Can’t you see it

Can’t you feel it

It’s all in the air

I can’t stand the pressure much longer

Somebody say a prayer

Alabama’s gotten me so upset

Tennessee made me lose my rest

And everybody knows about Mississippi goddam

-Nina Simone

In 1963, Nina Simone wrote this song in protest of the atrocities happening to African American people in the South as they fought for civil rights. In the lyrics, there’s a response to her demand for change with a refrain of caution to “do it slow” that Simone rejects with frustration, disgust, and urgency. Hearing it makes me realize how little things have changed. During her tour in 2000, three years before her passing, she was still performing this song, and if she was alive today no doubt she’d be playing it in protest of the murders of George Floyd, Breonna Taylor, Ahmaud Arbery, and so many others. It is as powerful as it is relevant today.

Link to live performance of Nina Simone singing “Mississippi Goddam”

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=LJ25-U3jNWM

No one could have predicted what kind of year 2020 would turn out to be, but eerily prescient is the 2015 documentary film by Cincinnati native April Martin and Paul Hill, “Cincinnati Goddamn”. The film explores a period of time in Cincinnati, 1995-2006, during which 15 African American men died at the hands of police. The film focuses on the Nov. 7, 2000 murder of Roger Owensby, Jr. and its subsequent legal proceedings as well as the murder of Timothy Thomas in 2001 that sparked riots that shocked the nation. Those riots led to a Justice Department investigation of the Cincinnati Police Department that resulted in a “Collaborative Agreement” with the police and community. Although that sounds like a positive outcome, no police officer involved in the aforementioned murders was convicted, and in fact the film is shocking in that it shows the absolute disregard for victims and their families within the justice system. It lays bare the seeming trivialities and banal mechanisms of law that so callously stack the deck against justice for them. At the end of the film, historian Manning Marable, seeing that justice is far from prevailing, states, “Cincinnati is a harbinger of the future. There will be more Cincinnati’s over the next decade, I promise you.”

Still from “Cincinnati Goddamn”. Police officer charged in murder explaining reason for violent treatment of Roger Owensby, Jr.

“Cincinnati Goddamn”

Link to streaming site at Wexner Center for the Arts through June 25th

https://www.wexarts.org/film-video/cincinnati-goddamn

Martin and Hill’s film, like other works of art made in response to oppression and injustice is effective because it serves as a concentrated, concrete form of what a community of people is feeling at a specific time. It also gives new audiences a way to communicate, or see reflected, their own outrage, despair, or sense of agency in light of other such injustices. Art born of protest that remains relevant captures the spirit of an issue, a movement’s energy and emotion, and puts it in a kind of aesthetic container that we can return to in later times to recall feelings and share experiences with other generations. In the US, after having suffered 400 years of racism, African American artists have taken leading roles in the creation of art born of protest. Along with Martin and Hill’s film, below are just a few important works in the form traditional studio arts, media, and public art.

Spike Lee’s 1989 independently produced feature film “Do The Right Thing” is well worth revisiting now. Lee’s story ends where “Cincinnati Goddamn” begins. It presents fictional residents of Brooklyn’s Bedford Stuyvesant neighborhood as they experience deadly police brutality and the racial tensions that lead up to it. The characters represent the complexities of a city neighborhood ecosystem, its youth and elders, its history, economic inequality, and shifting demographic, as well as its strengths, beauties, and threats to the various cultures in juxtaposition. The film is irreducible to simple assessments of individual human motivation, cultural stereotypes, structural institutions of racism, and morality; its characters variously champion philosophies of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr., Malcolm X, white supremacist ideologies, or conventional platitudes about freedom and power. At the time it was made, the film was dedicated to the families of Eleanor Bumpers, Michael Griffith, Arthur Miller, Edmund Perry, Yvonne Smallwood, and Michael Stewart, people who were murdered by police. Lee has recently released a brief video that shows the fictional murder of his character Radio Raheem at the hands of police edited into the widely shared videos documenting the murders of George Floyd and Eric Garner.

Link to Lee’s brief recent video

https://www.instagram.com/tv/CA38-qJD-qd/?utm_source=ig_embed

A generation before Lee, and two before Martin and Hill, African American women studio-based artists created iconic works inspired by the Civil Rights and Women’s Movement protests of the 1960’s and 70’s. Many went on to found or participate in organizations to fight for inclusion and continue protesting injustices. Faith Ringgold’s large-scale work “American People Series #20: Die,” from 1967, was itself inspired by the painting of an East St. Louis race riot, Panel #52, in Jacob Lawrence’s Migration Series from 1940-41, as well as Picasso’s 1937 painting Guernica, made in response to a Nazi bombing of Basque civilians during the Spanish Civil War. Ringgold’s work went unappreciated for many years, but now hangs at New York’s MOMA directly adjacent to Guernica. The piece depicts a group of figures, repeated as if we are watching a time lapse: men and women, black and white, children and adults, in the midst of a riot, their faces filled with terror and their clothes, in fact the whole canvas, is strewn with streaks and blobs of blood red paint. Ringgold, an outspoken artist as well as teacher, author and activist, in 1968 co-founded the Ad Hoc Women’s Art Committee in protest of an exhibition at the Whitney Museum of American Art that included no women and no African American artists. Later, she cofounded Women Students and Artists for Black Art Liberation, the National Black Feminist Organization, and “Where We At” Black Women Artists.

Caption: Link to Phillips Collection images of The Migration Series by Jacob Lawrence

A live Q&A will happen here on June 18th https://www.moma.org/calendar/events/6674

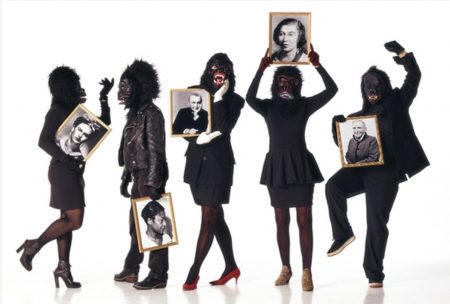

The recently deceased painter Emma Amos, a graduate of Antioch College in Yellow Springs, was the only female member of the African American artist group Spiral, a short-lived but influential African American artists’ collective formed as a response to the 1963 March on Washington. Her paintings consist of figures in the midst of abstract spaces where appropriation, symbolism and use of color and pattern layer political meaning that addresses race, class, and sex bias in the art world as well as the broader societal realm. In the piece “Work Suit” she applies a photo transfer of the nude self-portrait of white European painter Lucien Freud to the painting of her own body, with her own head and feet clad with shoes, as she looks down on a white nude model. Amos was an activist for the majority of her career, becoming involved in the women’s movement as an editor of the 1970’s feminist art magazine Heresies, and in the 1980’s as a member of the Guerilla Girls (under the pseudonym Zora Neale Hurston).

The assassination of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. in 1968 and the Los Angeles Watts Riots in 1965 compelled Betye Saar to redirect her art in response to violent racism. Saar was politically active in black nationalist and black feminist circles, although she never officially belonged to one particular group. However, much has been written about the role Saar’s 1972 work of assemblage “The Liberation of Aunt Jemima” has played in the history of American art and politics. In 2007, Angela Davis said that the Black Women’s Movement started with this work that appropriates the racist caricature of Aunt Jemima and recasts her as a revolutionary heroine, posing with a broom and a rifle. In another work from the series, “Liberation of Aunt Jemima: Cocktail”, the face of Aunt Jemima on a wine bottle makes a Molotov cocktail, stuffed with a wick made from the checkered rag used to tie back her hair.

Contemporary artists have effectively used site specific installation in the public realm to draw attention to racial injustices. Recent works operating in this space have drawn significant media attention, raising the profile of the work of art and its challenge to oppressive ideologies. Hank Willis Thomas, whose conceptually based works in a variety of media address themes of identity, media and popular culture, co-founded the organization “For Freedoms” in 2016 in order to “use art to deepen discussions on civic issues and core values” and “deepen public explorations of freedom in the 21st century” according to the group’s mission statement. The name refers to the Norman Rockwell paintings of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s “Four Freedoms”, freedom of speech, freedom of worship, freedom from want, and freedom from fear. For Freedoms has hosted gallery exhibitions, conferences and public art, such as billboards and other electronic signage. Prior to the 2016 election, the organization posted billboards featuring a 1965 image from Bloody Sunday when police brutalized peaceful civil rights protesters in Selma, Alabama. The billboards included the words, “Make America Great Again”. The image shows activists John Lewis, Hosea Williams, Albert Turner and Bob Mants facing down a group of state troopers, moments before the violence begins. The message unintentionally created a great deal of public confusion over the billboard’s intent – either a blatant promotion of white supremacy or a cynical call-out of Trump’s racist platform – but as a result generated much publicity and public discussion.

Dread Scott became the subject of a national conversation about freedom and art in 1989 for his piece, “What Is The Proper Way…?” which required viewers to walk on an American flag placed on the floor in order to view photographs of flags draped over coffins and a flag burning protest. Mounted on a wall below the images was a notebook where viewers could write their response to the question. President George H.W. Bush called the work ”a disgrace” and Congress moved to create a law fining anyone who displayed the American flag on the ground. Scott’s 2016 work, “A Man Was Lynched by Police Yesterday”, displayed in an early Four Freedoms exhibition at Jack Shainman gallery in 2016, was created as a result of the murder of Walter Scott in 2015. The work consists of a flag designed as a reference to flags flown by the NAACP from their office in New York in the 1920’s and 30’s the day after an African American was lynched in the U.S. Dread Scott continues to create works that challenge structures of American politics, economics, and governance. In November of 2019, his work “Slave Rebellion Reenactment” involved organizing hundreds of people in a reenactment of the largest slave revolt in U.S. history in 1811. The project took place in Louisiana, where costumed and armed participants retraced the steps of the rebellion, marching 26 miles over two days from the outskirts of New Orleans to Congo Square.

Link to video:

https://www.youtube.com/watch?time_continue=29&v=v2to3S0iabE&feature=emb_title

The current Black Lives Matter protests over recent police killings of African Americans have resulted in striking creative expressions of outrage and empathy, both temporary and permanent. Murals have been painted around the world, graphic protest designs proliferate, and communities have reassigned or appropriated public artworks, such as the Monument to Joe Louis, a.k.a. the “Joe Louis Fist” as a platform for protesters in Detroit, the toppling of the statue of slave trader Edward Colston in Bristol, UK, and the “Serve and Protect” hands sculpture doused with red paint outside of a police station in Salt Lake City. It remains to be seen how artists will interpret these murders and protests over time, what tools they will use, what form their art will take. As protest participants, and later as audiences, people will inevitably seek out works of art to help us comprehend and commemorate the moment we are experiencing right now. Let us hope that we will not find ourselves needing to repeat these same protestations again as the next generation rises.

–Susan Byrnes