asked about a specific scene which seemed to me must have been observed he said “I was traveling and my camera served as my sketchbook. I’m too impatient to stop and draw. I want to see as much as I can.” Artists tend to look with the expansive satisfaction gluttons reserve for food. He does occasionally work in watercolor out of doors, but not in oil. “I rely upon memory, revisiting a motif, and photos much of the time. I admire Antonio Lopez-Garcia for his ability to work outdoors. I tried it once in the dead of winter in Massachusetts and the experience wasn’t so great. It would be nice to take more time, and I know the quality of the effort would be significant, but I’m a pragmatist on the run.”

An interview with an artist is expected to include questions about his or her admired artists from the past and the present. I neglected to ask when in the studio, too caught up at the time with Carothers’ own work, but a later email brought a generous response that indicates how carefully and appreciatively he looks at the work of others. His response for historical artists:

“Too many to list but here are the persistent winners: Giotto, Petrus Christus, Vermeer, Goya, Villard, Bonnard, Morandi, Stanley Spencer, Diebenkorn, Fairfield Porter, Alice Neel, Gregory Gillespie, Lucien Freud. I’d say this group speaks for itself. They’re all great painters and I love the way they move the paint.”

Lopez-Garcia, mentioned above for his persistence in working out of doors, makes the list for contemporary artists, along with “Vincent Desiderio, David Hockney, Rackstraw Downes, Matteo Massagrande, Peter Doig, Ruprecht von Kaufmann, Amer Kobaslija, Eleanor Ray and Avigdor Ariko.” Ariko, not on the original list, was added by an email asking that he be included and saying that his work was first seen by Carothers in a retrospective at the Corcoran in Washington D.C. in 1978. Artists have long memories for what interests them.

I also asked about regional artists, but got this reply: “There’s such a range in expression that I won’t pick favorites. I have tremendous respect for all the artists here because in this region it’s not an easy road to stick with. I’m impressed by the diversity and talent in many younger artists, too.”

A craftsman moves on, Carothers says. He finds his work has grown “less fussy, more spontaneous. I’m currently trying to collect myself, see where the work is going.” I am among those also interested in seeing where his work might go.