The Cincinnati-based Paloozanoire organization dedicates itself to creative collaborations and community health, linking the arts to the pursuit of mental wellness. In 2020, when the ravages of a pandemic combined with the shockwaves of racist violence, the need to support psychological and social wellbeing could hardly be plainer. Paloozanoire’s Black and Brown Faces at the Cincinnati Art Museum features African American artists who address the challenges of 2020, clarifying how that troubled year has intensified preexisting struggles. Whether those struggles include police-community relations, gender inequality, or family illness, the show’s paintings and photographs examine how such issues intersect with and intensify each other rather than existing in isolation.

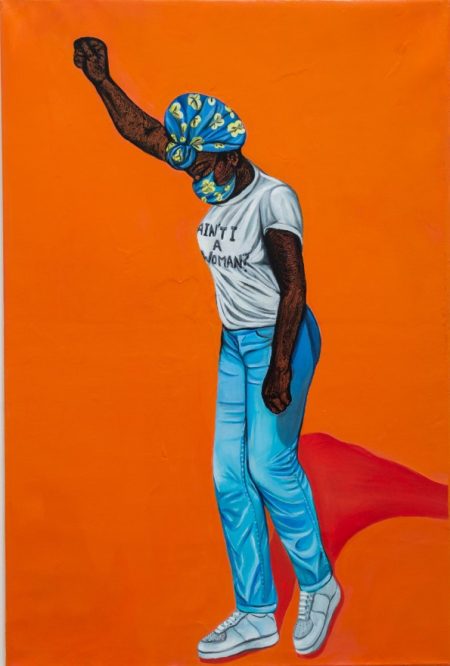

Tired (2020)

Daryl Mintia Daniels

Daryl Mintia Daniels depicts the intersection of racism and gender violence with her painting Tired. It focuses on an African American figure in mid-step, slightly bowed but moving forward, raising a fist to the sky. Her t-shirt reads “Ain’t I a Woman?” She wears a head covering that further evokes Sojourner Truth, along with a nurse’s mask that situates her in the COVID-19 era. A title card next to the work explains that

in 1851 at the Women’s Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio, Sojourner Truth delivered a famous speech that is especially relevant today, during a global pandemic, where an essential EMT worker like Breonna Taylor can be murdered in her own home and the police responsible are only held accountable for endangering her neighbors.

Daniels’s image suggests that struggles from the middle of the nineteenth century continue in 2020, and that even as they take new on forms and nuances, the fight has no less urgency. Facing that urgency on a daily basis proves exhausting; the gradual and maddeningly uncertain character of “progress” tires out the painting’s protagonist. But feeling tired differs from feeling defeated. She raises her fist in solidarity with activists in 2020 and across the preceding centuries. She carries the weight of those years in her body but moves with determination. Daniels accents her face and limbs with electric orange brushstrokes as if to externalize an inner fire—one stoked by the killing of Breonna Taylor, not far from Cincinnati, just months before.

The Door (2020)

Annie Ruth

Annie Ruth similarly conjures that interior fire, offering a similarly fierce rendering of Black women’s historical resolve with her painting The Door. Seeing herself as a “community mama,” Ruth gives us a self-portrait that is simultaneously a picture of collective identity. There is not one face but three, at once distinct and merging, overflowing the borders between the picture plane and surrounding matte. The Door accentuates the permeability of boundaries, whether between self and society, younger and older generations, race and gender politics, surrealism and expressionism. In an interview about the piece, Ruth describes the process of pouring herself onto the canvas, asking viewers to consider the faces as, among other things, a portrayal of complex psychology. She is a community mama in a time of racial upheaval, and she is a painter-poet in a world that too often devalues these arts. She is also a loving daughter whose mother struggles with cancer, and whose art provides a means of coping with the pain. Yet as The Door embodies an attempt at healing, it also validates the varied and unpredictable effects of art on its viewers. The experience of art, as Ruth understands it, involves an overlapping or merging of selves with diverse histories and influences, and in so many combinations we can only dimly anticipate the outcomes.

Arrest the cops that killed (insert name) (2020)

Kevin J. Watkins

The photographs evoke a long history of protest images, alluding to John Dominis’s photo of Black Power at the 1968 Olympics, as well as Jeff Widener’s iconic rendering of “Tank Man” in 1989 Tiananmen Square. Both instances of intertextuality signal uncommon bravery; both suggest human vulnerability in the face of implacable machines. At the center of the collage hangs a portrait of Cincinnati police chief Eliot Isaac, an African American officer caught amid the volatile discourses of racial identity and law enforcement in the city. Watkins offers no clear way to resolve the tension, but he insists on confronting it. And in an interview during the show’s opening weekend, he pleads for the pursuit of truth by means of visual media, even as the “post-truth” regime turns those media to its own ends.

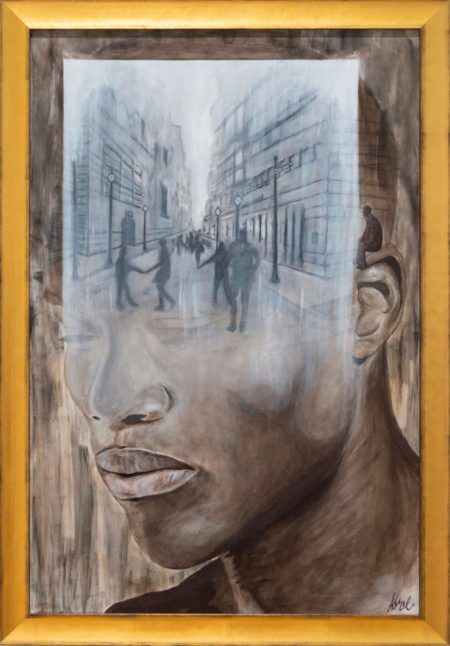

Capture the Awakening (2020)

Adonte Clark

The destabilization of truth has proceeded alongside the erosion of dialogue: as groups consult radically opposed media for news, adopting different standards for what counts as evidence, the possibility for productive interchange shrinks. Nevertheless, Adonte Clark makes a call for wide-ranging conversation and cross-cultural respect in a world intent on shutting those things down. In Capture the Awakening, he aims to spark a particular conversation around the Coronavirus, addressing the ways it drains civic energy by limiting physical closeness. The piece comes out of a series of “abstract expressions” where individual faces blossom into landscapes and city scenes, as though the body were morphing into its own fantasy.

The particular face in Capture the Awakening has a pensive, mournful cast. As its jawline rises into a downtown gathering, we notice a figure perched on the ear, witnessing the assembly from just outside a transparent screen. In the kind of space so often marked by outrage and violence in 2020, the watcher instead sees low-key festival, people holding hands and moving to embrace, blurring into each other rather than keeping a fearful distance. This blurring recalls the social self that Annie Ruth conceptualizes in The Door, but it also connotes a longing for bodily nearness, for expressions of tenderness and friendship that have fallen away during the pandemic. The “awakening” of the painting’s title recognizes the nourishing character of those expressions, teaching us to appreciate the intimacies we take for granted. But the awakening also anticipates a post-COVID return to closeness, a prospect that by late 2020 still feels painfully distant.

Nearby pieces match Clark’s emphasis on coming to consciousness in a time of social malaise. Michael Coppage counsels us to be “awake enough” to spot lies about judicial fairness and equal economic opportunity; Mark Anthony Brown encourages audiences to be alert to the prejudices that limit Black access to galleries, whether as artists or subjects. Jonesy examines how those prejudices often impose restrictions on Black and queer people, while Gee Horton shows how corporate-capitalism intrudes on young people’s processes of maturation. Amid these expressions of critique, Terence Hammonds offers images of African American joy, so vast and vigorous that it lifts into the heavens.

Black and Brown Faces thus exhibits collective will and composure in the face of relentless assault. Paloozanoire celebrates community mothers and fearless activists staring down brutal machines, conjuring an inner fire in a world that conspires to limit Black and Brown voices and votes. When Annie Ruth speaks of pouring the self onto the canvas, she invokes a self that is multiple and widely distributed, one that carries the struggle for communal wellbeing across hundreds of years, pursuing a form of mental health that is inseparable from social justice.

–Christopher Carter