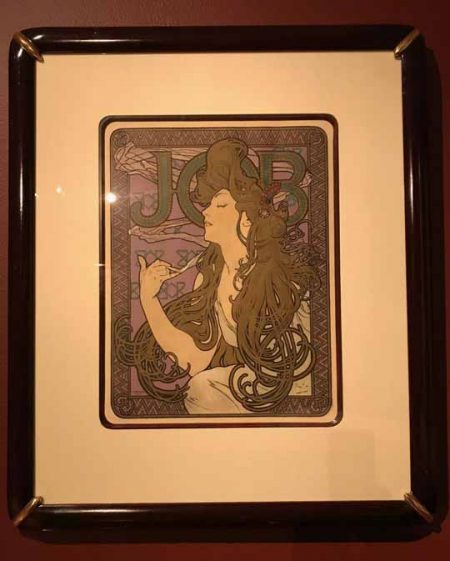

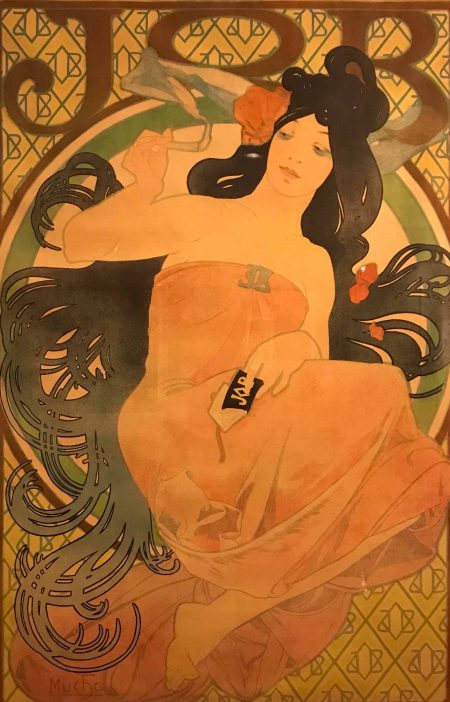

Like Impressionism, with its wild brushstrokes and look of abandon in representing the world shocked the smug Parisian Salon art community, so too, Art Noveau originally was intended to be moderne, to usher in the new century, the twentieth century. But now, oh those erotic cascades of hair in Alphonse Mucha’s women smoking in Job cigarette posters seem dreamy, decorative and safe today. But they were, in their time, anything but.

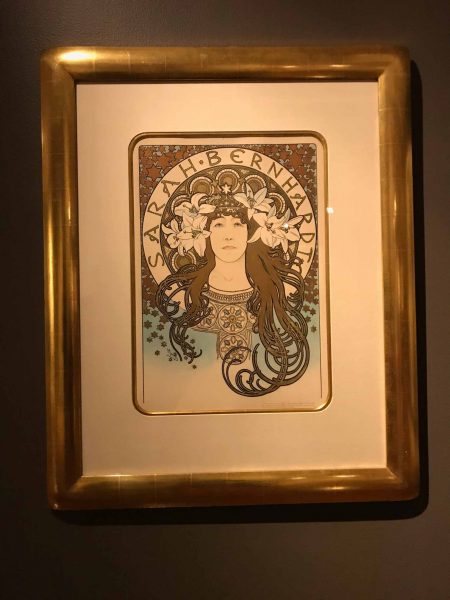

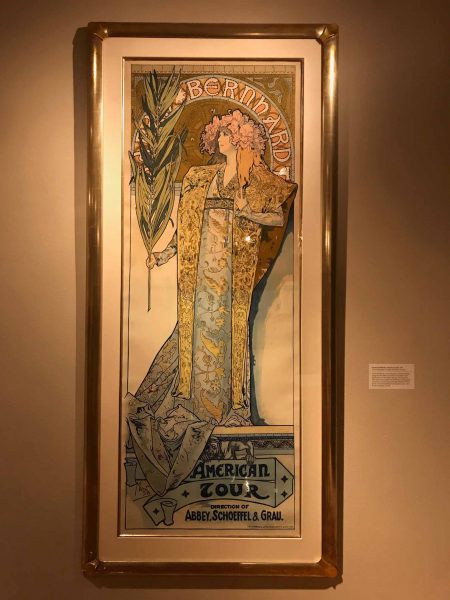

A woman smoking and loving it! A woman on a bicycle riding alone! And that sensational actress Sarah Bernhardt who contracted Mucha to publicize her! What was the world coming to? And who was Alphonse Mucha who jumped in, both hands holding pencil and brush, to usher in the consumer age? And become the globally sought-after commercial designer. What Andy Warhol was in his early years as a commercial artist, Mucha pretty much invented. Invented.

None of this talk of consumerism is to take away any of the originality, the fabulous drawing skills, compositional skills, eye for detail and color harmonies that characterize Mucha’s art and the quality of his art making. But it’s as if we think we know Mucha, since his beautiful paintings that were made into stunning large posters and beautiful illustrations for up-and-coming periodicals seems familiar to us. He invented the style, originally referred to as “the Mucha style” and it grew to become Art Noveau. Mucha basically invented Art Noveau.

It is hard to imagine someone with such an impactful vision. Since I am not a Mucha scholar and cannot discuss with you the tracking of his genius fully, I can only marvel at his originality since he seemed to be among the first to recognize the power of visual images to sell things. Think of those lovely 19th century oil paintings by Gustave Caillebotte of proper women, always dressed in black head to toe, walking down Parisian streets in pairs holding carefully in their gloved hands the wrapped items they bought. Even Gabrielle Munter, decades later, painted a cropped view of a proper woman in black with the potted geranium she purchased held carefully with gloved hands. And here’s Mucha posing the women models in his studio with their improbably luxuriant hair loose, their arms naked and in one hand….a cigarette. Oh my! And those loose robes, unbelievable. Could be Cleopatra’s private chambers. And it sold Job Cigarette papers, biscuits, bicycles.

The exhibition curator is art historian, Gabriel Weisberg, Professor Emeritus of Art History, University of Minnesota, who states in the catalog: “Mucha’s ability to understand the major creative themes of the day, to use them in the most original ways possible, and to create works of art that remain seductive for future generations, is truly his great triumph.” It is also not possible to mention all the artwork he did since his output was so vast.

The exhibition presents seventy-five dreamy and alluring works: rare, original lithographs, proofs, sketches and drawings, books, illustrations, portfolios and advertising ephemera in gallery walls that the museum painted rich deep mahogany, maroon, and cream. The presentation of the artwork in the gallery spaces envelope you with the rich colors on the wall that fully enhance Mucha’s art work. Viewers did not rush through the galleries, they lingered. The Dayton Art Institute is the sole Midwest venue for this national tour and the staff has made this a really special exhibition.

There is a lot to unravel in discovering why Mucha became so spectacularly successful. Two obvious elements of his oeuvre are first his use of nature in the form of tendrils, vines small and large bursting across the picture surface, flowers both real and imagined, floral wreaths, boughs, leaves and trees. His extensive use of arabsesques was probably part of the Orientalizing of that era in French art, painting, as East influenced West, probably via Turkey. His women are part of and engulfed in the Eden he imagined. all those arabesques from Persian art: want to mention, even if only in one sentence?

Second, and more importantly, he recognized that beautiful women sell products. If Mucha isn’t discussed in the history of graphic design, he should be. He fully embraced the femme fatale. Importantly he did not portray the modern woman as tainted, like Toulouse Lautrec did with his dance hall posters. Between World War I and II, George Grosz crudely portrayed women in brothels. Mucha would have none of this. His women were self-possessed. Look at the images of his women. They look directly at you or they are lost in thought, their own thoughts, while they smoke. These are not the wistful women looking longingly at a man – there are few men featured in Mucha’s paintings and posters. These women are happy all by themselves. While this may, in the minds of some, signal the increased objectification of women, it also signals the emancipation of women. In returning to the image of women in a standard French painting, such as the Caillebotte I mentioned where the women were locked into black head-to-toe clothing, we can see that Mucha had his finger on the pulse of modern times.

Because the women he depicted could dress and act as they wished.

Not until Mucha embarked on his monumental Slav Epic murals, which I will discuss in a moment, did he feature men prominently in his artwork. Mucha’s fame was perhaps inaugurated in representing Sarah Bernhardt in her theatrical role as Gismonda in 1894. Interestingly, when Sarah Bernhardt made her American theatrical debut in 1895, the Strobridge Lithographic Company of Cincinnati was hired to print the popular Mucha poster of her for her national tour. Bernhardt fully understood Mucha’s vision and how his visual presentations enhanced her career. As such, Mucha designed costumes and sets for her performances and was under contract with her for a number of years to make paintings of her in various roles that were then made into large, lush, full-color posters.

In discussing Mucha’s use of color, it is fully in keeping with what we think of as the Art Noveau aesthetic. There are no jarring colors such as European Kandinsky and Der Blaue Reiter group used slightly later. As did the Russian avante garde. Mucha still had one foot in the late nineteenth century even as he was firmly striding into the twentieth. Thus, his palette is nature based, serene and generally pastel. The paintings and posters are suffused with sage greens, pale blues and lavenders and a full array of cream, beige, apricot, soft corals and tan. There are few jewel tone greens, reds and blues. There are no strident colors that came slightly later in modern art or such as were seen presciently in Lautrec’s poster of a dance hall girl whose face was turquoise blue. For Mucha, most dark tones he uses are the soft black of a Job cigarette poster model’s hair or the mahogany of furniture in a room. Mostly, he positions his main characters in the center, or off-center when a space for contemplation is implied. While his paintings and posters are filled with decorative flowers, vines and designs, they are not cluttered. There are no unnecessary objects in his art works. Thus, they function brilliantly as illustrations. Gold leaf is employed to add mysticism, and luxuriousness to numerous images. It is what makes Mucha’s artwork look serene and otherworldly. Somewhere you would like to be.

I was completely unfamiliar with Mucha’s last great endeavor, his Slav Epic. Twenty large mural paintings in Prague comprise this series. Mucha worked over twenty years in the planning and execution of the series. It is represented in this exhibit in some large-scale drawings, some posters for the inauguration of the series in Prague and photographs of the paintings in situ. In this body of work, Mucha returns to a more classical style of representation, perhaps because he was not selling anything here. There was not the need to graphically illustrate the fun of relaxing and smoking. In the Slav Epic, Mucha begins with Svantovit, the god of Slav mythology, presented hauntingly with three faces fused into one, left profile, center, and right profile. In this Svantovit is the past, present and future of the Slavic people.

Knowing that Alfonse Mucha created this epic series of monumental paintings adds tremendous depth and pathos to his work. Just as many of Georgia O’Keefe’s paintings were made into posters doesn’t mean she wasn’t a hell of a modern and innovative painter just because her posters sell. Still. So Mucha, who is remembered for his powerful graphic and alluring style, was nonetheless a tireless artist who worked in an enormous range of mediums both traditional, like oil painting, as well as modern mediums, like paintings for posters and book illustrations and designs for modern products. This exhibit fully presents an extraordinary artist to a twenty-first century audience.

The Dayton Art Institute

456 Belmonte Park North, Dayton Ohio 45405

937-223-4ART (4278)

Regular Museum Hours

Wednesday – Saturday: 11:00 a.m. – 5:00 p.m.

Sunday: Noon – 5:00 p.m.

Extended hours until 8:00 p.m. on Thursdays

Closed Mondays & Tuesdays

–Cynthia Kukla is an artist and Professor Emerita of Art living in Cincinnati.