In the 18th and 19th centuries, there was a popular genre of fiction known as “It-Narratives” or “Novels of Circulation,” which told their stories in the voice of some object which passes through many hands. Some of the earliest of these began with money (the story, say, of a bank note): the genre spread to all manner of things like teacups, dolls, or shoes. The Taft Museum is enjoying the two hundredth birthday of its remarkable building this year, and in this exhibition, seeks to tell the story—or a story, anyway—of Cincinnati art through the succession of owners through whose hands the building passed. It begins with Martin Baum, a significant figure in the advent of German immigration to Cincinnati and environs who caused the house to be built in 1820. It reaches a kind of apogee in the figure of Nicholas Longworth, a lawyer turned real estate investor and winemaker who owned the house for a third of a century starting in 1830, and saw himself, among other things, as a true patron of the arts. The story nods in passing at David Sinton, whose daughter Anna would marry Charles Phelps Taft, which then takes us to the Tafts, whose collection became the core of the Museum bearing their name in 1832.

All in all, the show suggests that cultural receptivity to art—civic ambition—is a fundamental ingredient in developing a climate for the arts, which in turn creates a reputation that will draw young artists to a place like Cincinnati from a several hundred mile radius, the way southern baseball fans used to be drawn to Cincinnati before the Braves moved to Atlanta. It proposes that patronage of individual artists in their formative years is essential in developing natural talent, though the show often suggests at the same time that if there isn’t a steady market for works of art, the individual talents will move on. And it implicitly demonstrates that the arts only become truly self-sustaining when there is a school to train and employ them, to help them develop skills of the eye and hand and allow them to network. An understory of the exhibit is the establishment of an art school that starts as the McMicken School of Design in 1869, initially founded, like the Art Museum, with the pragmatic idea of improving craftsmanship. Within one year of its opening, it had 200 students enrolled. The school initially fulfills its function of civic betterment through producing better laborers in the arts by helping to supply Rookwood Pottery and Strobridge Lithographers with their artisans (Hurley worked for a time at the first and Potthast for a time at the latter). The McMicken School eventually ends up becoming the Art Academy of Cincinnati, with its resounding affirmation of the fine arts. Of the twenty-five or so painters and sculptors in the Taft show who were born after 1850—and thus would have had the option of attending the new art school–almost twenty attended the Art Academy and some seven of them taught there, often for decades. Three of the artists in the exhibition would go on to become the head of the Academy.

The show is not about the Taft Museum’s own collection. There is actually only one work on display from the Taft’s holdings, a portrait bust of Alphonso Taft by Hiram Powers (c. 1870s). Anna and Charles Taft were notoriously uninterested in American paintings in general and still less by Cincinnati artists, of whom they ended up buying only two works, Henry Farny’s “The Song of the Talking Wire” (1904) and Frank Duveneck’s “The Cobbler’s Apprentice” (1877). It’s not clear why they purchased those; one would like to have been a fly on the wall. The Tafts themselves are an afterthought in this particular exhibit, though Duveneck—far more as a teacher than as an artist—is not. “The Splendid Century’s” story is partly one of needing to find the right sort of institution to support the development of the arts. In the end, even the possibility of direct patronage doesn’t hold a candle to a teacher who will attract students from an ever-widening radius.

If Martin Baum hadn’t caused the house on Pike Street to be built, he would barely merit mentioning in the story of the development of art in Cincinnati. As the excellent catalogue essay by Tamera Lenz Muente tells us, he didn’t collect art, offer patronage to young artists, or commission works (that we know of) besides portraits of himself that would only have been seen by his house guests. He seemed to have had a role in the founding of the Western Museum in 1817 (which became, eventually, the Museum of Natural History), but he was an early believer in the potential of Cincinnati—the evidence of which is in the very substantial house he lived in for five short years. He arrived here in 1795 when Cincinnati had perhaps 500 residents; a century after he moved into his house, Cincinnati had grown into the 16th largest city in the country (today, it is the 65th). A work of art the show associates with the Baum years is John James Audubon’s charcoal profile portrait of Barbara Fontaine Cosby Todd, done in 1819, just before he arrived for his brief stay in Cincinnati as an employee of the Western Museum. It is not clear what formal training, if any, Audubon had acquired early in his life, and his portrait of Todd has some of the look of a self-taught artist, though a terrifically talented one: there is a love of linearity even in the portrait’s curves, and equal attention is lavished on her hair and her collar as there is to her eye. A killer baroque curl delicately knots itself at the edge of her eyebrow. Before a full year was out, the Western Museum’s taxidermist on the road again, starting his great work on the birds of America.

John James Audubon, “Barbara Fontaine Cosby Todd”, 1819, charcoal on paper, 9 3/4 x 7 1/2 in. Courtesy of The Filson Historical Society, Louisville, Kentucky

Nicholas Longworth, by contrast, was the real deal for the arts world in mid 19th century Cincinnati. He is the show’s central figure, and some of the air goes out of the exhibition after his sections. Longworth acquired his fortune through a natural aptitude for buying parcels of farmland in places where the growing city was bound to expand. With the money he made, he invested, among other things, in growing grapes on the hillsides of Mt. Adams and, eventually, in thousands of sloping acres between Cincinnati and Ripley which were not very useful for growing anything else. Once he had mastered making sparkling wine from the sweet and sturdy Catawba grape, he ended up selling hundreds of thousands of bottles a year, many to the same sort of people who worked his fields for him: low wage German immigrants. He also turned his fortune to philanthropy, giving small amounts of money directly to the down-and-out while setting aside larger amounts to become a generous, enthusiastic, and erratic patron. He collected art (the Art Museum’s 9’ by 12’ painting of “Ophelia Before the King and Queen” by Benjamin West once hung in his house), commissioned art (including the Taft’s famous Duncanson murals), and paid for the training of such artists as Hiram Powers, Duncanson, and Worthington Whittredge. He opened his house to young painters so that they could study from works in his collection, and helped the struggling artists plan out their careers, a favor that must have sometimes seemed burdensome to them. Artists who left Cincinnati to study with Longworth’s support and guidance–with established artists or at schools on the east coast or in Europe–frequently did not return.

Longworth had an eye for precocious talent. The untutored painter Lilly Martin (later Spencer) came to his attention when she was just a teenager in Marietta. Longworth offered to send her to Boston to study, but she chose instead to come to Cincinnati and study with a local artist (James Henry Beard, who had also turned down Longworth’s offer of east coast study), where she thought, perhaps, there would be a more natural market for her works. We meet Spencer, a wonderful painter entirely new to me, first through an unconventional “Self-Portrait” (c. 1840) in which she is lying on the grass, leaning her cheek on her fist, looking directly and forthrightly out at us. It has a striking mix of formal and informal elements to it, from her carefully chosen jewelry to a long curl that hangs down over one eye. In addition to the usual informative label, this work, along with perhaps a dozen more, has a “More to the Story” label which helps contextualize works in their historical, social, and economic contexts. I found myself looking forward to “More to the Story” labels; this one helps situate Spencer’s art in a century where women would normally be confined to domestic duties, and suggests that women who were gainfully employed were typically unmarried—unlike Spencer, who eventually became the main breadwinner of her family. There was a particularly thoughtful and thought-provoking “More to the Story” label accompanying Elizabeth Nourse’s “Head of a Girl” (c. 1880s); where the main label has sensible biographical and formalist notes about Nourse’s striking sketch, the “More to the Story” label suggested where Nourse might have encountered a young Black girl like the one she painted here, and what sort of education the subject might have been receiving in the segregated school systems of Cincinnati at the time. It certainly crossed my mind that there is more to the story on virtually every object in virtually every museum, but I highly praise the Taft’s decision to help visitors think about art in wider contexts.

Lilly Martin Spencer, “Shake Hands?”, 1854, oil on canvas, 29 1/2 x 24 3/4 in. On loan from the Ohio History Connection, Columbus, Ohio

A second work by Spencer, “Shake Hands?” (1854), depicts a woman in a well-stocked kitchen reaching out a flour-covered hand to offer to shake with the viewer. Gotcha! She laughs heartily at her own joke. It is hard to tell quite who she is. She seems a little too well-dressed to be the cook and a little too unkempt and ruddy-cheeked to be the mistress. By this point in her career, Spencer had clearly seen 17th and 18th century still lifes; take the figure away and there is an elegance to the interplay between things that are shiny and things that are slimy when it comes to food preparation. It is almost as if Spencer imagines what would happen if a plain-spoken, informal American woman were to have been dropped down into a European painting of a century or two earlier, a statement of implicit patriotism.

Portraiture of various sorts is a natural barometer for a developing arts community. James Roy Hopkins’s “Brother and Sister” (c. 1915-17) seemed to me the most remarkable 20th century figurative work in the show. Hopkins painted it as part of his Cumberland Suite, portraits of the people he found in the Cumberland Falls area of Kentucky, about three hours due south of Cincinnati. Hopkins was married to Edna Boies Hopkins, an important maker of color woodcuts, whom he had met when they were both studying at the Art Academy. Together, they spent about a decade in Paris at the start of the 20th century—a great time to have been in a great place—coming home to Cincinnati (and the Art Academy, which he ended up heading after Duveneck’s death) just before the start of World War I. There is an exciting modernity of technique everywhere you look in this picture: the brushwork is loose and expressive, there are broad, flat surfaces, and the two children’s clothes are strikingly patterned. Both young people—since there is little that is childlike about them any more than there is to 16th century portraits of young European princes—are distant and a little melancholy, but there is nothing sentimental about their images. Their clothes look like hand-me-downs—they are too large for them—calling attention to the economics and dynamics of the rest of their family, whom we don’t see. The two figures are not particularly connected to each other, but share expressions that suggest that they have both seen a lot—not much of it good–and have some sense of what they will see in the future.

James Roy Hopkins, “Brother and Sister”, about 1915–18, oil on canvas, 51 1/2 x 32 in. Collection of Annie Bauer and Riley Humler

It is famously hard enough to ponder what is American about American art, but in subtitling the show “Cincinnati Art 1820-1920,” an even harder question is also put into play: What is Cincinnati about Cincinnati art? The earliest landscapes do not give us a helpful answer. Just as many early Hudson River landscapes show the influence of European traditions that see mountains more like Alps than Adirondacks, so early Cincinnati landscapes seem to be shaped by Hudson River traditions, the go-to set of conventions for depicting the American scene. William Louis Sonntag’s “Cincinnati” (1849) has not yet found an idiom proper to our topography—at least, as we see it today. Two men are poling their raft through a miasma-filled shallow backwater overgrown with leafy trees at various stages of their lives. There is an improbably tall distant hill. There is no hint of the majesty of the Ohio River, and the trees seem designed to obscure the flatness of the rest of the landscape as if it were something to be ashamed of. Sonntag would go on to make his reputation as a Hudson River painter in the more congenial world of mountains, cliffs, and distant sparkling rivers. Like Sonntag, Worthington Whittredge received generous help from Longworth, including support for a stay in Europe in the 1840s, but didn’t stay long in Cincinnati upon his return. Anthony Janson has written of Whittredge that when he returned from Europe, he was startled to discover the work of the second generation of Hudson River painters—inspired by Durand rather than Cole—who were more drawn to observation and expressive use of closely observed colors than to high historical drama. Though he did paint a city view of Cincinnati in the 1840s (which is unfortunately not in the show), his peers and his market were in the east. It is something of a lost opportunity—and a reminder, perhaps, of the limitations of even a generous patron like Longworth. I would have loved to have seen what a painter of Whittredge’s skill could have done with the flatter topography of the Midwest, where you cannot rely on mountains for visual interest and pictorial punctuation.

In terms of working to establish a set of visual terms for the landscape of Cincinnati, it is hard not to think about the work of Robert Duncanson, the Black painter whose career was energetically promoted by Nicholas Longworth. Longworth commissioned the restored murals in the entry hall of the Taft Museum (which were apparently never seen by the Tafts, as they’d been covered by wallpaper before the Tafts moved in), and who then underwrote a trip to Europe for Duncanson, in the company of Sonntag. It is hard to do justice to the work and the even more remarkable career of Duncanson in a paragraph or two. But it interested me that neither of the two Duncanson landscapes in the show depict the Cincinnati area, though the CAM has at least two such works. “Landscape with Classical Ruins” (1859) is a fantasia of actual ruins, imaginary ruins, and a dreamy landscape, still much in debt to artists like Cole.

Robert S. Duncanson, “Loch Long”, 1867, oil on canvas 19 1/2 x 33 11/16 in. Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields, Gift of the Alliance of the Indianapolis Museum of Art, 1997.142

“Loch Long” (1867) is a fabulous painting–as good a Duncanson as I’ve seen anywhere–of the Scottish highlands. One wonders what such a scene meant to him. The label suggests that he painted the work under the influence of Sir Walter Scott’s Waverly novels, which retold the stories of the Northern British isles from the Middle Ages almost to Scott’s own time, along with the High romance and socioeconomic changes that accompanied that historical sweep. The “More to the Story” label reminds us that Duncanson left Cincinnati—and eventually the United States—in response to the anti-Black riots that wracked the United States in general and Cincinnati in particular during the Civil War. Though he came back after the war, Duncanson would have found racial attitudes and politics in his adopted city still fraught. I may be disappointed that he did not contribute much to the development of a “look” for the Cincinnati landscape, it is also surely true that his post-Civil War paintings represent a shrewd reading of his audience: in the aftermath of war, the kind of men who bought paintings were looking for depictions of imaginary realms that were so realistic to the eye that you could touch them—a dream world come true. Artist and audience may have been seeking idealized alternatives to the world unfolding around them.

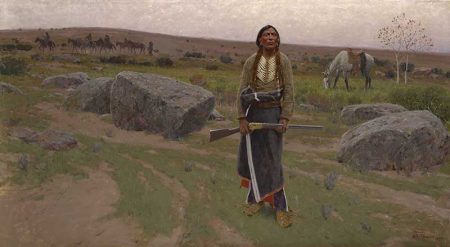

I found the paintings of the American west—specifically, the paintings of Native Americans in western settings—hard to evaluate. They are both handsome and troubling. Henry Farny and Joseph Henry Sharp spent a great deal of time out west, and observed the native people, living for substantial amounts of time among them. Both took their subjects seriously and studied their lives, their objects, and their histories. They were born in the 1840s and 50s—around the time it ceased to be possible to think of Cincinnati as “the west.” Their connections to Cincinnati help suggest that the Queen City was a pretty cosmopolitan place with interests far beyond the Midwest. And yet. Though I think Farny was a highly skilled painter, “Indians Moving Camp” (1898) left me cold. Farny studied in Europe and brought back some of the last vestiges of a Germanic painterly but gloomy realism to an artistic world that was well into post-Impressionism by 1898. Somewhere along the way, Cincinnati had gone from being one of America’s most forward-looking cities in the 1840s to a place where old traditions find comfortable homes. Farny’s central figure—a Native American in full dress, standing alone with a thousand yard stare, separated from the rest of his tribe as they move out, starting the next stage of their nomadic journey—has psychological complexity, but there is something about his noble stoic bleakness that brings to mind the famous Indian with a tear ad from 1971. (The model for that tear seen round the world turned out to be Italian-American and not Indian at all.) It’s like a moment encased in fake amber.

Henry Farny, “Indians Moving Camp”, 1898, oil on canvas, 21 x 39 3/8 in. Loan courtesy of the Eiteljorg Museum of American Indians and Western Art, Indianapolis, Indiana

I do not generally fret about cultural appropriation, but there does seem something colonial about the image. The Taft senses some of this as well; the “More to the Story” tag calls to mind that this was painted eight years after Wounded Knee. Theodore Roosevelt praised and encouraged Farny’s work, but was also capable of saying in 1886: “I don’t go so far as to think that the only good Indians are the dead Indians, but I believe nine out of every 10 are.” The American admiration of Native Americans was a complex stew whose richness—and considerable rancidity—is not well represented by this Farny painting. I have generally thought that Sharp was not as good a painter as Farny, but I found myself much preferring his “Portrait of a Taos Indian Girl” (1920s) to Farny’s “Moving Camp.” Sharp’s painting is more modern in every way. It feels more engaged with the art of its time than Farny’s is, from the striking monotone handling of the adobe wall behind the model to the reticence of the central figure. The painting could not be more traditional in its presentation of an Indian subject, but there is something unsettling and resistant about it as well. Although the tag tells us that she has a name (Crucita) and that Sharp painted her more than 65 times, there is still something admirable to me about the way she is turned away from the artist and the audience. She is not emotionally available to us; she is keeping at least some of her secrets.

There are statues and vases of Indians as well. I have an untutored eye when it comes to Rookwood pottery. I am overlooking Rookwood’s contribution to Cincinnati art, though the curators have not. When it comes to Rookwood, there is always more to the story. It was a training ground for painters, a serious employer of women artists, a story of women’s business acumen, and a magnet that drew in talent and inspiration from all over the world. Nonetheless, to my untrained eye, Rookwood is more often in love with the modes of the past, like Grace Young’s “Vase” (1899), which closely copies a photograph of an Apache woman. Only occasionally does Rookwood seem to me to break free, as it does in Lorinda Epply’s “Vase” (1928) with its abstract “Butterfat” glaze whose white bubbles both reveal and veil a floral design beneath.

It was somewhere around here in the exhibit that things got muddled for me. Just as the quality of the paintings got consistently better, it seemed less clear to me in just what sense we were looking at “Cincinnati Art.” The more the paintings were engaged with the movements and issues of their time, the faster the Cincinnati-based painters got out of Dodge, seldom to return. There is a fine Edward Potthast, “A Family Outing” (c. 1922), which shows the artist working on what he is best known for, painting sun-drenched beaches. In this particular painting, we see people of a range of ages and functions sitting on a park bench not far from the waves: a mother, children of different ages, older people using an umbrella to stay out of the sun. It seems like a conscious decision to leave behind both the topography and the palette of Cincinnati art. The curators have chosen an absolutely stunning John Henry Twachtman painting, “View of the Brush House, Cos Cob, Connecticut” (c. 1901), though I have rarely seen a Twachtman that wasn’t stunning. There was an actual building in Cos Cob called the Brush House; it’s not an allegory of painting, though it could be. The brushwork is astonishing. Though the colors themselves are not that remarkable—Twachtman often preferred a faded and restrained palette—the drawing is everywhere electric. There are curves that leap and dive and squiggles that could suggest underbrush that is both dense and thinning at the same time. Twachtman had a special genius for painting the material world in a way that dematerialized it, memorializing the utter ordinariness of the world around him. There exist a handful or two of paintings that Twachtman did of Cincinnati and environs, and I wish there were more: had he chosen to, he could have seen the Midwest landscape in a transformative way.

John Henry Twachtman, “View of the Brush House, Cos Cob, Connecticut”, about 1901, oil on canvas, 30 1/8 x 30 1/4 in. The Dayton Art Institute, Gift of William P. Patterson, 1988.66

Early in the show is what I would regard as a prophetic painting by Alexander Wyant, “Falls of the Ohio, Louisville” (1863). The catalogue essay tells us that Wyant found his calling when he saw some of the earlier works by George Inness, around the time of Inness’s “The Lackawanna Valley” (1855) which shows a train making its way through a bucolic landscape without disrupting its essential natural harmony. Inness subsequently gave Wyant a letter of introduction to Nicholas Longworth who, as usual, supported the further training on another young artist. The sensibility of early Inness—with its desire to testify to the successful integration of the human and the natural—is very much in evidence in “Falls of the Ohio.” Dominating the foreground is a river cove sheltered by trees where a small family is curiously digging for something. Except that the river is more powerful, the foreground is not that far removed from the vision of Sonntag’s “Cincinnati” a decade and a half earlier. But what a difference those years make! In the background, we see Louisville spreading out as far as the eye can see as a bustling city crammed with housing and industry. The landscape has been engineered to accommodate the railroad—which would change the fortunes of all the Midwest’s river cities in a few short decades—and a train makes its way along the far side of the shore. Towers of smokestacks make it clear that humans have claimed this ground as their own.

Alexander Helwig Wyant, “Falls of the Ohio, Louisville”, 1863, oil on canvas, 40 x 56 in. Collection of the Speed Art Museum, Louisville, Kentucky

This vision is made more modern and brought home to Cincinnati in Lewis Henry Meakin’s remarkable “Clifton, Cincinnati” (c. 1890-95). Painted from somewhere on the grounds of the Robert Bowler estate in what is now Mt. Storm Park, “Clifton” looks out across a wooded ravine towards the sundrenched skyline where the University of Cincinnati and the hospitals are today. As with the Wyant painting, smokestacks are spewing ash and steam into the sky, and there is a clear line of demarcation between the world of nature and the world that man has built up. Unlike the Wyant, in the Meakin nature does not need to be captured tree by tree or ripple by ripple: what matters is the sweep of the hill as the broad abstracted shapes of trees and bushes in the fall lead to the warm-toned, amiable busyness of the vibrant suburb. When this painting was completed, Clifton was enjoying its boom years due to the expansion of the streetcar lines. There is a distant steeple on the skyline, but its presence called attention in my mind to how generally secular the Cincinnati depicted in this show was, though some half dozen steeples might have been visible from Meakin’s vantage point.

Lewis Henry Meakin, “Clifton, Cincinnati”, about 1890–95, oil on canvas, 32 x 42 1/4 in. Collection of Dr. Jim and Lois Sanitato

An exception to that rule of a more or less secular Cincinnati—and another truly exceptional painting—is Edward T. Hurley’s “Mount Adams” (1922), which features a twilight cityscape in the snow dominated by the Church of the Immaculata. The lights are on inside houses we cannot see into—spots of warm set into the winter’s chill–while a few figures are trudging up the hill. A closely related painting, “Midnight Mass” (1911), is owned by the CAM, though in the dozen years between them, Mt. Adams—or the artist’s perspective—has changed: in the earlier work, living spaces are more random and cluttered, less easily divided into streets, and more of the buildings seem to be made of wood rather than brick.

As some people romanticize paintings with Indians, I confess to romanticizing paintings of urbanization. Perhaps we get to choose which forms of the picturesque will move us, which fictions of a more inclusive America inspire us, and allow us to overlook the privileged position of artist and audience in relationship to what is being painted. Where Farny’s “Moving Camp” seems to celebrate an image of America already in the past, Hurley’s seems to look forward to the future. I noticed that it was one of the few paintings in the whole show to explicitly acknowledge how electricity has transformed domestic living spaces. “Mount Adams” captures the complexities of that neighborhood, until the massive gentrification of the past half-century or so, which made things more homogenous as well as many, many times more expensive. In the shadow of a monumental public building are rows of private houses with lines of fences to help demarcate where the snow-covered streets can be found. There are sheds and other out-buildings, and open spaces that I’d like to think mark where Longworth’s vineyards used to grow.

“Mount Adams” captures the sense that Cincinnati is made up a assemblage of small towns gathered around a central city. When I think of the painting as being forward-looking, it is in part because there is something Hopperesque to its urban vision, without the theatrics. The massive Church towers over the scene, but it has no special privilege: its bricks are the same colors as the houses, and its windows are the same incandescent dull yellow tint. People are living their lives inside their houses. There is something unapproachable about them. Inside the houses, there is, as always, more to the story. Hurley’s view celebrates the romance of private ownership, and that we live close together in an assemblage of privacies. Perhaps this is not unlike the Cincinnati of a century later, our Cincinnati.

–Jonathan Kamholtz