The 17th edition of the “Bookworks” exhibition boasts 48 works by 30 members of the Cincinnati Book Arts Society (CBAS), which organized the non-juried show. CBAS, founded in 1998, is dedicated to “creating a spirit of community among hand workers in the book arts and those who love books.”

Aiming to showcase the most expansive definition of book, the press release ticks off nine different interpretations: altered books, pop-ups, cloth books, flag books, handmade and paste papers, conceptual books, leather bindings, accordion books, and traditional book structures that are rather rare here.

Chris Voynovich, The Knowledge of Good and Evil, 2016, embossed leather and snakeskin book cover. Photo by Patty Bertsch.

The judges–Carolyn Gutjahr, retired coordinator of the City of Cincinnati’s former grant programs for artists and arts and cultural organizations, and Aaron Cowan, Director of DAAP Galleries, University of Cincinnati–singled out one such book, awarding the Third Judges’ Award of Merit to Chris Voynovich for The Knowledge of Good and Evil, 2016. The form is familiar with an embossed leather and snakeskin book cover. That devious serpent slinks diagonally from the front to the back of the cover. The label (each object has an accompanying artist statement, ranging from the most succinct to quite expansive) reads “The Tree to be left alone,” a warning to Eve.

The execution of the binding was nicely done, but to my admittedly uneducated eye, it seemed a little pedestrian. It certainly was not a virtuosic display that might have been expected to snag the award. Clearly he was aiming to be quiet rather than bombastic. In that he succeeded.

Chairman of the Society, Judith Serling-Sturm, was honored with the Second Award of Merit with her cloth book Unarmed in America, 2016. Its message is unfortunately very apt with the recent killings of Philando Castile in St. Paul and Alton Sterling in Baton Rouge and, closer to home, that of Samuel DuBose just over a year ago. And it is also unsettling that whenever her book is seen, there are likely to be new murders making it disturbingly relevant.

The facture of Serling-Sturm’s accordion book is suitably raw. It is made of narrow linen “pages” with blanket-stitched edges. They are loosely folded together. On facing pages are childlike, South Park-ian collaged figures opposing tags of typewritten text giving the date of death and victim’s name with the location in parentheses or commentary on the statistics that she quotes in her label/statement. It starts with “21:1 that is the official statistic of the number of young unarmed black men shot by the police as contrasted with the number of young unarmed white men shot by police . . . .” The first figure is white, followed by men of color. “What I hope to do with this piece is make people really look at what this statistic means—to see each ‘unarmed’ young man as a distinct individual with his own story and to think about how—or if—that statistic affects our lives.” The result makes a powerful statement, melding content with form.

Paul Johnson, Goldilocks—The True Story, 2016, pop-up book, industrial textile dyes on watercolor paper. Photo by Patty Bertsch.

Paul Johnson, the first-place winner, strikes a very different chord with his delightful, Red Groomsian pop-up book Goldilocks The True Story, 2016. A parade of comic-strip-like panels in a confection of color (salmon, chartreuse, teal, turquoise, etc.) marches off a proscenium stage to illustrate his reimagined tale. He likes “fusing traditional story characters together and see(ing) where this leads me.” Here he’s conflated two fairy tales —Goldilocks and Three Little Pigs not three bears—broadcasting Johnson’s subversive attitude. For example, in his version Goldilocks is “a middle aged woman who spent a small fortune on cosmetic surgery.”

The accordion book format dominates; I counted 16 examples. Made of a continuous folded sheet of paper, it originated in Asia as an alternative to scrolls that were unmanageable in size. One of the most winsome here is Karen McGarry’s Within and Between. Despite its small size, McGarry has loaded it with a heavy dose of import. She explains, “There is a place that exists outside our understanding but with enough feasibility to allow us to surrender logic and rationality for potential believability and play.” Her statement continues in this vein but the title is enough to start us thinking.

The piece is charming. Two small hands, apparently plastic and maybe 2” high, are placed at either end of a wood box and are labeled left and right. They both have measuring tape “bracelets.” A folded strip of paper, six or so inches long, is looped over their middle fingers and stretches between the hands, sagging like a clothesline. “Words only reveal what is not concealed . . . ” is written on it. Whether or not I believe it, that’s a sentiment that resonates with me as a writer.

Traditional book forms are in short supply here but you shouldn’t miss Jeanne Taylor’s untitled miniature book, perhaps an 1 ½” high (told you I was bad at this). It has a marbleized cover. She explains that, “I first began by making handmade papers. Then I realized I loved the art of transforming paper to page even more.”

I wonder if all of these book artists (dreadful term) don’t feel the same way.

–Karen S. Chambers

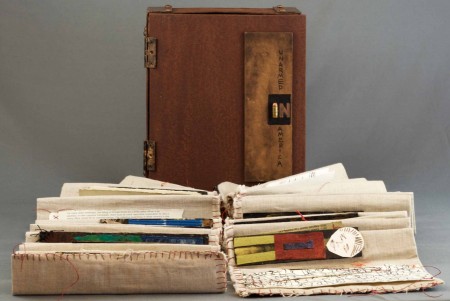

Complementing “Bookworks” is the Keith Kuhn Memorial Exhibit, a small selection of books from the Library’s own collection. It is organized annually in the memory of former Library Services Director Keith Kuhn, who directed the Library’s expansion of the collection of artists’ reimagined books.

“Bookworks XVII,” through September 4, 2016, The Public Library of Cincinnati and Hamilton County, Main Atrium, 800 Vine St., Cincinnati, OH 45202, 513-369-6900, cincinnatilibrary.org. 9 a.m.-9 p.m., Mon.-Wed.; 9 a.m.-6 p.m., Fri.-Sat.; 1 p.m.-5 p.m., Sun. Cincinnati Book Arts Society, cincinnatibookarts.org