In my mind Eugène Atget (1857-1927) and Berenice Abbott (1898-1991) are intrinsically linked, like peanut butter and jelly, or, for the grownups, gin and tonic. So I was surprised when Kevin Moore, FotoFocus artistic director and curator and curator of “Paris to New York: Photographs by Eugène Atget and Berenice Abbott” at the Taft Museum of Art, noted that this exhibition pairing them was a first.

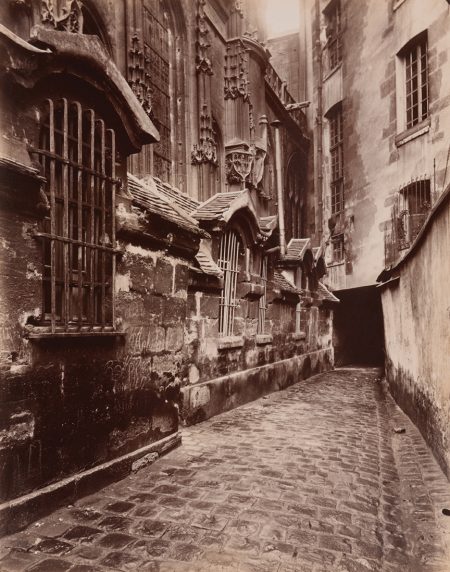

Eugène Atget, Courtyard St. Gervais and Protais (Cour St. Gervais et Protais), 1899-1900, gelatin silver chloride print, 21.5 cm x 17.2 cm. Courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art: Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Carl Zigrosser, 1968, 1968-162-32.

The relationship between Abbott and Atget was complicated. Could she be called his student since their styles and subjects were virtually identical? But by the time she met him in Paris in 1926, she had already developed a very straightforward style in her portrait work that could have been translated into her architectural photographs. But did he influence her choice of subject? Absolutely.

Abbott was the queen of PR but Atget never sought the limelight. He didn’t even wish to have his authorship of three photographs in the June 15, 1926, issue of La Révolution Surréaliste,no. 7. 1912, acknowledged, demurring by saying, “These are just documents I make.”

Abbott devoted herself to promoting Atget’s work, and then came to resent the time she might have spent producing her own.

Moore, in his essay for the exhibition’s accompanying book, ticks off some of the ways Atget and Abbott differed:

Abbott was young, open, and adventuresome; Atget was old, cautious, skeptical. She was an American and had a boundless sense of possibility; he was French and knew and respected the parameters of his society.

But one thing is clear: Abbott did want to do for New York what Atget had done for Paris.

Berenice Abbott, Newsstand,November 19, 1935, gelatin silver print, 19.1 cm x 24.3 cm. Museum of the City of New York. Gift of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1951, 51.16.15A.

Born in Springfield, Ohio, in 1898, Abbott had a talent for insinuating herself into the highest artistic circles wherever she was, even in Columbus, where she studied writing at O.S.U. in 1916. There she was part of a radical artistic community that included the actress Sue Jenkins. In 1917, Jenkins, who had moved to New York, staked Abbott to a $20 bus ticket; the Buckeye arrived penniless in the midst of a February blizzard and never regretted her decision.

In New York, Abbott was part of a crowd that included Eugene O’Neill, Edna St. Vincent Millay, Djuna Barnes, Marcel Duchamp, and Man Ray. She turned her hand to acting and sculpting as well as studying journalism at Columbia, but nothing stuck.

In 1921 she headed to Paris where she met Leo Stein, Ossip Zadkine, Jean Cocteau, Tristan Tzara, André, Marie Laurencin, Max Ernst, Peggy Guggenheim, and reconnected with Ray who would introduce her to photography and to Atget. Ray hired her as a studio assistant in 1923 with her chief qualification being a complete lack of knowledge about the medium. She didn’t begin making photographs until 1925 and quickly established a successful portrait studio, sometimes competing with Ray for clientele.

Eugène Atget, printed by Berenice Abbott, Animal Circus at the Invalides Square (Fête des Invalides), 1898 (negative), about 1930 (print), gelatin silver print, 16.5 cm x 22.7 cm. Courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art: Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Carl Zigrosser, 1968, 1968-162-34.

Atget also took a circuitous route to photography. Born in Libourne in southwest France in 1857, he moved to Paris in 1878 to study acting but gave it up because of a vocal chord infection. He tried painting before taking up the camera in 1888. He returned to Paris in 1890 and hung out his shingle: Documents pour artistes. He developed a commercially successful business selling to artists and also sold thousands of prints to the Commission Municipale du Vieux Paris and other historical archives. But the Great War impacted his business negatively, and his career never recovered.

Eugène Atget, printed by Berenice Abbott, Rue des Chantes, 1923 (negative), about 1930 (print), gelatin silver print, 21.6 cm x 17.5 cm. Courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art: 125thAnniversary Acquisition. The Lynne and Harold Honickman Gift of the Julien Levy Collection, 2001, 2001-62-342.

When Ray introduced Abbott to Atget in 1926, he was a broken man. His business had faltered, and his companion of more than 30 years, Valentine Compagnon, had just died. Abbott was unaware of his successful commercial career, but instead saw a man “slightly stooped” and “tired, sad, remote, appealing.” Taken by his photographs, she bought several and showed them in the 1928 Salon de l’Escalier, already promoting his work.

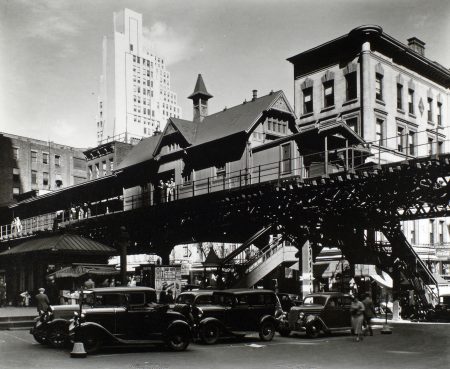

Berenice Abbott, Hanover Square,May 25, 1936, gelatin silver print, 20.3 cm x 25.4 cm. Photography Collection, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations, CNY#131.001.

After Atget’s death in 1927, Abbott set about to acquire the contents of his studio. His friend André Calmettes, director of the Théâtre Municipale of Strasbourg, had already sold 2,000 negatives to Monuments Historiques, but Abbott purchased the remaining contents of the studio–nearly 8,000 prints and 400 glass-plate negatives. Taking them back to New York in 1929, she began to promote and sell his work, aided by the budding gallerist Julien Levy.

Eugène Atget, Boulevard de Strasbourg, Corsets,1912, gelatin silver chloride print. Courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art: Gift of Carl Zigrosser, 1953. 1953-64-40.

As Atget was intent on documenting Old Paris, he also captured its popular culture, especially in his photos of storefronts. Many stylish shops lined the Boulevard de Strasbourg including this one displaying corsets on dressmakers dummies. The corsets look like instruments of torture, as I suspect they were for the ladies who were laced in in an attempt to achieve the fashionable hourglass figure. It strikes me as interesting, if not downright odd, that these undergarments, unmentionables, are displayed so boldly at a time when a glimpse of ankle was scandalous.

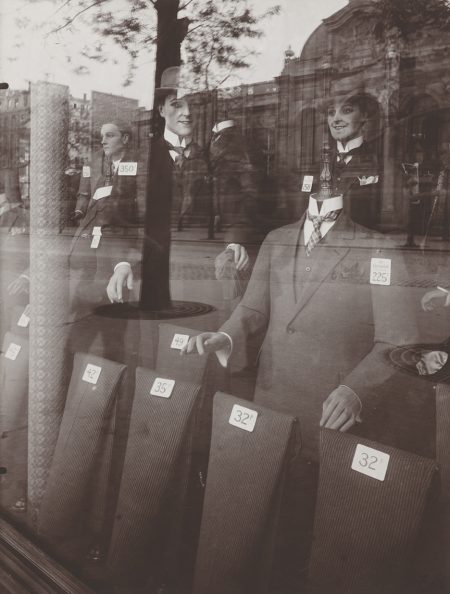

Eugène Atget, printed by Berenice Abbott, Shop, avenue des Gobelins,1925 (negative), about 1930 (print), gelatin silver print, 22.8 cm x 17.3 cm. Courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art: Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Carl Zigrosser, 1968, 1968-162-37.

Despite Atget’s protestations that his photos were “just documents I make,” there is almost always something else going on. Reflected in the window of a men’s haberdashery is the Gobelins factory, reaching farther back to the 17th-century and creating a dialogue through time.

Eugène Atget, Luxembourg Gardens—Marguerite of Provence,1901-1902, albumen silver print, 22.1 cm x 17.8 cm. Courtesy of the Philadelphia Museum of Art: 125thAnniversary Acquisition. The Lynne and Harold Honickman Gift of the Julien Levy Collection, 2001, 2001-62-145.

Nothing could be less artistic on first glance than Atget’s view of the Luxembourg Gardens. The bare trees are regimented in straight lines, and two statues of unknown personages, one perhaps a medieval queen, are seen at an angle. A man sits at the end of a park bench with his head down, possibly reading the morning newspaper. But the morning mist has not completely burned off, and the solitary figure in silhouette imparts a sense of melancholy. It is a document of the moment but also a haunting image.

When Abbott returned to New York in 1929, she planned “to do for New York what Atget did for Paris.” The project became known as Changing New York,and in her application for funding from the Federal Art Project (FAP), a part of the Farm Security Administration, best known for sending photographers, including Dorothea Lange and Walker Evans, into the American heartland to document rural poverty, she wrote that the purpose of the project was “to preserve for the future an accurate and faithful chronicle in photographs of the changing aspect of the world’s greatest metropolis.”

Abbott was in the moment and embraced change. Atget had sought out Paris before the 1789 revolution that was in danger of disappearing forever.

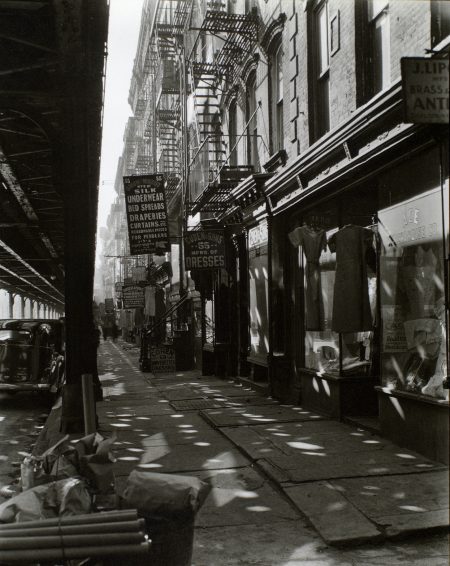

Berenice Abbott, Allen Street, #55-57, February 11, 1937, gelatin silver print, 25.4 cm x 20.3 cm. Photography Collection, Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs, The New York Public Library, Astor, Lenox and Tilden Foundations, CNY#208.002.

However, like Atget, Abbott did document what might be soon gone. Allen Street#55-57 is certainly still there, but it’s unlikely unchanged.

But there are some of Abbott’s views that still exist (or did 10 years ago when I left New York). I remember the wrought-iron doorway at 16-18 Charles Street in the West Village, and the exclusive Alwyn Court still stands at 911 Seventh Avenue.

Berenice Abbott, Bread Store,February 3, 1937, gelatin silver print, 23.5 cm x 19.1 cm. Museum of the City of New York. Gift of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1948, 89.2.2.40.

Zito’s on Bleecker was right around the corner from my apartment in the West Village; I bought my fair share of their loaves with their crunchy crust over the years. This is one slice of New York that hasn’t changed.

Berenice Abbott, South and DePeyster Streets, November 26, 1935, gelatin silver print, 22.9 cm x 18.1 cm. Museum of the City of New York. Museum Purchase with funds from the Mrs. Elon Hooker Acquisition Fund, 40.140.233.

In South and DePeyster Streets,Abbott juxtaposed old and new New York. She positioned her camera across the street from tenement buildings with a motorcar and a horse-drawn wagon parked in front; there is a street vendor in the foreground. Even though this scene occupies nearly the entire bottom half of the composition, the eye is drawn to the ghostly skyscrapers rising in the background: 60 Wall Tower and the Bank of Manhattan Building, at one time the tallest building in the world at 925 feet. It’s old New York meet new New York.

Berenice Abbott, Seventh Avenue Looking South from 35thStreet, December 5, 1935, gelatin silver print, 23.5 cm x 19.1 cm. Museum of the City of New York. Gift of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1949, 49.282.240.

Abbott captured the dynamism of the city in Seventh Avenue Looking South from 35thStreet. Dark towering buildings create a canyon that stretches into infinity. The angle emphasizes the speed of the movement of vehicles and pedestrians, both dwarfed by the structures lining the avenue. This is quite different from the human scale of Atget’s photos and of Abbott’s of a disappearing New York.

Atget and Abbott were given their own galleries, but in the final section, Moore pairs photographs with subjects that are similar in content but not composition. Perhaps the closest they come are Atget’s Ragpicker’s Hut, 1910, and Abbott’s Huts and Unemployed, West Houston and Mercer Street, October 25, 1935. Both photographers were interested in those who lived on the margins of society. The huts are shambling affairs, but both reveal a sense of individualism and pride, in a way, as these unfortunate souls have decorated them. On the French hut, the ragpickers have placed stuffed animals. The New Yorkers, victims of the Great Depression, have erected a ramshackle shelter with framed pictures for the roof. Today we might describe these hovels as folk or outsider art.

If the cliché that a picture is worth a thousand words is true, then Atget and Abbott have told the stories of their two cities eloquently.

–Karen S. Chambers

“Paris to New York: Photographs by Eugène Atget and Berenice Abbott,” The Taft Museum of Art, 316 Pike St., Cincinnati, OH 45202, 513-684-4516, taftmuseum.org. Wed.-Fri. 11 am-4 pm, Sat.-Sun. 11 am-5 pm. The Taft is closed Mondays and Tuesdays, New Year’s Day, Independence Day, Thanksgiving Day, and Christmas Day. Admission: members free; adult $10 in advance, $12 at door; senior (65+) $8 in advance, $10 at door; children (18 and younger) and military free. Sun. free. Through January 20, 2019.