When you walk into “UNRAVELED: Textiles Reconsidered” at the Contemporary Arts Center, the first piece you encounter is Legacies, 2006, by Kari Steihaug (b. 1962, Norway; resides Oslo). With an unfinished sweater hanging high overhead, it dominates the gallery and is the perfect way to start the show visually and intellectually. It succinctly illustrates curator Kate Bonansinga’s thesis: “The artists in ‘Unraveled: Textiles Reconsidered’ repurpose cloth and transform its message.” 1

For Legacies, Bonansinga, director of the School of Art, University of Cincinnati, recounts that Steihaug “gathered 70 pieces of knitted clothing from friends, family members, and flea markets. She unraveled the garments and wound all of the yarn remnants onto (wooden) bobbins, and partially knitted a new sweater from them.”

The artist also clearly articulates her intent: “Worn out knitted garments are like layers of time . . . I want to give concrete visual form to the relation between destruction and new creation, and the transition from one form to another.”

The piece is somber as she’s chosen a palette of dark brown, blush, white, silver, and burnished metallic yarns that include ordinary four-ply, fuzzy mohair, yarns shot through with Lurex, etc. Had she used brightly colored yarns, the effect would have been a cacophony of clashing colors rather than the meditative mood that Legacies evokes so successfully.

The less imposing Trousers, 2006, by Hildur Bjarnadottir (b. 1969, Reykjavik, Iceland; resides Reykjavik) is equally moving. She has unraveled a pair of her grandmother’s trousers and rolled the thread into a ball, somewhat larger than a softball. It recalls Jackie Winsor’s pieces where the sculptor obsessively wound twine into large bundles.2 “In the action of ‘reducing’ this garment to its original material the artist remembers and memorializes her loved one,” writes Bonansinga.

In Dawn, 2016, Adrian Esparza (b. 1970, El Paso, TX; resides El Paso) has also deconstructed a garment by pulling a single thread from a royal blue, teal, turquoise, denim, white, and black sarape (blanket); what’s left hangs on the wall. The title comes from the Cincinnati-based Procter and Gambles dishwashing liquid, which the artist remembers fondly from childhood. It also implies beginnings, even though the piece was directly inspired by a 1908 photograph of the Mt. Adams Incline, which opened in1872 and ceased operation in 1948.

Esparza has wound the thread tightly around evenly spaced white-headed pins nailed into narrow strips of wood, which he’s arranged in hard-edged geometric shapes. The effect is that of a Sol LeWitt wall drawing made marginally more physical, and its illusion of three-dimensionality is reminiscent of Al Held’s paintings.

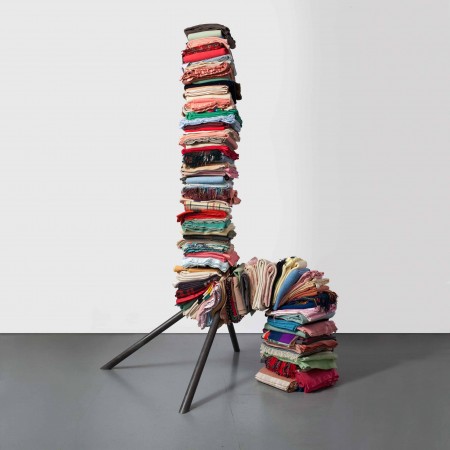

Marie Watt, Blanket Stories: Beacon, Marker, and Ohi-yo, 2016, steel armature and reclaimed blankets

Blankets are also the medium that Marie Watt (b. 1967, Seattle; resides Portland, OR) chose to work with. Sharing space with Legacies, a stack of folded multi-colored blankets is speared on a steel armature. Entitled Blanket Stories: Beacon, Marker, and Ohi-yo, 2016, it towers over visitors. Elsewhere it would have commanded the space except here Legacies flies higher and, frankly, is a more engaging piece.

The totem of previously owned blankets turns 90o and then another 90o to rest on the floor, like an arm bent at the elbow; it references marker trees made by Native Americans who bent saplings to make unnatural shapes that were signposts. Watt, a member of the Seneca tribe, connects the trees with textiles, saying, “This perseverance and fragility could be a metaphor for the behavior of cloth and our relationship to it.”

Another artist who starts from a quite recognizable textile is Noel W. Anderson (b. 1981, Louisville, KY; resides Cincinnati). In Black Past-iche (to be looked at farandaway), 2015, he’s used a floral area rug salvaged from a dumpster as the base for a collage of ephemera, but only after the rug covered his studio floor for months.

Anderson, who teaches printmaking at U. C., is African-American and much of his art addresses black masculinity. He focuses “on African American males because I am one. I am not satisfied with what I see in the world in terms of the limited vision of what African American men are or are supposed to be. I want to encourage new, more diverse visions of what it can mean to be an African American man.” 3

In Black Past-iche Anderson has collaged a page from Ebony magazine, a silkscreen of another Ebony page, a crumpled t-shirt as well as a Pepto-Bismol-pink patch onto the rug.

Bonansinga suggests that the artist’s use of “‘castoffs’ both animate beings that suffer from rejection or exclusion due to their race, and inanimate objects such as magazines and rugs that have been discarded.”

I find this Anderson piece weak, both formally and in terms of communicating a message. His tapestries are stronger, especially one where he’s made a portrait by combining the features of John F. Kennedy, Martin Luther King Jr., and the Reverend Al Sharpton. There are also his works starring the cartoon character Fat Albert, “who served to shape and define attitudes of black masculinity for generations,” according to M. B. Reilly. 4

In Convenience, 2014, Ying Kit Chan (b. Hong Kong; resides, Louisville) addresses the African-American experience even more obliquely. He writes, “Textile production, when traced back in history, is intertwined with colonialism and slavery.” Celene Hawkins’ Ode to Cotton chandelier in the 2013 “Wounded Home” exhibition at the Lloyd Library and Museum tackles the same theme far more eloquently. 5

I prefer Bonansinga’s take on Chan’s piece composed of bed sheets, stiffened with gesso and acrylic paint, which are cut and torn to make the large-scale Chinese characters that are installed on the wall. Her view is that “a bedcover reserved for privacy and intimacy becomes a public statement due to its scale, vertical orientation, and open access.” Regardless of how viewers interpret the piece, everyone can appreciate the bold effect of the graphic black abstract forms as they do Bjarnadottir’s Drawings, 2016. She has stiffened doilies bought on ebay with graphite, giving them a steely grey cast, and mounted them on white grounds. 1025

Unlike Anderson who tries to endow his pieces with meaning with what he pastes onto the textile ground, Mark R. Smith (b. 1958, Salem, OR; resides Portland, OR) aims for a very different effect when he collages textiles onto felt. In Peninsular, 2015, sections of striped cloth are butted up against each other to create geometric forms that remind me of circuit boards. He says he turned to textiles to make “ego-less paintings.” (I don’t think ego can be banished from any artwork. Even in selecting fluorescent tubes off the shelf, Dan Flavin still imbued his installations with ego. The same can be said of Carl Andre when he ordered metal plates cut to his specifications at a factory.)

Smith’s work comes a tad too close to works produced by artists using the traditional craft materials (glass, clay, metal, wood, and fiber) who make something that could be done much more easily in another medium. Here I think there might be an added wrinkle because making these hard-edged images in paint would likely be an even more laborious process than the one he’s chosen.

Bonansinga correctly says Smith’s work references quilts in structure and abstract paintings in composition. But there is nothing earth-shattering here as the art world long ago recognized a relationship between abstract painting and quilts such as those made by the Shakers and the Gee’s Bend makers (both have been accorded museum exhibitions), and other traditional quilters.

Margarita Cabrera, Saguaro, 2010, Border Patrol uniform fabric, thread, vinyl, wire, foam, and terra cotta pot

Margarita Cabrera’s (b. 1973, Monterrey, Mexico; resides El Paso, TX) series “Space in Between” uses Border Patrol uniform fabric for her sculptures of cacti found in the American Southwest. She had Mexican migrants embroider images personal to them onto the cloth, which she stretches over wire and foam to make the succulents’ branches. It all adds up to a powerful comment on the crisis at the border while also creating an arresting (pardon the pun) installation.

Bonansinga identifies Lisa Anne Auerbach (b. 1967, Ann Arbor, MI; resides Los Angeles) as the only artist “who does not reuse cloth. Instead, text is the material and subject matter for her objectification of words.” This is backed up by the artist’s own words: I “was interested in the way that text worked differently when it was what made up the structure of the fabric, as opposed to being put on top of it later . . . text is part of ‘textile.’”

Auerbach utilizes a knitting machine with designs engineered in Photoshop to create allover patterns of fortune-cookie-like strips in the works shown here. In #HASHING IT OUT, 2014, she uses hash-tag-style phrases, such as “#STAY OUT OF POLITICS,” “#TRUE BLOOD BINGE,” and “#LOVE TO WATCH.” It is impossible to see these works without thinking of Jenny Holzer, first because of the pithy sayings but also because both Holzer and Auerbach express themselves through technologies borrowed from commercial applications.

Bonansinga covers a lot of territory in “Unraveled” to produce a thought-provoking and visually satisfying exhibition.

–Karen S. Chambers

1 All quotes by Bonansinga and the artists come from a gallery brochure or wall labels.

2 In an undated interview by Whitney Chadwick for Oxford Art Online (oxfordartonline.com), Winsor explains how she began making her obsessive sculptures: “When I was first making sculpture, I just dove in and made full-scale sculpture right off the bat with no transition from being a painter. As a painter I was very interested in drawing, so when I was working on sculptural shapes I was thinking of them as drawings, you know: a line goes around and around and around and around. Part of how I thought of these early pieces is you just make the form full and fatter and fatter and fatter until you’ve built a shape . . . ”

3 M. B. Reilly, “From Fat Albert to O.J. Simpson, UC Artist Explores African American Masculinity in New York Exhibit,” UC News, September 8, 2013.

4 _________, “New Faculty Member Making His Mark in DAAP’s Print Making Program,” UC News, December 22, 2012.

5 “Celene Hawkins’ Ode to Cotton chandelier is, as she confesses “in your face.” Using a familiar form, a lighting fixture appropriate to a parlor’s décor, it is pleasing to the eye as an object, but delivers a strong message. It is the most successful work in the show by my estimation.

Hawkins was inspired by the following passage from D. A. Tomkins’ Cotton and Cotton Oil:

The white man loves to control and loves the person willing to be controlled by him. The Negro readily submits to the master hand, admires, and even loves it. Left to his own resources and free to act as his mind or emotions dictate, no man can foresay what he is liable to do.

This was written in 1901, decades after the end of the Civil War, and Hawkins found it “deeply disturbing,” spurring her to learn more how the South’s economy was built and sustained by slaves.

The symbolism of the individual parts (most cast bronze) of the chandelier is as obvious as Ghosn’s. The bulbs are semi-translucent white glass blown in the shape of the cotton boll; it has burst open, leaving parts of the golden “husk” that once contained it. They are at the ends of elegantly curving “stems,” with what look like caterpillars crawling on them. At the bottom of the chandelier are green bolls in the clutches of boll weevils. The canopy, which covers the connection to the ceiling, is a coiled whip cast in bronze.

Surrounding the center rod are female nudes with manacles on their necks and hands. The manacles are attached to delicate chains, which are draped gracefully on the arms, and end in dangling handcuffs. The women with kerchiefs, like those were worn by female slaves, lack mouths, silenced by their slave masters.

Impaled on the central rod is a lamb, representing the ancient misconception that cotton was produced by vegetal lambs. In 1350, John Mandeville wrote, “There grew there [India] a wonderful tree, which bore tiny lambs on the endes (sic) of its branches. These branches were so pliable that they bent down to allow the lambs to feed when they are hungrie (sic).”

It’s all there to see in the chandelier, but the first impression is that it is a purely decorative lighting fixture that might be found in a Victorian parlor.” Karen S. Chambers, “WOUNDED HOME, Lloyd Library and Museum,” aeqai.com, July 2013.