Aaron Skolnick’s Running Where We Stand opened Friday June 3rd at Glacier Gallery at 1107 Harrison Gallery in Cincinnati’s Brighton district. To put it lightly Skolnick is an intensely intelligent human being, both intellectually and visually, his work operating as he put it, like “a potato with many different tubers, variously intertwined.” He references, expounds, and negotiates the histories of art and civil rights under a heading of contemporaneity that is highly relative to a discourse of the margin and the tradition of history painting, both. Running Where We Stand is also incredibly timely considering the CAM’s 30 American Artists, which features 30 African American artists. The Art Academy and DAAP are also holding similar exhibitions conjunctively. Skolnick’s exhibition is of particular interest I think because he is also discussing Blackness, however through lenses of homage, history, propaganda, dissemination, and memorial. He also happens to be a white guy. The works exhibited in the exhibition effectively transfigure the act of observational drawing into a process of conversational science extruded through the boundaries of temporality and memory. It is an emblematic tour de force that pays ebullient respect and consideration to the most radical figureheads of the civil rights movement.

Glacier galleries’ Ben Bedel curated the exhibition and greeted me kindly as I entered the gallery on opening night exuding the humble pride of someone that truly cares about the artist at hand. He endeavored the scope of the show with the close cooperation of Skolnick whose studio he visited twice. Skolnick, Bedel told me, brought more work than was eventually displayed. Skolnick is obsessive, creating the same portraits over and over with incredible attention to detail. He has unified the mechanism of Warhol with the painterly consideration of Delacroix, imbuing this marriage with the reverence of memento mori and the soft white marble sculptures he became obsessed with after a visit to the sculpture garden at the MET.

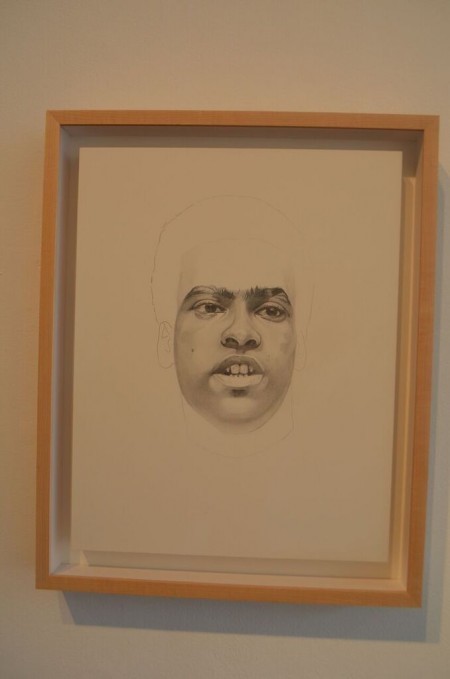

The exhibit consists mostly of portraiture featuring the figureheads of The Black Panther Party: Huey P. Newton, Angela Davis, and Kathleen Cleaver. The likenesses of radicals were executed with military attention on clay board in graphite. They are keenly concise. Sklonick’s pairing of media and substrates allows absolutely no erasure whatsoever. Considering the precision of Huey’s eyebrows, that he did not erase is incredible. The artist invested many hours into every work exhibited, describing himself as spending eight or more hours a day in the studio. He mentioned further that prior to a deadline he’ll often spends fourteen to sixteen hours daily on the work. These portraits distill the youth and meaning of these heroes while also illustrating a great tenderness in the handling of their subject. The drawings are not all portraits. His draftsmanship also covers a variety of other subjects that operate as footnotes, and further proliferations of history. Skolnick included a drawing of a banner emblazoned with a Patti Smith quote proclaiming “At heart I’m an American artist,” a drawing of a “Free Huey,” flag flying, and an image copied from a vintage Black Panther pin stating, “Free Angela.” The pin examines the dissemination of propaganda and how it affects and commodifies radical ethos into a fashion statement.

Commodity and dissemination directly inform Skolnick’s approach to history painting, and in this achieve a reflection of Warhol and the machine that debases political essence in our distracted society. Skolnick included a series of black and white paintings, and graphite drawings that depicted dog wood flowers, police dogs, Angela Davis, and a burning candle in conjunction with the clay-board drawings. The paintings and drawings that fall within this category establish a binary in the works evidenced by their pixilation and aesthetic quality of screen-printing.

The pixelation of images is one of the most interesting qualities incorporated into Skolnick’s already content heavy arsenal. Most basically, the images change as we move closer to and then further away. They are more uncomplicated up close, and appear natural from further away. This I think is a call to critical thinking. When applied to the visage of young Angela Davis, somewhat cropped, the image points to police surveillance. The pixilation of both the dogwood flowers and the candle explain the static of time, their Xeroxed quality lending a repeating prostration to a laying of alms. The dogwood flowers in one of the paintings are doubled, separated by a negative space. This formal choice especially reveals the idea of a copied image. The painterly surfaces however recapitulate the context of history painting, blending contemporaneity with centuries of painting and perspective. In this way there is a duality of mimesis.

Moving through some of the other drawings, images of riot, and the candle examine the elevation of history painting transferring memory of violent uprising in a manner that is still and yet temporally unfixed. This nostalgia is countered by the images of police dogs, of which there are several, on of which is printed as a throw blanket. The dogs arouse fear in the viewer and represent the oppressor in a manner that is violent and jarring.

The way the different works interact, traipse across time, and imitate the media of dissemination is extremely effective and as Skolnick told me quite like a potato of many tubers. Skolnick’s work is intensely mimetic. It is in mimesis that I see him dancing, wearing boots of Delacroix.

The one criticism I would offer is of the cast of characters. Wherefore art thou Emory Douglas? Douglas was the famed minister of culture for the Panther Party from ’67 until it’s disbandment in 1980. His iconic covers for The Black Panther (the party newspaper) are some of the most iconic dictums in Civil Rights imagery ever produced. They evoke the radical nature of the movement and certainly have a lot to do with zine culture and the dissemination of imagery, both themes that Skolnick has been unpacking. I briefly asked Skolnick about Douglas at the opening, wondering aloud why he wasn’t included. Skolnick’s answer more or less was that Douglas’ imagery wasn’t the kind he was specifically interested in because it transcended the nature of commodity unlike the “Free Angela,” button that he had made a drawing of. He seemed more interested in Party imagery that had been co-opted into personal identity, that figures like Angela Davis could literally be worn in this way, that this might not be wholly positive. I also could not imagine a re-handling of Douglas’ oeuvre, period. However, I think that Douglas and other prominent party members like Bobby Seale could have been represented. Then again it doesn’t seem like the message here is educational inasmuch as it might inspire the viewer to research.

Skolnick’s work is revolving and penetrative. It examines the margin from a place of respect and voyeurism that’s self-aware. The tone is conversational, specific, and rightfully grandiose. I highly recommend keeping an eye on Glaciery Gallery, Aaron Skolnick, and all their future endeavors.

–Jack Wood